Political assassination opened way to creation of Roman Republic

|

| A magazine illustration depicting the murder of Pellegrino Rossi at the Palazzo della Cancelleria |

The event precipitated turmoil in Rome and led eventually to the formation of the short-lived Roman Republic.

Rossi was the Minister of the Interior in the government of Pope Pius IX and as such was responsible for a programme of unpopular reforms, underpinned by his conservative liberal stance, which gave only the well-off the right to vote and did nothing to address the economic and social disruption created by industrialisation.

Street violence, stirred up by secret societies such as Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy movement, had been going on for weeks in Rome and Rossi had been declared an enemy of the people in meetings as far away as Turin and Florence.

|

| Rossi's reforms had failed to address the social and economic problems besetting Rome |

On November 15, 1848, Rossi arrived at the Palazzo della Cancelleria to present his plan for a new constitutional order to the legislative assembly. He was warned ahead of the meeting that an attempt would be made on his life but he defied the threat with the words: “I defend the cause of the pope, and the cause of the pope is the cause of God. I must and will go.”

However, as he climbed the stairs leading to the assembly hall, an individual stepped forward and struck him with a cane. Rossi turned towards his attacker and as he did so was set upon by another assailant, who drove a dagger into his neck.

The murderer was said to be Luigi Brunetti, the elder son of Angelo Brunetti, a fervent democrat, acting on the instigation of Pietro Sterbini, a journalist and revolutionary who was a friend of Mazzini. Though members of the Civic Guard were in the courtyard when the attack took place, no one attempted to arrest the count’s killer and when crowds gathered later at the house of Rossi's widow, they chanted ‘Blessed is the hand that stabbed Rossi’.

|

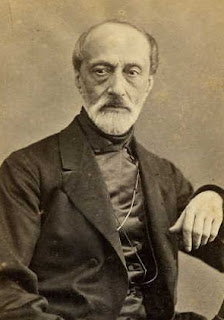

| Giuseppe Mazzini was one of the leaders of the Roman Republic |

Demands were made for a democratic government, social reforms and a declaration of war against the Empire of Austria. Pius IX had little option but to appoint a liberal ministry, but he refused to abdicate and forbade the government to pass any laws in his name.

In the event, on the evening of November 24, with the help of close allies and his personal attendant, Pius IX escaped from the Palazzo del Quirinale disguised as an ordinary priest, slipping through one of the gates of the city and boarding a carriage that was to take him to Gaeta, a city 120km (75 miles) south of Rome, where the King of the Two Sicilies had promised him a refuge.

|

| Rossi was commemorated with a statue in his native Carrara in Tuscany |

The republic put forward some progressive ideas, including religious tolerance and an end to capital punishment, but in the event it was a short-lived revolution. Ironically, it was crushed by a former ally, Napoleon III of France, who had once participated in an uprising against the Papal States but who now, under pressure from the Catholic Church in France, felt compelled to send an army to restore Pius XI to power.

The Romans put up a fight, aided by a Republican army led by Garibaldi, but the city fell in late June and with it the Republic.

| The Palazzo della Cancelleria, built between 1489 and 1513, is thought to be the oldest Renaissance palace in Rome |

Travel tip:

The Palazzo della Cancelleria, which is situated between Corso Vittorio Emanuele II and the Campo de' Fiori, is a Renaissance palace, probably the earliest Renaissance palace to be built in Rome. It is the work of the architect Donato Bramante between 1489 and 1513, initially as a residence for Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who was the Camerlengo - treasurer - of the Holy Roman Church under Pope Sixtus V. It evolved as the seat of the Chancellery of the Papal States. The Roman Republic used it as their parliament building.

The Palazzo della Cancelleria, which is situated between Corso Vittorio Emanuele II and the Campo de' Fiori, is a Renaissance palace, probably the earliest Renaissance palace to be built in Rome. It is the work of the architect Donato Bramante between 1489 and 1513, initially as a residence for Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who was the Camerlengo - treasurer - of the Holy Roman Church under Pope Sixtus V. It evolved as the seat of the Chancellery of the Papal States. The Roman Republic used it as their parliament building.

Rome hotels by Booking.com

Travel tip:

The Palazzo del Quirinale was built in 1583 by Pope Gregory XIII as a summer residence and served both as a papal residence and the offices responsible for the civil government of the Papal States until 1870. When, in 1871, Rome became the capital of the new Kingdom of Italy, the palace became the official residence of the kings of Italy, although some monarchs, notably King Victor Emmanuel III (1900–1946), lived in a private residence elsewhere. When the monarchy was abolished in 1946, the Palazzo del Quirinale became the official residence and workplace for the presidents of the Italian Republic. So far, it has housed 30 popes, four kings and 12 presidents.

|

| The Palazzo del Quirinale has been the residence in Rome of 30 popes, four kings and 12 presidents |

The Palazzo del Quirinale was built in 1583 by Pope Gregory XIII as a summer residence and served both as a papal residence and the offices responsible for the civil government of the Papal States until 1870. When, in 1871, Rome became the capital of the new Kingdom of Italy, the palace became the official residence of the kings of Italy, although some monarchs, notably King Victor Emmanuel III (1900–1946), lived in a private residence elsewhere. When the monarchy was abolished in 1946, the Palazzo del Quirinale became the official residence and workplace for the presidents of the Italian Republic. So far, it has housed 30 popes, four kings and 12 presidents.

Stay in Rome with Booking.com

More reading:

Why Mazzini was seen as the hero of the Risorgimento

Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand

How Aurelio Saffi became Mazzini's trusted ally

Also on this day:

1905: The birth of band leader Mantovani

1922: The birth of neorealist film director Francesco Rosi

1940: The birth of fashion designer Roberto Cavalli

Home

More reading:

Why Mazzini was seen as the hero of the Risorgimento

Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand

How Aurelio Saffi became Mazzini's trusted ally

Also on this day:

1905: The birth of band leader Mantovani

1922: The birth of neorealist film director Francesco Rosi

1940: The birth of fashion designer Roberto Cavalli

Home