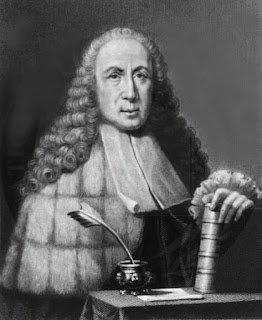

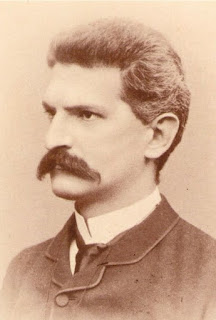

Revolutionary who became Prime Minister

|

| Alessandro Fortis was Italy's prime minister from 1905 to 1906 |

Fortis led the government from March 1905 to February 1906. A republican follower of Giuseppe Mazzini and a volunteer in the army of Giuseppe Garibaldi, he was politically of the Historical Left but in time managed to alienate both sides of the divide with his policies.

He attracted the harshest criticism for his decision to nationalise the railways, one of his personal political goals, which was naturally opposed by the conservatives on the Right but simultaneously upset his erstwhile supporters on the Left, because the move had the effect of heading off a strike by rail workers. By placing the network in state control, Fortis turned all railway employees into civil servants, who were not allowed to strike under the law.

Some politicians also felt the compensation given to the private companies who previously ran the railways was far too generous and suspected Fortis of corruption.

His foreign policies, meanwhile, upset politicians and voters on both sides. His decision to join a Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary was particularly unpopular.

His downfall came with a commercial treaty negotiated with Spain, which included a reduction in duties on the importation of Spanish wines. This was seen to be a threat to the livelihood of Piedmontese and Apulian viticulturists and led to a defeat in the Chamber of Deputies, prompting Fortis to resign.

|

| A scene from the Battle of Mentana, part of the 1867 assault on Rome in which Fortis fought under Garibaldi |

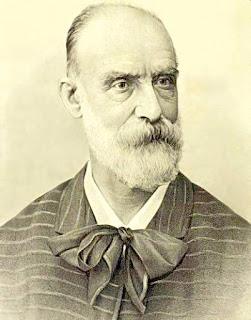

He attended the University of Pisa, where he studied law. There his friendship with Sidney Sonnino, who would succeed him as prime minister, strengthened his nationalist convictions.

As a Garibaldino - the name given to Garibaldi’s volunteers - he also went to France in 1870 to fight in support of the Third French Republic.

|

| Fortis became friends with future prime minister Sidney Sonnino at university |

Afterwards, Fortis became more moderate politically, encouraged by the fall of the Historical Right as the controlling block in Italy’s parliament in 1876, and the advent of the Left under Agostino Depretis. Saffi and Fortis were among those who, having previously stood back, now decided to take part in the elections, sensing a change of the Italian ruling class.

After being elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1880, Fortis served as a minister in the first government of Luigi Pelloux between 1898 and 1899 before resigning, disillusioned with the repressive measures introduced under Pelloux to restrict political activity and free speech. He switched his allegiance to the Liberal opposition leader Giovanni Giolitti.

In March 1905 on the recommendation of Giolitti, he formed his first government. The nationalization of the railways was one of his first major policy decisions.

He gained some credit after introducing a special law to help the victims of the 1905 Calabria earthquake but he was already unpopular and his government was defeated in December 1905 over the trade treaty with Spain. He definitively resigned two months later after his attempt to form a new government failed. He died in Rome in December 1909.

|

| Piazza Aurelio Saffi is the main square in Forlì |

With a population of almost 120,000, Forlì is a prosperous agricultural and industrial city. A settlement since the Romans were there in around 188BC, the city has several buildings of architectural, artistic and historical significance. Forlì has a beautiful central square, Piazza Aurelio Saffi, which is named after Aurelio Saffi, who is seen as a hero for his role in the Risorgimento. Other attractions include the 12th century Abbey of San Mercuriale and the Rocca di Ravaldino, the strategic fortress built by Girolamo Riario and sometimes known as the Rocca di Caterina Sforza.

|

| The town of Bagolino sits in the Caffaro valley in the northern part of Lombardy |

The Battle of Monte Suello took place close to Bagolino, a small town in northern Lombardy, close to the border with Trentino, about 35km (22 miles) north of Brescia. Bagolino, whose location in the valley of the Caffaro river has been strategically important in several conflicts in history, has a well-preserved medieval centre with narrow streets, porticoes and steep staircases. The area produces a cheese called Bagòss, which is similar to Grana Padano and Parmigiano in its salty taste and hard texture, but is different in that it is subtly flavoured with saffron.

More reading:

Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand

Giuseppe Mazzini - hero of the Risorgimento

How Aurelio Saffi defied a 20-year jail sentence to become part of the first government of the unified Italy

Also on this day:

1797: The birth of Sir Anthony Panizzi - revolutionary who became Principal Librarian at the British Museum

2005: Camorra boss Paolo di Lauro captured in Naples swoop

Home