Fisherman who led Naples revolt

The 17th century insurgent known as Masaniello was born on this day in 1620 in Naples.

Onofrio Palumbo's portrait of Masaniello,

which is in San Martino museum in Naples

A humble fishmonger’s son, Masaniello was the unlikely leader of a revolt against the Spanish rulers of his home city in 1647, which was successful in that it led to the formation of a Neapolitan Republic, even though Spain regained control within less than a year.

The uprising, which followed years of oppression and discontent among the 300,000 inhabitants of Naples, was sparked by the imposition of taxes on fruit and other basic provisions, hitting the poor particularly hard.

Masaniello - real name Tommaso Aniello - was a charismatic character, well known among the traders of Piazza Mercato, the expansive square that had been a centre of commerce in the city since the 14th century.

Born in a house in Vico Rotto al Mercato, one of the many narrow streets around the market square, situated close to the city’s main port area, he followed his father, Ciccio d’Amalfi, into the fish trading business.

He had his own clients among the Spanish nobility, with whom he traded directly to avoid taxation. He was a smuggler, too, although he was frequently caught. He took his regular spells in prison on the chin but was less phlegmatic when his young wife, Bernardina, was arrested and sentenced to eight days in jail, after she had entered the city with a quantity of flour - also subject to tax - hidden in a sock.

Masaniello was told he could spare Bernardina from the ordeal of prison if he paid the authorities a ransom of one hundred crowns. He found the money, but only by putting himself in debt, after which he resolved that he would somehow avenge the Neapolitan people against their oppressors.

The opportunity arose after one of his own stays in prison, in which he met a lawyer, Marco Vitale, through whom he came into contact with several members of the Naples middle classes who wanted to see something done about the corruption among the tax inspectors and the privileges granted to the nobility.

An illustration of Masaniello (right)

with academic Giulio Genoino

Among them was an octogenarian cleric and academic, Giulio Genoino, who recognised in Masaniello someone who could command popular support and recruited him to his cause.

It was under Genoina’s instruction that Masaniello organised a demonstration on 7 July, 1647, among the fruit sellers of Piazza Mercato, having persuaded two of his relatives to refuse to pay the tax on fruit imposed by a new viceroy, Rodrigo Ponce de León, Duke of Arcos, who had arrived in Naples the previous year with a brief to raise money for the faltering Spanish Habsburg empire.

The demonstrators were aware that there had been an uprising against the Spanish rulers in Sicily a couple of months earlier and their protests quickly turned into a riot. Genoino tried to restore order, having envisaged a longer campaign of insurgency, but Masaniello had his own motives. He led a mob numbering nearly a thousand on a rampage, ransacking the armouries and opening the prisons.

|

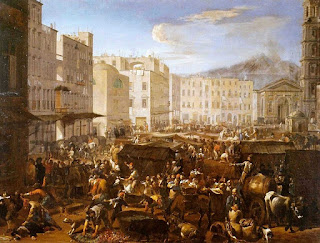

| The Roman painter Michelangelo Cerquozzi's painting of the revolt in Piazza del Mercato |

De León acceded but the Naples nobility were unhappy. Even before the ceremony to confirm his elevation to Captain-General, Masaniello was the target of an assassination attempt. Little more than a week after the riots in Piazza del Mercato, Masaniello went to the Basilica Santuario di Maria Santissima del Carmine, a church on the edge of the square.

He interrupted mass and delivered a blasphemous address denouncing his fellow-citizens. Arrested, he was taken to a nearby monastery and executed, after which his head was paraded on a pike around the streets of Naples.

The death of Masaniello did not restore order. Extremists took over and a second revolution took place in August which culminated in the proclamation of a Neapolitan republic under French protection.

The Spanish fleet attempted to regain control, bombarding the city in October 1647 but failed to break the resolve of the insurgents and Naples was declared a free republic. However, rival factions among the revolutionaries could not agree on a way forward and in April 1648 the Spanish regained control of the city.

Travel tip:

The Fountain of the Lions in Piazza Mercato looking

towards the Chiesa di Santa Croce e Purgatorio

Piazza Mercato in Naples has long been the focal point of commercial life in the city due to its location not far from the port. Overlooked by the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine, it was the setting for the execution of Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel and her fellow revolutionaries in 1799. It was also the location for the beheading in 1268 of Corradino, a 16-year-old King of Naples. Michelangelo Cerquozzi, the Baroque painter born in Rome in 1602, collaborated with the painter Viviano Codazzi in 1648 on a canvas depicting the Revolt of Masaniello, which is currently at the Galleria Spada in Rome.

Travel tip:

The Basilica of Santa Maria del

Carmine overlooks the square

The Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine can be found at one end of Piazza Mercato. Its history goes back to the 13th century, when it was established by Carmelite friars driven from the Holy Land in the Crusades, who probably arrived in the Bay of Naples aboard Amalfitan ships. Some sources, however, place the original refugees from Mount Carmel as early as the eighth century. The church is still in use and the 75m (246ft) bell tower is visible from a distance, while the square adjacent to the church was the site in 1268 of the execution of Conradin, the last Hohenstaufen heir to the throne of the kingdom of Naples, at the hands of Charles I of Anjou, thus beginning the Angevin reign of the kingdom.

Also on this day:

1844: The birth of photographer and catering entrepreneur Federico Peliti

1861: The death of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning

1925: The birth of politician Giorgio Napolitano

1929: The birth of journalist Oriana Fallaci