Research led to major breakthrough in knowledge of cancer

|

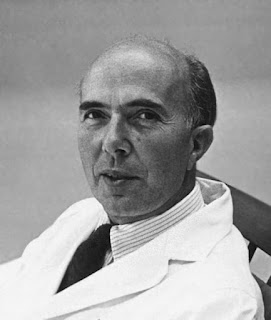

| Renato Dulbecco emigrated to the United States 1946 after studying at the University of Turin |

Through a series of experiments that began in the late 1950s after he had emigrated to the United States, Dulbecco and two colleagues showed that certain viruses could insert their own genes into infected cells and trigger uncontrolled cell growth, a hallmark of cancer.

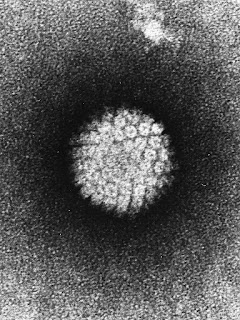

Their findings transformed the course of cancer research, laying the groundwork for the linking of several viruses to human cancers, including the human papilloma virus, which is responsible for most cervical cancers.

The discovery also provided the first tangible evidence that cancer was caused by genetic mutations, a breakthrough that changed the way scientists thought about cancer and the effects of carcinogens such as tobacco smoke.

Dulbecco, who shared the Nobel Prize with California Institute of Technology (Caltech) colleagues Howard Temin and David Baltimore, then examined how viruses use DNA to store their genetic information and, in his studies of breast cancer, pioneered a technique for identifying cancer cells by the proteins present on their surface.

|

| Dulbecco found that viruses such as the human papilloma virus could cause cell mutations |

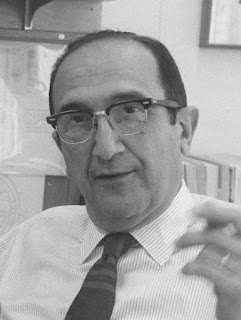

The son of a civil engineer, Dulbecco grew up in Liguria after his family moved from Catanzaro to the coastal city of Imperia. He graduated from high school at 16 and went on to the University of Turin, receiving his medical degree in 1936. He became friends there with two other future Nobel prizewinners, Rita Levi-Montalcini and Salvador Luria, who were fellow students.

Immediately upon graduating, he was required to do two years’ military service. He was discharged in 1938 but soon afterwards called up again as Italy entered the Second World War, joining the Italian Army as a medical officer.

His role eventually took him to the Russian front, where he suffered an injury to his shoulder that meant he was sent back to Italy to recuperate. Disillusioned with Mussolini and horrified at learning of the fate of Jews under Hitler, he decided not to return to the Army, joining the resistance instead. He stationed himself in a remote village outside Turin, tending to injured partisans.

After the war, he was briefly involved with politics, firstly on the Committee for National Liberation in Turin and then on the city council, but soon returned to Turin University to study physics and conduct biological research.

|

| Dulbecco's fellow Turin University graduate Salvador Duria also moved to America |

Dulbecco worked with Dr. Marguerite Vogt on a method of determining the amount of polio virus present in cell culture, a step that was vital in the development of polio vaccine, before becoming intrigued by a thesis written by Howard Temin on the connection between viruses and cancer.

He left Caltech in 1962 to move to the Salk Institute, a polio research facility in San Diego, and then in 1972 to the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now Cancer Research UK) in London.

There was a mixed reaction in Italy when it was learned that ‘their’ Nobel Prize winner had become an American citizen. In fact, his Italian citizenship was revoked, although when he moved back to Italy in 1993 to spend four years as president of the Institute of Biomedical Technologies at National Council of Research in Milan he was made an honorary citizen.

Married twice, with three children, Dulbecco died in La Jolla, California, in 2012, three days before what would have been his 98th birthday.

|

| From its elevated position, Catanzaro has views towards the Ionian Sea and the resort of Catanzaro Lido |

Occupying a position 300m (980ft) above the Gulf of Squillace, Catanzaro is known as the City of the Two Seas because, from some vantage points, it is possible to see the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north of the long peninsula occupied by Calabria as well as the Ionian Sea to the south. The historic centre, which sits at the highest point of the city, includes a 16th century cathedral built on the site of a 12th century Norman cathedral which, despite being virtually destroyed by bombing in 1943, has been impressively restored. The city is about 15km (9 miles) from Catanzaro Lido, which has a long white beach typical of the Gulf of Squillace.

|

| The waterfront of the Ligurian port city of Imperia, with the Basilica of San Maurizio on top of the hill |

The beautiful city of Imperia, on Liguria's Riviera Poniente about 120km (75 miles) west of Genoa and 60km (37 miles) from the border with France, came into being in 1923 when the neighbouring ports of Porto Maurizio and Oneglia, either side of the Impero river, were merged along with several surrounding villages to form one conurbation. Oneglia, once the property of the Doria family in the 13th century, has become well known for cultivating flowers and olives. Porto Maurizio, originally a Roman settlement called Portus Maurici, has a classical cathedral dedicated to San Maurizio, which was built by Gaetano Cantoni and completed in the early 19th century.

Stay in Imperia with Booking.com

More reading:

How Salvador Luria reached the United States after fleeing Paris on a bicycle

Grazia Deledda - the first Italian woman to win a Nobel Prize

The first physiologist to explain human movement

Also on this day:

More reading:

How Salvador Luria reached the United States after fleeing Paris on a bicycle

Grazia Deledda - the first Italian woman to win a Nobel Prize

The first physiologist to explain human movement

Also on this day:

1876: The birth of opera singer and director Giovanni Zenatello

1905: The birth of industrialist Enrico Piaggio

1921: The birth of actress Giulietta Masina

1990: The death of Autogrill pioneer Mario Pavesi

(Picture credits: Catanzaro view by Salvatore Migliari; Imperia waterfront by BMK)

1905: The birth of industrialist Enrico Piaggio

1921: The birth of actress Giulietta Masina

1990: The death of Autogrill pioneer Mario Pavesi

(Picture credits: Catanzaro view by Salvatore Migliari; Imperia waterfront by BMK)