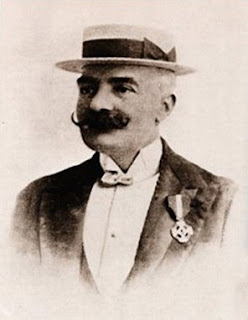

Singer whose style was called the epitome of Italian vocal art

|

| Carlo Bergonzi made his professional opera debut in the role of Figaro in Rossini's The Barber of Seville |

He specialised in singing roles from the operas of Giuseppe Verdi, helping to revive some of the composer’s lesser-known works.

Between the 1950s and 1980s he sang more than 300 times with the Metropolitan Opera of New York and the New York Times, in its obituary, described his voice as ‘an instrument of velvety beauty and nearly unrivalled subtlety’.

Bergonzi was born in Polesine Parmense near Parma in Emilia-Romagna in 1924. He claimed to have seen his first opera, Verdi’s Il Trovatore, at the age of six.

He sang in his local church and soon began to appear in children’s roles in operas in Busseto, a town near where he lived.

|

| Bergonzi spent two years in a prisoner of war camp during World War II |

During World War II, Bergonzi became involved in anti-Fascist activities and was sent to a German prisoner of war camp. After two years he was freed by the Russians and walked 106km (66 miles) to reach an American camp.

On the way he drank unboiled water and contracted typhoid fever. He later recovered, but when he returned to the Arrigo Boito Conservatory after the war he weighed just over 36kg (80lb).

Bergonzi made his professional debut as a baritone in 1948 singing the role of Figaro in Gioachino Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Other baritone parts followed but Bergonzi soon realised the tenor repertoire was more suited to his voice. After retraining he made his debut as a tenor in the title role of Andrea Chenier at the Teatro Petruzzelli in Bari in 1951.

The same year he sang at the Coliseum in Rome in a 50th anniversary concert commemorating Verdi’s death. The Italian radio network RAI engaged Bergonzi for a series of broadcasts of the lesser-known Verdi operas.

|

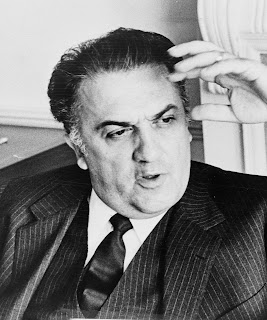

| Carlo Bergonzi and Maria Callas (left) performed together at the Metropolitan Opera |

He made his La Scala debut in 1953 creating the title role in Jacopo Napoli’s opera Mas’Aniello. His London debut came in 1953 and his American debut followed in 1955 in Chicago.

After he appeared at the Metropolitan Opera for the first time the following year he received a glowing review from the New York Times.

He continued to sing at the Met for the next 30 years, appearing opposite such famous sopranos as Maria Callas, Victoria de los Angeles and Leontyne Price. He sang in a performance of Verdi’s Requiem at the Met in 1964 in memory of President John F. Kennedy, under the baton of Georg Solti. His last role at the Met was Rodolofo in Verdi’s Luisa Miller in 1988.

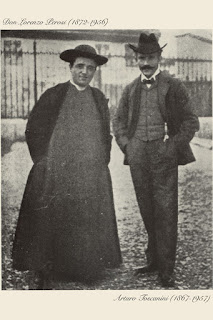

Bergonzi’s chief Italian tenor rivals during his career were Franco Corelli and Mario Del Monaco but he outlasted them both, continuing to sing in concerts into the 1990s.

|

| Franco Corelli's was one of Bergonzi's rivals among Italian operatic tenors |

Sadly, Bergonzi was unable to finish the performance because his voice had been affected by the air conditioning in his dressing room and a substitute tenor had to sing in his place.

After retiring, Bergonzi mentored many famous tenors and the soprano, Frances Ginsberg, was also one of his pupils.

Bergonzi died 12 days after his 90th birthday in Milan, leaving a widow and two sons. He was laid to rest in the Vidalenzo Cemetery, not far from Polisene Parmense.

He left a legacy of beautiful recordings of individual arias and complete operas, including works by Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Pietro Mascagni and Ruggero Leoncavallo.

|

| The church of the Beata Vergine di Loreto |

The village of Polisene Parmense, where Bergonzi was born, is about 40km (25 miles) northwest of Parma and around 20km (12 miles) south of Cremona. In January 2016 it merged with Zibello to form the new municipality of Polesine Zibello. The village contains two buildings of interest - the church of the Beata Vergine di Loreto, also known as Madonnina del Po, which was built between 1846 and 1920 to preserve an effigy fresco of Our Lady of Loreto that had been discovered in an ancient shrine, and the nearby Antica Corte Pallavicina, a fortress that dates back to the 13th century.

|

| The entrance to Bergonzi's restaurant in Busseto, I due Foscari |

Busseto, where Bergonzi sang as a child, is a town in the province of Parma, about 40km (25 miles) from the city of Parma. Verdi was born in the nearby village of Le Roncole but moved to Busseto in 1824. Bergonzi owned a house there and after his retirement also opened a restaurant and hotel there, I due Foscari, named after the Verdi opera about court intrigue in Venice. At the time of his death, I due Foscari was still being run by his son, Marco.

More reading:

How Italy mourned the loss of Giuseppe Verdi

Why Franco Corelli was called 'the prince of tenors'

Pietro Mascagni - a reputation built on one brilliant opera

Also on this day:

1467: The Battle of Molinella sees artillery used for the first time in warfare

1654: The birth of baroque musician Agostino Steffani

1883: The birth of Alfredo Casella, the musician who revived interest in Vivaldi

Home

Home