Liberal leanings prevented scholar’s elevation to the papacy

|

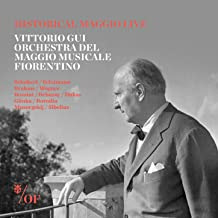

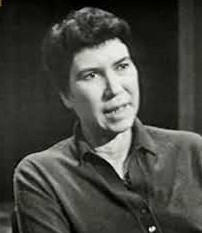

| Carlo Maria Martini, a liberal within the Catholic Church, lost out to papal rival Joseph Ratzinger |

As Cardinal Martini, he was known to be tolerant in areas of sexuality and strong on ecumenism, and he was the leader of the liberal opposition to Pope John Paul II. He published more than 50 books, which sold millions of copies worldwide.

Martini, who expressed views in his lifetime on the need for the Catholic Church to update itself, was a contender for the papacy in the 2005 conclave and, according to Vatican sources at the time, he received more votes than Joseph Ratzinger in the first round.

But Ratzinger, who was considered the more conservative of the candidates, ended up with a higher number of votes in subsequent rounds and was elected Pope Benedict XVI.

Martini had entered the Jesuit order in 1944 when he was 17 and he was ordained at the age of 25, which was considered unusually early.

His doctoral theses, in theology at the Gregorian University and in scripture at the Pontifical Biblical Institute, were thought to be so brilliant that they were immediately published.

After completing his studies, Martini had a successful academic career. He edited scholarly works and became active in the scientific field, publishing articles and books. He had the honour of being the only Catholic member of the ecumenical committee that prepared the new Greek edition of the New Testament. He became dean of the faculty of scripture at the Biblical Institute, was rector from 1969 to 1978, and then rector of the Gregorian University.

|

| In his later years, suffering from Parkinson's disease, Martini moved to Jerusalem |

He started the so-called ‘cathedra of non-believers’ in 1987, an idea he conceived with philosopher Massimo Cacciari. He held a series of public dialogues in Milan with agnostic, or atheist, scientists, and intellectuals about the reasons to believe in God.

He was presented with an honorary doctorate from the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1996 and an award for Social Sciences in 2000. In the same year, Martini was admitted as a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

In 2012, Pope Benedict XVI was considering retirement, but was being urged against it by some of his confidants. By then, Martini was himself suffering from Parkinson’s disease and he encouraged the Pope to go ahead with his decision to retire.

After his own retirement, Martini moved to Jerusalem to continue his work as a biblical scholar.

He died in Gallarate in the province of Varese in 2012. More than 150,000 people passed before his casket in the Duomo di Milano. The Italian Government was represented by Prime Minister Mario Monti and his wife. Martini was buried in a tomb on the left side of the cathedral facing the main altar.

|

| Piazza Umberto I in Orbassano, overlooked by the parish church of San Giovanni Battista |

Orbassano, the comune (municipality) where Martini was born, is about 13km (8 miles) southwest of Turin, falling within the Piedmont capital's municipal area. It can trace its history back to the Roman conquest of Cisalpine Gaul because two imperial era tombstones were found there in the 19th century. The Indian politician, Sonia Gandi, was brought up in Orbassano, although she was born near Vicenza. While studying at Cambridge, Sonia met Rajiv Gandi, who she married in 1968. The couple settled in India and had a family but he was assassinated in his home country in 1991. Orbassano has a pleasant central square, the Piazza Umberto I, the site of the town's two main churches, the parish church of San Giovanni Battista and the Baroque church of the Confraternita dello Spirito Santo, in which the artworks include a Pentecost by Giovanni Andrea Casella from 1647 and a Madonna and saints by Michele Antonio Milocco from 1754.

Book your stay in Orbassano with Booking.com

%2016,%20villa%20Rodolfo%20Mauri%20(Carlo%20Moroni%20con%20Filippo%20Tenconi)%20(2).jpg) |

| Liberty-style villas built by architect Carlo Moroni and his partner, Filippo Tenconi, abound in Gallarate |

Gallarate, where Martini died after he spent his final years living in a Jesuit house, is a small city in the province of Varese, about 42km (26 miles) northwest of Milan. It has a Romanesque church, San Pietro, which dates from the 11th century. In Piazza Garibaldi, where there is a statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi, there is an historic pharmacy, Dahò, where members of the Carbonari used to hide out during the 19th century. Founded by the Gauls and later conquered by the Romans, Gallarate enjoyed prosperity under Visconti control in the 14th and 15th centuries, when the area's textile industry began to develop and grow. By the 19th and 20th centuries, it was an important industrial city, where thousands of workers were employed in Liberty-style factory buildings. The heavy industry has largely gone now, with high-tech businesses a features of the city's modern economy, but the architectural echoes remain. Piazza Garibaldi also features Casa Bellora, a Stile Liberty mansion commissioned by the local captain of industry, Carlo Bellora, who had factories in Gallarate, Somma, Albizzate, and in the Bergamo area, who hired the architect Carlo Moroni to build a house for his family. Moroni and the engineer Filippo Tenconi combined to build numerous villas in what is known as the 'Liberty district' between Corso Sempione and the railway.

Find accommodation in Gallarate with Booking.com

More reading:

How the first railway line in northern Italy sparked 19th century boom

Karol Wojtyla - the first non-Italian pope for 455 years

Carlo Maria Viganò, the controversial archbishop who shocked Catholic Church

Also on this day:

1564: The birth of astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei

1898: The birth of comic actor Totò

1910: The birth of circus clown Charlie Cairoli

1944: Monte Cassino Abbey destroyed in WW2 bombing raid

(Picture credits: Main picture by Mafon1959; older Carlo Martini by RaminusFalcon; Piazza Umberto I by Simoneislanda; via Wikimedia Commons)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)