Rider from Tuscany won Giro d'Italia three times

|

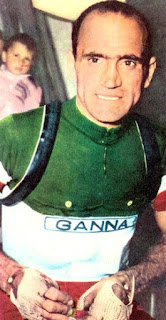

| Fiorenzo Magni |

Tuscan-born Magni was a multiple champion, winning the Giro d'Italia three times, as well as three Italian Road Race Championships. He had seven stage wins in the Tour de France, in which he wore the yellow jersey as race leader for a total of nine days.

His other major victories were in the demanding Tour of Flanders, in which he became only the second non-Belgian winner in 1949 and went on to win three times in a row, a feat yet to be matched.

Magni might have been even more successful had his career not coincided with those of two greats of Italian cycling, the five-times Giro champion Fausto Coppi, who was twice winner of the Tour de France, and Gino Bartali, who won three Giros and one Tour de France.

His reputation for toughness, however, was unrivalled. He relished racing in harsh, wintry weather, as often prevailed in the Tour de Flanders, and refused to give in to injuries if he happened to have a fall.

|

| Fiorenzo Magni finished second in the 1956 Giro d'Italia by using a tyre inner tube gripped in his teeth to steer |

He was taken to hospital but refused a plaster cast and continued the race with his shoulder wrapped in an elastic bandage. Unable to apply force with his left arm, he effectively steered the bike using his teeth, with which he pulled on a piece of rubber inner tube attached to his handlebar.

However, unable to brake with his left hand, he crashed again after hitting a ditch by the road during a descent. This time he broke his left elbow, while the pain from landing on his already broken collarbone caused him to pass out.

Yet even then he refused to retire, screaming for the driver to stop when he regained his senses in the ambulance.

Amazingly he finished second, although his cause had been helped by 60 competitors abandoning the race because of treacherous snow and ice in Trento.

|

| Magni pictured in his army uniform in 1943 |

Controversy haunted his life away from cycling. His wartime service with the Italian Army began with four years based with the 19th Regiment in Florence but in 1944 he was enlisted to the Italian Voluntary Militia for National Security, which was originally the paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party, commonly known as the Blackshirts. Its members had to swear allegiance to Mussolini.

His unit was involved into a violent confrontation with Calenzano partisans in the Apennines, which became known as Battle of Valibona. After the war, identified by a cycling fan among the partisans who claimed Magni stood over him with a gun, he appeared in court, facing a possible 30 years in prison if found guilty of taking part.

In the end he was cleared, testimony from a fellow cyclist supporting his claim to have arrived at the scene of the incident after it had ended. Later, evidence emerged of Magni fighting on the side of the partisans near Monza, but many Italians remained sceptical and his reputation suffered, even at the height of his career in the saddle.

|

| The Church of the Madonna del Ghisallo |

He retained an interest in cycling, helping to establish and maintain a museum and cyclists' chapel at the top of the climb at Madonna del Ghisallo, above Bellagio on Lake Como.

In his later years, he lived in Monticello Brianza, a small community north of Monza, close to the road linking Bergamo with Como in Lombardy. He died there aged 91. His funeral took place at the Duomo in Monza.

|

| The Abbey of San Salvatore at Vaiano |

The town of Vaiano in the northern hills of Tuscany, just above Prato, is notable for the Abbey of San Salvatore, built in the ninth of 10th century, which is at the heart of the medieval village around which the town grew. The bell tower was built in 1258. Vaiano prides itself on its tortelli, a form of stuffed pasta, and holds a Tortello Festival every June.

Travel tip:

The Madonna del Ghisallo, the name given to an apparition of the Virgin Mary the medieval Count Ghisallo claimed saved him when he was being attacked by bandits, became the patroness of cyclists at the suggestion of a local priest after the hill upon which a shrine to the Madonna was built was included in the Giro di Lombardia and later the Giro d'Italia. The Church of the Madonna del Ghisallo honours cyclists who have died in competition and an adjoining museum contains many bikes and shirts worn by riders down the years.

More reading:

The first Giro d'Italia

Attilio Pavesi - Italy's first Olympic road race champion

(Photo of Church of the Madonna del Ghisallo by Marco Bonavoglia CC BY-SA 3.0)

(Photo of Abbey of San Salvatore by Massimilianogalardi CC BY-SA 3.0)

Home