The first botanist to describe the tomato

|

| As a physician, Pietro Andrea Mattioli described the first documented case of cat allergy |

Doctor and naturalist Pietro Andrea Gregorio Mattioli was

born on this day in 1501 in Siena.

As the author of an illustrated work on botany, Mattioli

provided the first documented example of an early variety of tomato that was

being grown and eaten in Europe.

He is also believed to have described the first case of cat

allergy, when one of his patients was so sensitive to cats that if he went into

a room where there was a cat he would react with agitation, sweating and

pallor.

Mattioli received his medical degree at the University of

Padua in 1523 and practised his profession in Siena, Rome, Trento and Gorizia.

He became the personal physician to Ferdinand II, Archduke

of Austria, in Prague and to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, in Vienna.

While working for the imperial court it is believed he

tested the effects of poisonous plants on prisoners, which was a common

practice at the time.

|

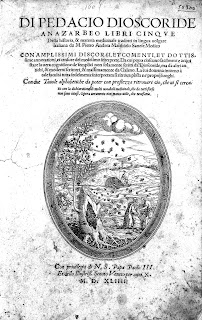

| Mattioli's book about the work of Greek physician Dioscorides |

Mattioli’s interest in botany led him to describe 100 new

plants and document the medical botany of his time in his Discorsi

(Commentaries) on the Materia Medica of Dioscorides, a Greek physician and

botanist. Dioscorides had written a five-volume encyclopaedia about herbal

medicine and other medicinal substances that had been widely read for 1,500

years.

The first edition of Mattioli’s work appeared in 1544 in

Italian. There were several later editions and translations into Latin, French,

Czech and German.

He added descriptions of plants not in the original work and

not of any known medical use. The woodcuts in Mattioli’s work were of a high

standard, helping the reader to identify the plants.

The Scottish botanist Robert Brown later named a plant genus

Matthiola in his honour.

Mattioli died in 1577 during a visit to Trento, now the

capital city of Trentino-Alto Adige.

Mattioli’s birthplace, Siena, is famous for its shell-shaped

Piazza del Campo, where the Palio di Siena takes place twice each year. It was

established in the 13th century as an open marketplace and is now regarded as

one of the finest medieval squares in Europe. The red brick paving, fanning out

from the centre in nine sections, was put down in 1349. The city’s Duomo was

designed and completed between 1215 and 1263 on the site of an earlier

structure. It has a beautiful façade built in Tuscan Romanesque style using

polychrome marble.

Trento is a city on the Adige river, which was formerly part

of Austria-Hungary. It is famous as the location of the Council of Trent in the

16th century, an ecumenical council that led to a Catholic resurgence in the

wake of the Protestant Reformation. It

was annexed by Italy in 1919 and is now one of the country’s most prosperous

cities.

More reading:

Ulisse Aldrovandi - the 'father' of natural history

How Prospero Alpini 'discovered' the coffee-drinking habit that took Italy by storm in the 18th century

Cesare Battisti - the patriot who campaigned for Trentino

Also on this day:

1863: The birth of writer and patriot Gabriele D'Annunzio

1921: The birth of Fiat patriarch Gianni Agnelli

(Picture credit: Piazza del Duomo by Casalmaggiore Provincia via Wikimedia Commons)