Venetian trader who described travels in China

|

| A 19th century portrait in mosaic of Marco Polo at Palazzo Tursi in Genoa |

Accounts of his final days say he had been confined to bed with an illness and that his doctor was concerned on January 8 that he was close to death. Indeed, so worried were those around his bedside that they sent for a local priest to witness his last will and testament, which Polo dictated in the presence of his wife, Donata, and their three daughters, who were appointed executors.

The supposition has been that he died on the same evening. The will document was preserved and is kept by the Biblioteca Marciana, the historic public library of Venice just across the Piazzetta San Marco from St Mark’s Basilica. It shows the date of the witnessing of Polo’s testament as January 9, although it should be noted that under Venetian law at the time, the change of date occurred at sunset rather than midnight.

Confusingly, the document recorded his death as occurring in June 1324 and the witnessing of the will on January 9, 1323. The consensus among historians, however, is that he reached his end in January, 1324.

Born in 1254 - again the specific date is unknown - Marco Polo was best known for his travels to Asia in the company of his father, Niccolò, and his uncle, Maffeo.

Having left Venice in 1271, when Marco was 16 or 17, they are said to have reached China in 1275 and remained there for 17 years. Marco wrote about the trip in a book that was originally titled Book of the Marvels of the World but is today known as The Travels of Marco Polo. It is considered a classic of travel literature.

|

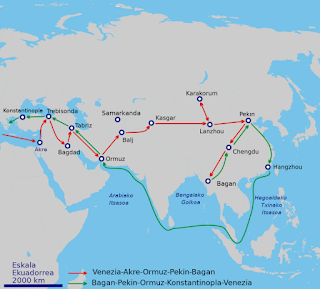

| A map showing the journeys said to have been made by Marco Polo on his travels to China |

The book, which Polo dictated to Rustichello da Pisa, a fellow prisoner of the Genoese who happened to be a writer, introduced European audiences to the mysteries of the Eastern world, including the wealth and sheer size of the Mongol Empire and China, providing descriptions of China, Persia, India, Japan and other Asian cities and countries.

Polo’s father and uncle had traded with the Middle East for many years and had become wealthy in the process. They had visited the western territories of the Mongol Empire on a previous expedition, established strong trading links and visited Shangdu, about 200 miles (320km) north of modern Beijing, where Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty, had an opulent summer palace, and which was immortalised by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge as Xanadu.

Their journey with Marco originally took them to Acre in present-day Israel, where - at the request of Kublai Khan - they secured some holy oil from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. They continued to the Persian port city of Hormuz and thereafter followed overland routes that later became known as the Silk Road.

Travelling through largely rough terrain, the journey to Shangdu took the best part of three years. Marco Polo’s long stay owed itself partly to Kublai Khan taking him into his court and sending him on various official missions. In that capacity, he extended his travels to include what is now the city of Hangzhou and may have crossed the border into India and what is now Myanmar.

|

| A painting of unknown origin of Marco Polo's father and uncle presenting a gift to Kublai Khan |

It was during the second of four wars between Venice and their trading rival Genoa that Marco Polo was captured. He remained a prisoner until 1299, when a peace treaty allowed for his release. Thereafter, he continued his life as a merchant, achieving prosperity, but rarely left Venice or its territories again until his death.

His book, known to Italians under the title Il Milione after Polo’s own nickname, introduced the West to many aspects of Chinese culture and customs and described such things as porcelain, gunpowder, paper money and eyeglasses, which were previously unknown in Europe. Contrary to some stories, his discoveries did not include pasta, which was once held widely to have been imported by Marco Polo but is thought actually to have existed in the Italy of the Etruscans in the 4th century BC.

Christopher Columbus and other explorers are said to have been inspired by Marco Polo to begin their own adventures, Columbus discovering the Americas effectively by accident after setting sail across the Atlantic in the expectation of reaching the eastern coast of Asia.

|

| Marco Polo is buried at the church of San Lorenzo |

One of the wishes Marco Polo expressed on his deathbed was that he be buried in the church of San Lorenzo in the Castello sestiere of Venice, about 850m (930 yards) on foot from Piazza San Marco. The church, whick dates back to the ninth century and was rebuilt in the late 16th century, houses the relics of Saint Paul I of Constantinople as well as Marco Polo’s tomb. Castello is the largest of the six sestieri, stretching east almost from the Rialto Bridge and including the shipyards of Arsenale, once the largest naval complex in Europe, the Giardini della Biennale and the island of Sant’Elena. Unlike its neighbour, San Marco, Castello is a quiet neighbourhood, where tourists can still find deserted squares and empty green spaces.

|

| Arched Byzantine windows thought to have been from the Polo family home |

The Polo family home in Venice, which was largely destroyed in a fire in 1598, was in the Cannaregio sestiere close to where the Teatro Malibran now stands, in Corte Seconda del Milion, one of two small square that recall Marco Polo’s nickname, Il Milione, which may have been coined as a result of his enthusiasm for the wealth he encountered at the court of Kublai Khan in China or as a result of his being from the Polo Emilioni branch of the family. The Byzantine arches visible in Corte Seconda del Milion are thought to have been part of the Polo house. The Teatro Malibran was originally inaugurated in 1678 as the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, opening with the premiere of Carlo Pallavicino's opera Vespasiano. It was renamed Teatro Malibran in 1835 in honour of a famous soprano, Maria Malibran, who was engaged to sing Vincenzo Bellini's La sonnambula there but was so shocked as the crumbling condition of the theatre that she refused her fee, insisting it be put towards the theatre’s upkeep instead.

Also on this day:

1878: The death of Victor Emmanuel II, first King of Italy

1878: Umberto I succeeds Victor Emanuel II

1944: The birth of architect Massimiliano Fuksas

2004: The death of political philosopher Norberto Bobbio

No comments:

Post a Comment