Tuscan was leading figure in Futurist movement

The painter and mosaicist Gino Severini, who was an important figure in the Italian Futurist movement in the early 20th century and is regarded as one of the most progressive of all 20th century Italian artists, was born on this day in 1883 in the hilltop town of Cortona in Tuscany..jpeg)

Gino Severini, typically sporting a monacle, was

an influential figure in 20th century Italian art

He divided his time largely between Rome and Paris, where he died in 1966. Although he was a signatory - along with Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Giacomo Balla - of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurist Painters in 1910, his work was not altogether typical of the movement.

Indeed, ultimately he rejected Futurism, moving on to Cubism, having become friends with Cubist painters Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in Paris, before ultimately turning his interest to Neo-Classicism and the Return to Order movement that followed the First World War.

He attracted criticism among his peers by his associations with the Fascist-supporting Novecento Italiano movement, whose work became closely linked with state propaganda. Severini was involved with Benito Mussolini's "Third Rome" project, supplying murals and mosaics for Fascist architectural structures inspired by imperial Rome.

Working in mosaics became an increasing focus for Severini in his later years, particularly after he rediscovered his Catholic faith. His religious mosaics displayed such refined technique he was dubbed the “father of modern mosaics".

Severini was also the author of many essays and several books on painting, including Du cubism au classicisme (From Cubism to Classicism) in 1921 and The Life of a Painter, a vivid account of his early career.

|

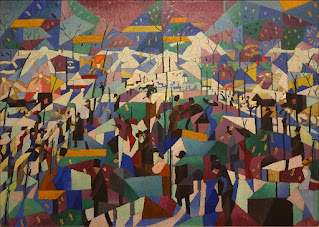

| Severini's Le Boulevard (1913), his Futurist interpretation of Parisian street life |

In 1899, his mother took him to Rome, thinking his prospects would be better there. He gained employment as a shipping clerk. He painted in his spare time and, thanks to the patronage of a fellow Cortonese with whom he had become friends, was able to attend art classes at the Rome Fine Arts Institute, studying nudes. He was not a disciplined student, however, and found himself cut adrift when his frustrated patron cancelled his allowance.

Left to fend for himself when his mother returned to Cortona, Severini was so poor he lived in a room that was essentially a store cupboard in a kitchen in Via Sardegna in Ostiense. In 1900 he met Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla for the first time. Balla took him on as a student, introducing him to the technique of pointillism, a painting method where effects were created by dotting the canvas or other surface with contrasting colours according to the principles of optical science. The technique would have a major influence on Severini's early work and on Futurist painting in general.

|

| Severini (right) with Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carrà, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Umberto Boccioni in Paris in 1912 |

It was through Severini that some of the leading Italian Futurists visited Paris in 1911, absorbing some of Severini’s influence by adopting some of the humanist features of Cubism, namely the human figure in motion, as further means of expressing pictorial dynamism.

Severini’s own Futurist work had been based on human figures, nightclub dancers or simply people in the street, rather than the cars or machines that had been central to the attempts of many of his fellow Futurist artists to depict speed and dynamism in painting. In his nightclub scenes, he would evoke the sensations of movement and sound through rhythmic forms and flickering colours. His Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin (1912) and The Boulevard (1913) were examples of his best work in Paris.

However, Severini did produce some of the finest Futurist war art, notably his Red Cross Train Passing a Village (1914), Italian Lancers at a Gallop (1915) and Armoured Train (1915).

His work over the next few years could be categorised as an idiosyncratic form of Cubism with elements of pointillism and Futurism before he began to experiment with a Neoclassical figurative style in portraits such as Maternity (1916).

|

| Severini's Mosaic of San Marco in his hometown of Cortona |

Only between the wars did Severini begin to find financial stability, realised mainly through his commissions to create frescoes and mosaics.

He produced mosaics for the Palazzo di Giustizia in Milan (1936), the Palazzo delle Poste in Alessandria (1936) and mosaics and frescoes at the University of Padua (1937). He worked for the Mussolini regime at the Foro Italico, a multi-venue sports complex, and the Palazzo degli Uffici, the inaugural building of the EUR project. Severini’s association with the Fascists was roundly condemned within the international artistic community, although none of Severini’s work was overtly pro-Fascist.

After the fall of Mussolini and the end of the Second World War, Severini received lucrative commissions to decorate the offices of the Italian airline companies KLM and Alitalia among other organisations.

His Cubist-inspired Mosaic of San Marco (1961), which adorns the facade of the Church of San Marco in Cortona, is seen as a signature work. He died in Paris in 1966 at the age of 82 but was buried in Cortona.

Travel tip:

Cortona's elevated position gives it commanding

views over the surrounding countryside

Cortona, founded by the Etruscans, is one of the oldest cities in Tuscany. Its Etruscan Academy Museum displays a vast collection of bronze, ceramic and funerary items reflecting the town’s past. The museum also includes an archaeological park that includes city fortifications and stretches of Roman roads. Outside the museum, the houses in Via Janelli are some of the oldest houses still surviving in Italy. Powerful during the mediaeval period, Cortona was defeated by Naples in 1409 and then sold to Florence. Characterised by its steep narrow streets, Cortona’s hilltop location - it has an elevation of 600 metres (2,000 ft) - offers sweeping views of the Valdichiana, including Lago Trasimeno, where Hannibal ambushed the Roman army in 217 BC during the Second Punic War.

Travel tip:

The Piramide Cestia and Porta San Paolo are

two highlights of the Ostiense neighbourhood

Severini’s earliest home in Rome was in the Ostiense neighbourhood, which can be found to the south of the Trastevere district. Bordered by the working class areas of Garbatella and Testaccio, Ostiense itself has shed its own down-at-heel reputation to become an increasingly trendy part of the city, populated by young professionals and boasting a thriving nightlife. The home of the majestic Basilica San Paolo Fuori le Mura - the Basilica of St Paul Outside the Walls - with its gold-plated ceilings, of the Roman Piramide Cestia and the 3rd century Porta San Paolo, the district was built around the Via Ostiense, the ancient road linking the city with the Roman harbour at Ostia.

Also on this day:

1763: The birth of musician Domenico Dragonetti

1794: The birth of opera singer Giovanni Battista Rubini

1906: Vesuvius erupts, killing more than 200 people

1973: The birth of footballer Marco Delvecchio