Calabrian facilitated string of transfers to Italy

|

| Luigi 'Gigi' Peronace is seen by some as football's original players' agent |

Agents are commonplace in football today but they were an almost unknown phenomenon when Peronace set up in business in the 1950s and he is widely accepted as the first of his kind, certainly in terms of building a ‘stable’ of clients.

The charismatic Peronace’s ability to charm all parties in transfer deals - buyer, seller and player - led to him becoming an influential figure in football in both Italy and the United Kingdom over a 25-year period.

Charles, the Welsh giant whose talents persuaded Juventus to almost double the British transfer fee record when they paid Leeds United £65,000 for his services in 1957, remains Peronace’s most famous deal, although he was instrumental in introducing other big-name British players to the Italian game, including the prolific Chelsea and England striker Jimmy Greaves and Scotland’s Denis Law.

Peronace’s first taste of football was as a player in the 1940s with the Calabrian team Reggina, for whom he kept goal despite being quite a small man. Evidence of his skills as a Mr Fixit were emerging even then, as a teenager, when he arranged football matches between English and Australian soldiers and local Calabrian teams.

After the end of the Second World War, Peronace moved to Turin to study engineering. Already with good English, he took a job with Juventus, who needed an interpreter to help their new Scottish coach, William Chalmers. When Chalmers was dismissed after one season, the Turin club hired an Englishman, Jesse Carver, to look after the team.

.jpg) |

| John Charles, who joined Juventus from Leeds United in 1957 |

Intrigued, as soon as his time at Lazio had ended Peronace travelled to England to see Charles in person, contacted the Juventus president Umberto Agnelli and persuaded the Turin club that they should spend whatever it took to sign him.

It took Peronace two years to convince Leeds to sell and Charles to move, but in August 1957, the deal was done. It made headlines, of course, not just for the size of transfer fee but for what the player himself was offered. Juventus gave him an apartment for his family, a Fiat car and a £10,000 signing-on fee - this at a time when the signing-on fee for players moving between English clubs could be as little as £10.

The Charles deal was not Peronace’s first. While wooing Charles and Leeds, he had arranged for South African-born Eddie Firmani, who had Italian heritage, to join Sampdoria from Charlton Athletic. But it was the Charles transfer that gave him credibility.

The Welshman would go on to score 108 goals in 155 matches for Juventus, helping them win the scudetto - the colloquial name for the Serie A trophy - three times and the domestic cup competition, the Coppa Italia, twice.

Peronace helped Charles settle in Turin but in 1961 he returned to England, moved into a plush apartment in Knightsbridge and from there pulled off more headline-making deals. He helped Aston Villa’s Gerry Hitchens move to Inter-Milan, persuaded AC Milan to sign Jimmy Greaves, and Torino to take both Denis Law and the English-born, Scottish-raised striker Joe Baker.

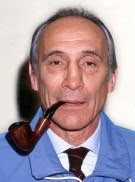

|

| Peronace's close friend, the pipe-smoking Enzo Bearzot |

Always immaculately dressed in the most expensive Italian clothes, Peronace’s natural charm enabled him to befriend the most powerful figures in both English and Italian football, which opened doors in both countries. This was especially useful to him after the abolition of English maximum wage lessened the attraction to players of moving abroad.

A close friend of Sir Denis Follows, the secretary of the English Football Association, he used his contacts to help establish the Anglo-Italian Cup competition.

In Italy, he became a close friend of Enzo Bearzot and worked with him for the Italian Football Federation at the 1978 World Cup in Argentina.

Peronace would doubtless have been alongside Bearzot when Italy’s pipe-smoking coach guided the azzurri to their World Cup triumph in Spain 1982 had fate not tragically intervened 18 months earlier.

As the national team prepared to leave for a tournament in Montevideo, Uruguay in December 1980, Peronace was at a hotel in Rome when he suffered a fatal heart attack, dying in Bearzot’s arms at the age of just 55, leaving a wife and five children. Liam Brady's move to Juventus from Arsenal earlier that year was the last high-profile deal in which he was involved.

|

| The coast around Soverato is famed for an abundance of white, sandy beaches |

Soverato, where Gigi Peronace was born, is situated on the Ionian coast of Calabria, about 37km (23 miles) south of the city of Catanzaro. If the map of Italy is seen as a leg, Soverato is at the point on the underside of the foot at the beginning of the big toe. With a population of fewer than 10,000 and an area of less than eight square kilometres, it is a small town yet thanks to its location on the Gulf of Squillace, notable for its white, sandy beaches, has become the wealthiest town per capita in Calabria with a bright modern promenade, apartment buildings and hotels and a botanical garden established on a reclaimed waste site in 1980. There is little of historical note save for a Pietà sculpted by Antonello Gagini from a block of Carrara marble in 1521, which was recovered from the nearby convent of Santa Maria della Pietà after an earthquake in 1783 and is now kept in the town’s church of Maria Santissima Addolorata.

.jpg) |

| John Charles scoring a goal at a packed Stadio Comunale, which was Juventus's home ground |

Juventus today play at the modern Allianz Stadium, their 41,500-capacity home in the Vallette borough of Turin, about 6km (3.7 miles) northwest from the city centre. When John Charles signed for them in 1957, Juventus shared the Stadio Comunale with city rivals Torino. Situated around four kilometres south of the centre in the Santa Rita district, it was known as the Stadio Municipale Benito Mussolini after it was opened in 1933, being renamed Stadio Comunale after World War II, and further renamed the Stadio Olimpico after being chosen to host the opening and closing ceremonies at the Winter Olympics in 2006. Torino left the stadium with Juventus in 1990 to play at the Stadio delle Alpi, forerunner of the Allianz, but returned to the Olimpico in 2006.

Also on this day:

1463: The birth of antiquities collector Cardinal Andrea della Valle

1466: The birth of banker Agostino Chigi

1797: The birth of opera composer Gaetano Donizetti

1850: The birth of soldier and cardinal Agostino Richelmy