Revolutionary was ideological inspiration for Italian unification

|

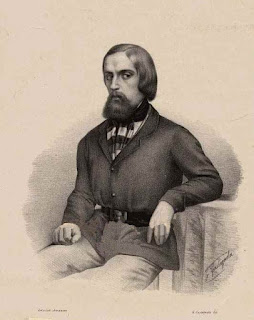

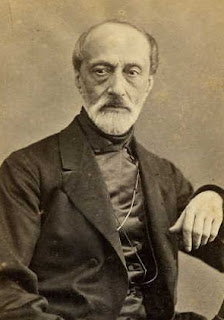

A photographic portrait of

Giuseppe Mazzini |

Giuseppe Mazzini, the journalist and revolutionary who was one of the driving forces behind the Risorgimento, the political and social movement aimed at unifying Italy in the 19th century, died on this day in 1872 in Pisa.

Mazzini is considered to be one of the heroes of the Risorgimento, whose memory is preserved in the names of streets and squares all over Italy.

Where

Giuseppe Garibaldi was the conquering soldier,

Vittorio Emanuele the unifying king and

Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour the statesman who would become Italy's first prime minister,

Mazzini is perhaps best described as the movement's ideological inspiration.

Born in 1807, the son of a university professor in

Genoa, Mazzini spent large parts of his life in exile and some of it in prison. His mission was to free Italy of oppressive foreign powers, to which end he organised numerous uprisings that were invariably crushed. At the time of his death he considered himself to have failed, because the unified Italy was not the democratic republic he had envisaged, but a monarchy.

Yet an estimated 100,000 people turned out for his funeral in

Genoa and he is seen now to have played a vital role in the Risorgimento. His aims were seen by many as noble and just and his commitment to founding and supporting revolutionary groups meant the possibility of violent insurrection would never go away until Italy became one country.

|

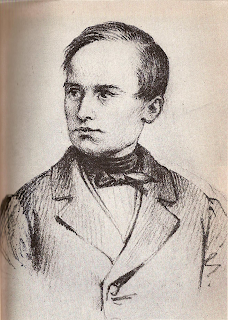

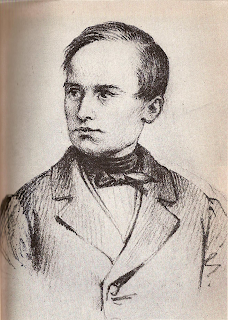

Mazzini as a young man, a drawing

dated at around 1830 |

Intellectually precocious, Mazzini entered university at the age of only 14 and graduated with a law degree before he was 21.

Soon after graduating, he joined a secret political movement known as the

Carbonari, the goal of which was Italian independence through revolution. This led to his arrest in Genoa - then part of the French-controlled Ligurian Republic - and imprisonment. He was released after six months on the condition that he lived in a small hamlet, effectively under house arrest.

Mazzini chose instead to live in exile, first in Switzerland, then in Marseille, where he met

Giuditta Bellerio Sidoli, a beautiful widow originally from Modena, with whom he had a son. He continued his political activity, forming another secret society called

La Giovine Italia (Young Italy), which at its peak had 60,000 members, among them Garibaldi.

Two attempted uprisings in areas of Savoy and Piedmont were put down, with many participants killed. Mazzini was tried in his absence by the authorities in Genoa and sentenced to death but he was undeterred in his ambitions. Moving back to Switzerland, he dreamed not only of a democratic republic uniting Italy but of a unified Europe and encouraged the development of groups similar to Young Italy in Poland and Germany.

Arrested again, he was exiled from Switzerland, returning to Paris to be imprisoned again, securing his release only after promising to move to England, where he lived from January 1837, at several addresses in

London. He continued to plot, his links with revolutionaries in other parts of Europe bringing him to the attention of the British government, who took to intercepting his mail and are thought to have foiled a planned uprising in Bologna by tipping off the occupying Austrians.

|

A plaque commemorates a property in Gower Street, one of

a number of addresses in London where Mazzini lived

|

He returned to Italy to be part of a short-lived Italian government in Rome in 1849 but was forced to retreat to London after the exiled Pope enlisted the support of the French to overthrow the fledgling republic.

Ultimately, the unification process was completed with Mazzini more spectator than participant, the lead role taken by the Savoyan King of Sardinia, Victor Emanuel II, with the support of Garibaldi's

Mille expedition.

The new Kingdom of Italy was created in 1861 under the Savoy monarchy. But Mazzini, although he previously encouraged Victor Emanuel to employ his military resources in the cause of unification, remained fervently republican and refused a seat in the Chamber of Deputies in the new government.

He continued to be politically active and in 1870 tried to start a rebellion in Sicily, following which he was arrested and imprisoned. He was freed after an amnesty was declared.

After more time spent in London, he was in Pisa in Tuscany when he suffered a bout of pleurisy from which he did not recover. The house in which he died in Pisa is now known as Domus Mazziniana and is home to a museum commemorating his life.

|

The house in Genoa in which Mazzini was

born is now a museum.

|

Travel tip:

The house in

Genoa in which Giuseppe Mazzini was born forms part of the Istituto Mazziniano. Together with the archives and historical library, it contains documents and relics related to Mazzini and the Risorgimento, such as signatures, weapons, uniforms and flags. The museum itinerary covers over 120 years of history, including Mazzini's Young Italy movement and Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand. For more information, visit the

museum's own website.

|

| The Mazzini mausoleum at the Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa |

Travel tip:

Mazzini's final house in

Pisa, the Domus Mazziniana, was badly damaged during the bombardment of the city in 1943, with all of the original furniture destroyed. The structure survived, however, and is now open to the public, who can look at a vast library of writings and studies by Giuseppe Mazzini as well as various relics and remains from the Risorgimento. Although he died in Pisa, Mazzini's body was interred in his home town of Genoa. For more information on the museum in Pisa, visit

www.domusmazziniana.it

More reading:

The novel that became a symbol of the Risorgimento

How a Verdi chorus became the Risorgimento's anthem

Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand

Also on this day:

1749: The birth of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's librettist

1900: The birth of architectural sculptor Corrado Parnucci, most famous for his work in the US state of Michigan

Selected books:

A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations

Risorgimento: The History of Italy from Napoleon to Nation State, by Lucy Riall

(Picture credits: Plaque by Edwardx; Mazzini house in Genoa and Mausoleum by Twice25; via Wikimedia Commons)