Risorgimento hero who founded Royal Italian Army

|

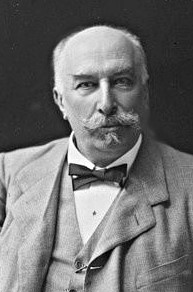

| Manfredo Fanti's battlefield skills were vital to the unification campaign |

Although he ultimately had a disagreement with Giuseppe Garibaldi, the figurehead of the Italian Unification movement, Fanti is still regarded as one of the heroes of the Risorgimento, as a result of the military victories he engineered against the Austrians in the second war of independence, which liberated Lombardy from foreign control, and against the Papal States and the Bourbons in the final push for unification in 1860.

Between the second and third wars of independence, after he had been appointed Minister of War in the Cavour government, Fanti organised the absorption of the army of the League of Central Italy into the Royal Sardinian Army, which he was later able to decree would take the name of the Royal Italian Army.

He also played a key role in freeing Italy from foreign domination and completing unification. As Garibaldi was leading his Expedition of the Thousand in the conquest of Sicily, Fanti led the simultaneous campaign in central Italy, winning significant victories against the armies of the Papal States and in the northern territories of the Bourbon-controlled Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Fanti grew up as a citizen of the Duchy of Modena and, in 1825, was admitted into the Pioneer Corps of the army of Duke Francesco IV d'Este. He studied at the military college in Modena, where he obtained a degree in engineering.

|

| The Battle of Castelfidardo saw Fanti lead one of several key victories |

He then moved to Spain, where he served in the army during a battle for power between the regent, Maria Cristina of Bourbon, and the supporters of Don Carlos, who felt he was the legitimate heir to the late King Ferdinand VII, before returning to Italy in 1848 to fight against the Austrians, who controlled most of northern Italy at the time.

Assisted by French troops, he commanded a Lombard brigade of the Sardinian-Piedmontese Army, distinguishing himself on the battlefield with courage and tactical astuteness to win key victories at Palestro, Magenta, and Solferino in the Second Italian War of Independence, which ended with the Armistice of Villafranca and the return of Lombardy to Italian rule, along with most of the northern Italian states, although the Austrians initially retained control of Venetia.

|

| Fanti supported but later had a disagreement with Garibaldi |

In January 1860 , Camillo Count of Cavour, who returned to his position as prime minister of Sardinia-Piedmont after resigning following the Villafranca armistice, made Fanti his Minister for War and the Navy.

When the Expedition of the Thousand began in May, Fanti was appointed head of the army corps in central Italy. He again was an important figure on the battlefield, playing a significant part in the Battle of Castelfidardo and in the conquest of Perugia, which led to the Piedmontese annexation of Papal State territories in Marche and Umbria.

He then became general of the army and chief of staff of the army in southern Italy, defeating the Bourbons at Mola and organising the successful siege of the fortress at Gaeta.

Fanti's opposition to the admission of 5,000 officers of Garibaldi's volunteers into the new Royal Italian Army, with no loss of rank, was one of the reasons for his resignation from the army and government in June 1861, although the death of Cavour was also a factor.

He agreed to return the following year, taking command of an army corps in Florence, but fell ill soon afterwards. He died in Florence in April 1865 at the age of 59. His body was returned to Carpi, where he is buried in the Cathedral Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta. There is a monument to Fanti in Piazza San Marco in Florence by the sculptor Pio Fedi, erected in 1873.

|

| The Cathedral Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta in Carpi, where Manfredo Fandi is buried |

Carpi, which sits in the Padana plain, the area of flat and fertile land through which the Po river flows, became a wealthy town during the era of industrial development in Italy as a centre for textiles and mechanical engineering. Its historic centre, which features a town hall housed in a former castle, is based around the Renaissance square, the Piazza Martiri, the third largest square in Italy, which is surrounded by historical buildings such as the Palazzo Pio di Savoia, the Cathedral Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, and the Teatro Comunale. The Palazzo Pio di Savoia houses the Museum of the Deportation, dedicated to the victims of the Nazi concentration camps, and the Museum of the City, which displays artworks and artefacts from Carpi’s past. Carpi was a major centre of the Italian Resistance movement in World War Two and there is a memorial at the site of the former Fossoli concentration camp, where thousands of Jews, political prisoners, and resistance fighters were detained and deported.

Stay in Carpi with Booking.com

|

| The monumental sculpture in Castelfidardo that commemorates the 1860 battle |

Castelfidardo, which can be found about 21km (13 miles) south of the port of Ancona in the Marche region, is a charming hill town with a historical significance. It is renowned as the home of the accordion, which was actually patented in Austria in 1829 but underwent substantial redesign in Castelfidardo, where production of the instrument began in the late 19th century with the establishment of a factory opened by Paolo Soprani, who had bought one of the Austrian models after realising its potential. At one time 51,000 accordions were manufactured in the town in a single year, although production declined after World War Two as musical tastes changed. Nonetheless, it is still home to half of the accordion factories in the whole of Italy. There is inevitably an Accordion Museum, while the Monument of the Battle of Castelfidardo is commemorated with a dramatic monumental sculpture in the town’s Parco delle Rimembranze, by the Venetian sculptor Vito Pardo, which depicts in bronze a charge of infantrymen led by a figure on horseback descending from a mountain of white travertine boulders.

Find accommodation in Castelfidardo with Booking.com

More reading:

How the Battle of Solferino led to the founding of the Red Cross

Why Mazzini was the ideological inspiration for Italian unification

The Frenchman who called for Italians to unite as a single people

Also on this day:

1507: The death of Renaissance painter Gentile Bellini

1821: The death in Rome of English poet John Keats

1822: The birth of archaeologist Giovanni Battista de Rossi

1834: The birth of ill-fated Sicilian banker Emanuele Notarbartolo

1910: The birth of painter Corrado Cagli

(Picture credits: Carpi basilica by Attilios; Castelfidardo sculpture by Ermanon; via Wikimedia Commons)

(Painting of Battle of Castelfidardo by Giovanni Gallucci, Palazzo Comunale, Ancona)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)