The genius behind one of the most quintessentially Italian style symbols

|

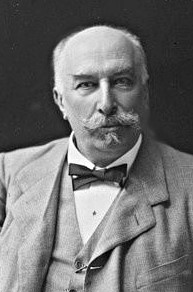

| Alfonso Bialetti (right) pictured in his workshop at his Crusinallo foundry in the 1930s |

Originally designed in 1933, the Moka Express has been a style icon since the 1950s, and it remains a famous symbol of the Italian way of life to this day.

Bialetti was born in 1888 in Montebuglio, a district of the Casale Corte Cerro municipality in Cusio, Piedmont. As a young man, he is said to have alternated between assisting his father, who sold branding irons, and working as an apprentice in small workshops.

He emigrated to France while he was still young and became a foundry worker, acquiring metalworking skills by working for a decade in the French metal industry.

In 1918 he returned to Montebuglio, opened a foundry in nearby Crusinallo and began making metal products. This became the foundation of Alfonso Bialetti & Company.

|

| Moka pots made today have the same design and still carry the L'omino con i baffi logo |

The name given to his invention was inspired by the city of Mokha in Yemen, one of the world’s leading centres for coffee production.

The Moka’s classic design, with its eight-faceted metallic body, is still manufactured by the Bialetti company today and it has become the world’s most famous coffee pot. The use of aluminium was a new idea at the time because it was not a metal that was traditionally used for domestic purposes.

The design transformed the Bialetti company into a leading Italian coffee machine designer and manufacturer.

At the start, Bialetti sold the Moka coffee pot only at local markets, but many millions of Moka coffee pots were to be sold throughout the world during the years to follow. The Moka express was small, cheap to produce, and easy to use, and made it possible for many more people to brew good coffee in their own homes.

When Alfonso Bialetti’s son, Renato, took over the business, he initiated a big marketing campaign to boost the profile of the Moka coffee pot and to ensure the popularity of the Bialetti brand in the face of many copy-cat products coming on to the market.

Key to that campaign was the introduction of a Moka ‘trademark’ on every Bialetti coffee pot in the form of a cartoon caricature - L'omino con i baffi - the little man with the moustache - his right arm raised with finger outstretched as if summoning a waiter, based on a humorous doodle of Renato drawn by Paul Campani, an Italian cartoonist.

Alfonso Bialetti was the grandfather of Alberto Alessi, president of Alessi Spa, the famous Italian design house.

In 2007, Bialetti’s company was listed on the online stock market of the Italian stock exchange.

|

| Montebuglio sits on a hillside a short distance from the picturesque Lago d'Orta |

Montebuglio, where Alfonso Bialetti was born, is a tiny village occupying a hillside location overlooking the valley of the Strona river in Piedmont, a short distance from Lago d’Orta, one of the smaller lakes of the Italian ‘lake district’ but no less picturesque than its better-known neighbour, Lago Maggiore, which lies a few kilometres to the east, the other side of Monte Falò. Montebuglio is a parish of the municipality of Casale Corte Cerro, located 15km (nine miles) from Verbania, 50km (31 miles) from the Swiss town of Locarno and 100km (62 miles) northwest of Milan. The popular Lake Maggiore resorts of Baveno and Stresa are within a short distance of Casale Corte Cerro. The largely wooded countryside around the area is crossed by a dense network of paths, by which walkers are able to reach vantage points on the steep, mountainous slopes from which, in clear weather, it is possible to enjoy a view that includes the Orta, Maggiore, Varese, Monate and Comabbio lakes.

Stay in Casale Corte Cerro with Booking.com

.jpg) |

| Omegna is a beautiful and lively town on the north side of Lake Maggiore's neighbour, Lake Orta |

Omegna, where Bialetti spent the final years of his life and where the Alessi company still has its headquarters, is a lively town on the north side of Lake Orta, an area of outstanding natural beauty where tree-lined mountains meet the shimmering water of the lake. Omegna’s civilisation dates back to the Bronze Age, with settlements subsequently established there by the Ligures - a tribe from Greece - the Celts and Romans. Omegna, which is popular in the summer months, when it hosts many festivals and concerts, is sometimes referred to as the Riviera di San Giulio, named after an early Christian saint buried on an island in Lake Orta. Among places to visit are a museum of the town’s history, the Romanesque church of Sant’Ambrogio and the Porta della Valle, sometimes called Porta Romana, one of five ancient protective gates still standing.

Find accommodation in Omegna with Booking.com

More reading:

The Turin bar and hotel owner who invented the espresso machine

The former peasant farmer who founded the Lavazza coffee company

The opening of Venice’s historic Caffè Florian

Also on March 4:

1678: The birth of composer Antonio Vivaldi

1848: The first Italian Constitution is approved by the King of Sardinia

1916: The birth of writer and novelist Giorgio Bassani

1943: The birth of singer-songwriter Lucio Dalla

(Picture credits: Montebuglio by Bart292CCC; Omegna by Fabio Pocci; via Wikimedia Commons)

.jpg)