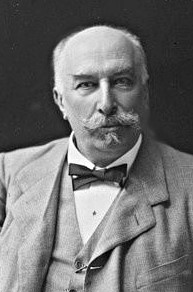

Long-lasting Liberal politician made important social reforms

|

| Giovanni Giolitti was one of Europe's main liberal reformers |

A Liberal, he was the leading statesman in Italy between 1900 and 1914 and was responsible for the introduction of universal male suffrage in the country.

He was considered one of the main liberal reformers of late 19th and early 20th century Europe, along with George Clemenceau, who was twice prime minister of France, and David Lloyd George, who led the British government from 1916 to 1922.

Giolitti is the longest serving democratically-elected prime minister in Italian history and the second longest serving premier after Benito Mussolini. He is considered one of the most important politicians in Italian history.

As a master of the political art of trasformismo, by making a flexible, centrist coalition that isolated the extremes of Left and Right in Italian politics after unification, he developed the national economy, which he saw as essential for producing wealth.

The period between 1901 and 1914, when he was Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior with only brief interruptions, is often referred to as the Giolitti era.

He made progressive social reforms that improved the living standards of ordinary Italians and he nationalised the telephone and railway operators.

Giolitti’s father, Giovenale Giolitti, had worked in the avvocatura dei poveri, assisting poor people in both civil and criminal cases. He died in 1843, the year after his son, Giovanni, was born. The family moved to live in his mother’s family home in Turin, where she taught him to read and write.

|

| Giolitti earned a degree in law from the University of Turin |

His uncle was a friend of Michelangelo Castelli, the secretary of Camillo Benso di Cavour - the united Italy's first prime minister - but Giolitti was not interested in the Risorgimento and did not fight in the Italian Second War of Independence, choosing instead to work in public administration.

At the 1882 Italian general election, Giolitti was elected to the Chamber of Deputies. In 1889 he was selected by Francesco Crispi as the new Minister of Treasury and Finance, but he later resigned because he did not agree with Crispi’s colonial policy.

After the fall of a new government led by Antonio Starabba di Rudini, Giolitti was asked by King Umberto I to form a new cabinet.

He resigned after a series of problems and scandals and was impeached for abuse of power, but this allegation was later quashed. He was once again appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III, but he had to resign in 1905 after losing the support of the Socialists.

When the next prime minister, Sidney Sonnino, lost his majority in 1906, Giolitti became prime minister again. He introduced laws to protect women and child workers and passed a law to provide workers with a weekly day of rest.

Giolitti was re-elected in 1909 but soon had to resign again, afterwards supporting the new head of government, Luigi Luzzatti, while remaining the real power behind the scenes.

In 1911, Luzzati resigned from office and Victor Emmanuel III again gave Giolitti the task of forming a new cabinet.

In 1912, Giolitti got Parliament to approve an electoral reform bill that expanded the electorate from three million to eight and a half million voters. This is thought to have hastened the end of the Giolitti era. The Radicals brought down Giolitti’s coalition in 1914 and he resigned.

He became prime minister again in 1920, supported by Mussolini’s Fascist party, but he had to step down in 1921. By 1925 he had become completely opposed to the Fascist party and refused to join. He died in 1928 in Cavour in Piedmont and his last words to the priest were that he could not sing the official anthem of the Fascist regime.

|

| A section of the Piazza Maggiore, with its frescoed Baroque architecture |

Mondovì is a beautiful town of some 22,000 inhabitants situated in Italy’s Piedmont region at the foot of the southern Alps, close to the border between Piedmont and Liguria. Like much of the area in which it sits, the town is rich in mediaeval frescoes and Baroque architecture from the 17th and 18th centuries, many of the buildings designed by local architect Francesco Gallo. The town is in two sections: the lower town called Breo, which grew up alongside the Ellero river, is linked to the upper town of Piazza by a funicular railway. Mondovì Piazza, the old part of the city founded around 1198, has the two-level Piazza Maggiore at its heart, surrounded by beautiful porticoed buildings such as Palazzo dei Bressani and the Governor’s Palace. Mondovì was one of the most important towns during the Savoy era, with an ancient university and a printing press that produced, in 1472, the first book printed in Piedmont with modern typography. The town’s printing museum - the Museo della Stampa - can be found in the 17th century Palazzo delle Orfane.

.jpg) |

| Cavour is dominated by the giant Rocca di Cavour, which looms over the town |

Cavour is a small town of around 5,500 residents in Piedmont, situated about 40km (25 miles) southeast of Turin, built at the foot of the Rocca di Cavour, an isolated mass of granite rising from otherwise flat terrain. On top of the Rocca, once the site of a Roman village, are some mediaeval remains. The town gave its name to the Benso family of Chieri, of whom the most famous member was Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, the statesman who was a driving force in the Risorgimento and was appointed the first prime minister of the united Italy in 1861. The Rocca di Cavour has been a protected natural park since 1995.

Also on this day:

1782: The birth of virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini

1952: The birth of Oscar-winning actor Roberto Benigni

1962: The death of entrepreneur industrialist Enrico Mattei

1967: The birth of mountaineer Simone Moro