Humanist who lost Greek manuscripts went grey overnight

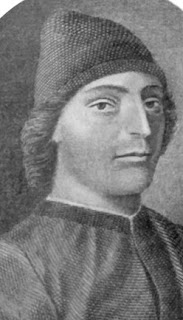

Professor of ancient Greek, Guarino da Verona, who dedicated his life to learning the language and educating others to follow in his footsteps, died on this day in 1460 in Ferrara.Guarino da Verona was a

humanist philosopher

Da Verona studied ancient Greek in Constantinople for more than five years and returned to Italy with two cases full of rare Greek manuscripts that he had collected. It is said that when he lost one of the cases during a shipwreck, he was so distraught that his hair turned grey in a single night.

Da Verona, who was also sometimes known as Guarino Veronese, was born in 1374 in Verona. He studied in Italy and established his first school in the 1390s before going to Constantinople.

After returning to Italy, he earned his living by teaching Greek in Verona, Venice and Florence.

Da Verona taught the philosophy of humanism to Leonello, Marquis of Este, who then became his patron and employed him to teach Greek in Ferrara. Da Verona’s method of teaching became renowned and he attracted students from all over Italy and Europe, even from as far away as England. He supported poor students using his own money and many of them became well known scholars themselves.

He was particularly influenced by the philosopher Georgiu Gemistus Pletho, one of the most famous Greek scholars during the late Byzantine era and a pioneer of reviving Greek scholarship in Western Europe.

|

| Da Verona's Latin grammar Regulae Grammaticales |

He also compiled Regulae Grammaticales, the first Renaissance Latin grammar, which was used well into the 17th century.

The layout of Leonello d’Este’s Studiolo in the Palazzo Belfiore was believed to have been the work of Da Verona. He is also said to have corresponded with the writer and humanist Isotta Nogarola, the first female humanist, who was considered to be one of the most important humanists of the Italian Renaissance and who was also from Verona.

Da Verona died in Ferrara at the age of 86.

Travel tip:The Castello Estense

dominates Ferrara

The city of Ferrara in Emilia-Romagna, about 50km (31 miles) northeast of Bologna, was ruled by the Este family between 1240 and 1598 and is dominated by the magnificent Castello Estense (Este Castle) in the centre of the city began, originally built in 1385 and added to and improved by successive rulers of Ferrara until the Este line ended with the death of Alfonso II d’Este. It was constructed originally as a defensive shield to protect the palace of the Marquis Niccolò II d'Este following a revolt of the Ferrarese population against high taxes at a time when catastrophic floods had left many local people destitute.

Travel tip:A private residence now stands on the site of

the former church of Santa Maria degli Angeli

The Palazzo Belfiore in Ferrara, of which Leonello d'Este's Studiolo was a feature, was destroyed by a fire in 1683, having suffered extensive damage 200 years earlier at the hands of a Venetian army. It is known that it was situated near the Corso Ercole I d'Este, approximately 1km (0.62 miles) north of the Castello Estense. The palace was one of the so-called delizie of the Este dynasty, which were palaces where members of the family could find pleasurable diversions from daily life. These included pursuits that were intellectually stimulating and the Studiolo was a study designed by Da Verona and lined with paintings of the so-called Muses of Greek religion and mythology, nine inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. The nearby church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, also destroyed, once was one of the main burial sites for the Este family. The site of the church is now occupied by a private residence.

Also on this day:

1784: The birth of Princess Maria Antonia of Naples and Sicily

1853: The birth of anarchist Errico Malatesta

1922: The birth of novelist and translator Luciano Bianciardi

1966: The birth of racing driver Fabrizio Giovanardi