Manager led Azzurri to victory in 1934 and 1938

|

| Vittorio Pozzo is Italy's most successful manager |

Under Pozzo's guidance, the Azzurri won the FIFA World Cups of 1934 and 1938 as well as the Olympic football tournament in 1936. He also led them to the Central European International Cup, the forerunner of the European championships, in 1931 and 1935. No other coach in football history has won the World Cup twice.

Pozzo managed some outstanding players, such as Internazionale's Giuseppe Meazza and the Juventus defender Pietro Rava, but his reputation was tarnished by the success of his team coinciding with the Fascist regime's tight grip on power. Italy's success on the football field was exploited ruthlessly as a propaganda vehicle.

While not a Fascist himself, Pozzo upset many opponents of Mussolini across Europe at the 1938 World Cup in France when his players gave the so-called 'Roman' salute - the extended right-arm salute adopted by the Fascists - during the playing of the Italian anthem.

At Italy's opening match against Norway, the salute was greeted with boos and hisses, generated by Italian supporters in the crowd who had fled their home country to escape Fascism. Some of the Italian players dropped their arms but Pozzo ordered them to resume the salute, which further antagonised the crowd.

|

| Pozzo holds aloft the Jules Rimet Trophy surrounded by the Italian team after their 1934 triumph on home soil |

Nonetheless, the incident cast a shadow over the remainder of his career and some commentators feel the appreciation of his achievements was diminished as a result.

Pozzo was born in Turin, where family had moved from the small town of Ponderano in the province of Biella, some 75km (47 miles) north-west of the city in the foothills of the Alps.

He attended the Liceo Cavour, where he studied the classics and languages. He became proficient in English, French and German, in which he expanded his knowledge by studying in England, France and Switzerland.

At the same time, Pozzo took the opportunity to immerse himself in football, for which he had a passion. While in Manchester, he became friends with two prominent players, the Manchester United half-back, Charlie Roberts, and the Derby County forward, Steve Bloomer.

|

| The 1934 World Cup final took place in the Stadio Nazionale del PNF - the national stadium of the Fascist party |

He became involved with the national team for the first time in 1912, when an Italian team - the first in a competitive event - went to the Olympics in Stockholm, but he resigned after defeat to Finland in the first round. He returned to Pirelli before joining the Alpini - the mountain warfare corps of the Italian army - at the outbreak of the First World War.

He was handed the reins of the national team for a second time in 1921. He stepped down again in 1924 following a quarter-final defeat to Switzerland at the Olympics in Paris, although his decision was influenced by the need to care for his wife, who was terminally ill.

Appointed as national team coach for a third time in 1929, he had almost immediate success, winning the Central European International Cup, defeating Hungary 5-0 in the final.

|

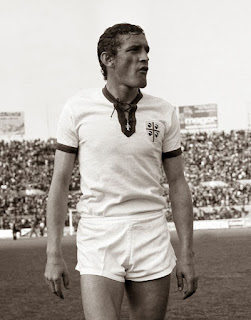

| Giuseppe Meazza of Internazionale was one of Pozzo's key players |

Pozzo saw things differently. His military experiences had taught him that even when on the attack it was an unwise general who would leave his base undefended. Under what he called simply Il Metodo - the Method - he tweaked the 2-3-5 formation, retaining the centre forward and the wingers but pulling the two inside forwards back into midfield, where the half-backs served a dual purpose, supporting the attacking players but dropping back to defend when the opposing team was in possession.

A pragmatist who was always more concerned with winning than entertaining the crowd with expansive football, he was never afraid to leave a player out if his abilities did not suit his tactics. Twice he dropped the team captain, leaving out Adolfo Baloncieri, the Torino star who was country's highest scoring midfield player, in 1930 and, on the eve of 1934 finals, of which Italy were hosts, the Juventus defender Umberto Caligaris.

Thus Pozzo, who became known as il Vecchio Maestro - the Old Master - achieved unprecedented and - so far - unrepeated success.

|

| Pozzo's 2-3-2-3 formation was revolutionary in terms of football tactics |

After declaring his career in management was over, he became a journalist with the Turin newspaper La Stampa, for whom he reported the 1950 World Cup finals.

He returned to his roots in Ponderano on retirement and died there in 1968 at the age of 82, a few months after watching Italy win the 1968 European championships.

Even after his death, some Italians felt his two World Cup wins were devalued by the association with Mussolini's regime. In the 1990s, he was posthumously exonerated, at least in part, when evidence came to light that he had secretly fought with the Italian anti-Fascist resistance during the Second World War.

|

| Biella's Romanesque baptistry in Piazza Duomo |

The village of Ponderano sits just outside Biella, an attractive town in the sub-Alpine area of northern Piedmont. Biella is famed for Menabrea beer, for its production of wool and cashmere products and as a centre for hiking and mountain biking holidays. The Fila sportswear company was founded in Biella in 1911. The town's historic centre is notable for a Romanesque baptistry and the Renaissance church and convent of San Sebastian. Ponderano has staged an annual youth football tournament, one of the most prestigious in Italy, in Pozzo's honour every year since his death.

Turin made its name as Italy’s manufacturing powerhouse, spearheaded by the car giant Fiat, although the city itself has elegant echoes of Paris in the tree-lined boulevards put in place during its time as capital of the Kingdom of Savoy. However, the city's economy suffered badly in the face of global competition in the 1980s, when more than 100,000 workers lost their jobs. Modern Turin is doing its best to regenerate. Former industrial sites such as Parco Dora, once a factory district where Fiat, Michelin and carpet manufacturer Paracchi were big employers, have been transformed into public leisure venues with modern facilities for sport and the infrastructure to host major open-air concerts.

Search Tripadvisor for hotels in Turin

More reading:

Giuseppe Meazza - Italy's first superstar

How Marcello Lippi led Italy to 2006 World Cup glory

Paolo Rossi's hat-trick in World Cup classic

Also on this day:

1603: The birth of the Sicilian painter Pietro Novelli

(Picture credit: Baptistry by Alessandro Vecchi via Wikimedia Commons)

Home