Insurgents took control of city after a major uprising

|

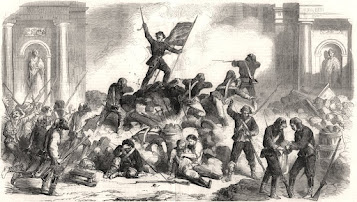

| Sicily had seen previous uprisings in the 19th century, such as this depicted in 1860 during the unification campaign |

The uprising - five years after the island became part of the new Kingdom of Italy - brought to the surface the tensions that existed in southern Italy following the Risorgimento movement and unification.

It was put down harshly by the new government of Italy, who laid siege to the city of Palermo, deploying more than 40,000 soldiers under the command of General Raffaele Cadorna.

It is not known exactly how many Sicilians were killed before the revolt was subdued. Several thousand died as a result of a cholera outbreak that swept through Palermo and the surrounding area, but it is thought that more than 1,000 may have been killed as a direct consequence of the siege.

Sicily did not take well to the imposition of a national government, bringing with it plans to modernise the traditional economy and political system. New laws and taxes and the introduction of compulsory military service caused resentment. There was a feeling also that the industrialisation of Italy was too heavily concentrated in the north, with little investment being made in the south.

Government officials installed in new municipal offices were almost exclusively from the north and many seemed to regard Sicilians almost as barbarians.

|

| General Raffaele Cadorna led the troops who were ordered to crush the revolt |

On the morning of September 16, 1866, however, something much bigger and organised took place, with thousands of people from villages around Palermo gathering at the edge of the city, under the command of some of the island’s disenfranchised former political leaders.

Many were armed, some as the result of storming small government army garrisons. More than 4,000 attacked the prefecture and police headquarters, killing the inspector general of the Public Security Guard Corps.

Similar violence took place in neighbouring towns as word of the Palermo uprising spread, including Monreale, Altofonte and Misilmeri. It is thought that there were possibly as many as 35,000 insurgents in Palermo and its province.

On September 22, seven and a half days after the rioters had begun to mobilise around Palermo, the fighting ceased. The rioters had control of the city and the organised nature of their campaign became clear when a Revolutionary Committee was formed. The secretary was Francesco Bonafede, a follower of the northern revolutionary, Giuseppe Mazzini, and its membership included many figures from the traditional Sicilian aristocracy, including princes, barons and even clergymen, among them the Archbishop of Monreale, Monsignor Benedetto Purchase.

Yet the response of the new national government was uncompromising. On September 27, ships of the Italian Royal Navy bombarded Palermo, destroying the homes of hundreds of citizens, after which the cholera outbreak only accelerated, eventually claiming almost 4,000 victims.

|

| Bandit groups were blamed for stirring up anti-government sentiments |

Army casualties were put at just over 200, along with 42 policemen. The number of insurgents killed is unknown and the estimated figure of 1,000 is probably an under-estimate.

Although this uprising was ultimately quelled, Sicily’s problems did not go away. Outbreaks of less organised violence continued, often blamed on local bandits, and the island’s economic difficulties led to increased emigration, particularly to the United States. Left-wing political groups gained popularity.

Yet Italy’s politicians on the mainland never effectively dealt with the economic imbalance between the north and south and this can be blamed, along with the dismantling of the traditional structures of society, for the growth and influence of organised crime in the shape of the Sicilian Mafia, as well as the Camorra in Naples and its surrounds, the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria and other groups.

|

| Palermo's magnificent Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary |

Although Palermo has long been associated with the Mafia and organised crime, visitors to the city would normally witness nothing to suggest that the criminal underworld has any influence on daily life. The Sicilian capital, on the northern coast of the island, is a vibrant city with a wealth of beautiful architecture bearing testament to a history of northern European and Arabian influences. The church of San Cataldo on Piazza Bellini is a good example of the fusion of Norman and Arabic architectural styles, having a bell tower typical of those common in northern France but with three spherical red domes on the roof, while the city’s majestic Cathedral of the Assumption of Virgin Mary includes Norman, Moorish, Gothic, Baroque and Neoclassical elements. Palermo’s opera house, the Teatro Massimo is the largest in Italy and the third biggest in Europe.

|

| The Cathedral of Santa Maria Nuova at Monreale is described as the finest Norman building in Sicily |

Monreale, which was also the scene of an uprising in 1866, is an historic hill town about 12km (7 miles) west of Palermo. Its Cathedral of Santa Maria Nuova and the adjoining cloisters have been described as the finest Norman buildings in Sicily, its extravagant features in part down to the competition with Palermo to build the island’s greatest cathedral. The buildings have their origin in the 12th century, commissioned by the Norman ruler William II. Mosaic making is still taught in Monreale today, with many workshops around the town. The local cuisine is a mix of traditional Sicilian and cookery of Arab origins.

Also on this day:

1797: The birth of Sir Anthony Panizzi, librarian at the British Museum

1841: The birth of revolutionary politician Alessandro Fortis

2005: The arrest of Camorra boss Paolo di Lauro