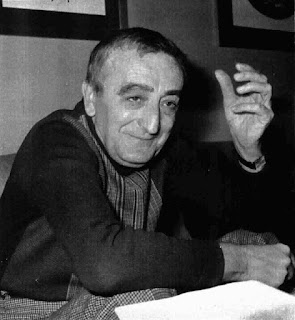

Intellectual whose work sparked argument among Futurists

|

| Photography was only part of Anton Giulio Bragaglia's artistic life |

Bragaglia began his working life in Italy’s nascent movie industry - his father, Francesco, was employed at a studio in Rome - and went on to influence Italy’s cultural life in many more ways as a theatre director, cinematographer and the founder or editor of a number of arts magazines, in addition to his work with photography.

He also founded in 1922 the Teatro Sperimentale degli Independenti, an alternative theatre built by adapting the ancient Roman baths of Septimius Severus in Via degli Avignonesi, a street that runs parallel with the top end of Via del Tritone, near Piazza Barberini.

Francesco Bragaglia, an engineer, was the first technical director of the Cines film studio, which opened in 1906 near Porta San Giovanni in the Italian capital.

Anton Giulio joined the studio as an assistant director in the same year, gaining considerable experience working alongside directors Mario Caserini and Enrico Guazzoni.

When he was 19, however, still to become established as the director, set designer, and cinematographer he would be remembered as, Bragaglia became excited by the fledgling Italian Futurist movement and their enthusiasm for speed, dynamism and technology.

He and his older brothers, Arturo and Carlo Ludovico, both of whom worked, like Anton Giulio, in the film business, wanted to become active participants in the movement, which rejected traditional art and would influence painting, literature, sculpture and architecture in Italy in the early part of the 20th century.

Through their experimental work with cameras, they found ways to capture movement, energy, and continuity in photographs, using long exposures to create blurred forms and the impression of movement.

Anton Giulio set out their methods and vision in his 1911 manifesto, entitled Fotodinamismo futurista. His photodynamic works, such as Waving and The Typist, were widely admired for demonstrating motion as the essence of modern life and through these he hoped to establish photography as a central medium of Futurist experimentation and a tool for expressing the rhythms of modernity.

|

| Bragaglia's The Typist, in which his open shutter technique was able to capture a sense of movement |

This was mainly down to the influence of Umberto Boccioni, the painter and sculptor, who argued that photography was a mechanical medium that merely copied reality, not true creative art, and could undermine the high-art status of Futurist painting.

Boccioni and others felt that Anton Giulio Bragaglia had been presumptuous in publishing his Fotodinamismo futurista manifesto, accusing him of trying to act as a spokesman for the movement without having the permission to do so.

Despite their expulsion in 1913, Anton Giulio Bragaglia continued to contribute to the avant-garde movement, later founding the Casa d'arte Bragaglia in 1918, welcoming Futurist artists and giving them space to exhibit their work.

He continued to experiment with photography, his work being exhibited in Italy and abroad, including the Venice Biennale in 1924 and 1926.

By then Bragaglia had made a broader impression in the arts world. Having become editor-in-chief of the artistic and theatrical periodical L’Artista in 1911, he founded the magazine La Ruoto and the periodical Cronache di Attualità, attracting impressive lists of contributors to both that included Gabriele D'Annunzio, Grazia Deledda, Rudyard Kipling, Luigi Pirandello, Corrado Alvaro, the poet Trilussa and artists Giorgio De Chirico and Fortunato Depero.

|

| A section of the interior of Bragaglia's Teatro Sperimentale |

In 1918 he founded and directed the Casa d'Arte Bragaglia, which he inaugurated with a personal exhibition by the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla. The following year he directed his first play at the Teatro Argentina in Rome.

In 1922 he opened the Teatro Sperimentale degli Indipendenti, which he directed until 1936, having entrusted the architect and artist Virgilio Marchi with the adaptation of the ancient Roman baths. He engaged Balla, Depero and Prampolini to take care of furnishings and decoration, again with a heavy accent on Futurist styles.

The Teatro Sperimentale degli Indipendenti became a point of reference for the Italian avant-garde, although Bragaglia did not close the door on traditional theatrical forms. Although he embraced the innovations of international theatre, he was also keen to promote young Italian playwrights.

An intellectual with a considerable range of interests, he wrote extensively as a critic on cinema, theatre, dance, scenography and stagecraft, often travelling across Europe and to America to host exhibition and conference tours, while still working actively in the theatre, in which he eventually directed more than 50 productions.

He directed for the last time at the Rome Opera House in 1960, staging Pietro Mascagni's Le maschere, an opera written as an homage to Italian comic opera - opera buffa - and the traditions of commedia dell'arte.

Bragaglia died in July 1960 at the age of 70. His funeral and burial took place at the Verano monumental cemetery in Rome, not far from the Sapienza University.

|

| Piglio occupies an elevated position with sweeping views across the Sacco Valley |

Built on a spur of Monte Scalambra, a somewhat isolated mountain located on the border between the Metropolitan City of Rome and the Province of Frosinone, Bragaglia’s birthplace, Piglio, overlooks the Sacco Valley. At the highest point of the small town stands the castle built by the Colonna family just over 1,000 years ago. The Colonnas lost control of the town but regained it in the 14th century and retained control until the early 19th century. With a history that goes back to ancient Roman times, the town’s strategic position has not always been to its advantage. A fierce battle between the Romans and Hannibal’s army in the valley during the Second Punic War, Napoleon’s armies largely burnt it down in the late 18th century and it was bombed by Allied planes in World War Two. Happily, it has been quieter in recent times and Pope John Paul II used to go there for moments of relaxation, a habit which is commemorated in a path laid out in the town, in which significant quotations attributed to him are engraved. Today, Piglio is known as part of the Cesanese DOCG red wine production area, staging a wine festival in October each year.

Stay near Piglio with Expedia

|

| The Palazzo Barberini, built in the 17th century, now houses one of Rome's major art museums |

Bragaglia opened his Teatro Sperimentale degli Independenti within some ancient Roman baths in the district of Rome known as Rione II - Trevi, an area right at the heart of one of Rome’s most visited areas. Naturally, it features the iconic Trevi Fountain, now more than 250 years old, which remains one of the city’s most popular attractions, so much so that the city now charges tourists a €2 euro fee for the privilege of seeing the fountain close up at peak times. Other major sights within the Trevi rione are the Palazzo Barberini, the Baroque palace built for the Barberini family in the 17th century that stands directly off the piazza and houses one of Rome’s major art museums; the Fontana del Tritone, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s 1643 masterpiece which is the centrepiece of Piazza Barberini; and the Fontana delle Api, another Bernini fountain located just off the piazza.The Via Veneto, one of the city’s most famous boulevards thanks to its association with the Dolce Vita era, begins at Piazza Barberini, while the Quirinal Hill area, which includes several historic churches and the Palazzo Quirinale, the official residence of the Italian President, is also nearby.

Find hotels in Rome with Hotels.com

More reading:

Umberto Boccioni, the leading Futurist artist who died tragically young

How Giacomo Balla’s paintings captured movement and speed

Giorgio De Chirico, founder of the scuola metafisica of Italian art

Also on this day:

1791: The birth of architect Louis Visconti

1881: The birth of Futurist painter Carlo Carrà

1917: The birth of film director Giuseppe De Santis

1929: Lateran Treaty gives independence to Vatican

1948: The birth of footballer Carlo Sartori

1995: The birth of singer Gianluca Ginoble

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)