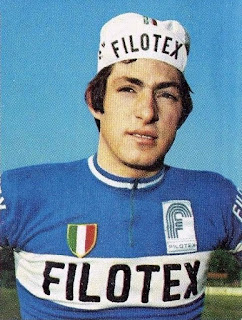

First Italian to win the Tour de France

|

| Bottecchia triumphed despite coming from a poor background |

Bottechia, who took up cycling as a sport only after serving with a cycle battalion of the Bersaglieri Corps in World War One, won the Tours de France of both 1924 and 1925.

Such was his dominance of both those races that he achieved the distinction - unique at the time - of wearing the leader’s yellow jersey for all 15 stages in 1924, a feat he almost repeated the following year, when he held the lead for 13 stages.

His successes brought him fame and financial reward yet his life began in hardship. Born into a poor peasant family, he was named Ottavio for the simple reason that he was the eighth out of nine children. He went to school for only a year before his father insisted he find a job, working first as a shoemaker, then a bricklayer.

His service with the Bersaglieri Corps, an elite, highly-mobile infantry force deployed by the Royal Italian Army, earned him a bronze medal for military valour as a result of what he endured in ferrying messages, supplies and weapons on a folding bicycle across the treacherous Austrian front. He survived malaria, gas attacks, and several spells as a prisoner.

After the war, Bottecchia moved to France to work as a builder but returned to Italy and began racing competitively. Despite having only a borrowed bicycle, he won a number of events and caught the eye of Teodoro Carnielli, a bicycle manufacturer, who gave him the gift of a racing bike and encouraged him to pursue the sport professionally.

Bottecchia’s breakthrough came in 1923 when he placed fifth in the Giro d’Italia, which was considered an extraordinary feat for a rider without a team to support him. Henri Pélissier, a leading French cyclist, invited him to join the Automoto-Hutchinson team, for whom he competed in the Tour de France for the first time, winning a stage and finishing second overall.

|

| A garlanded Bottecchia on his victory lap after his first triumph in the Tour de France, in 1924 |

Nicknamed Il muratore del Friuli - The Bricklayer of Friuli - his victories came to be seen as symbols of perseverance and national pride, his story one of rising from obscurity to dominate the most prestigious race in cycling.

His success enabled him to buy a house in San Martino and open a workshop for the construction of bicycles. He seemed set up for comfortable life.

Yet Bottechia died tragically young, at the age of just 32. In the early summer of 1927, after a relatively lean start to the year in terms of success, he had gone back to the area of Friuli-Venezia Giulia where he had trained previously, hoping it would help him recapture his form.

On June 3 - only 10 days after his brother, Giovanni, had been struck by a car and killed near Conegliano, Veneto - Ottavio was found unconscious by the roadside while training near the Tagliamento river, north of Udine, with a fractured skull, a broken collarbone and other injuries. He died 12 days later in a hospital in Gemona.

There was an assumption that he had lost control of his bicycle and that his death was accidental, yet the bicycle itself was undamaged and there were no signs that he had swerved to avoid a car or been forced off the road.

The uncertainty over the cause of his death gave rise to all manner of theories, including political assassination, given that he was quite outspokenly anti-Fascist in his views. Another story alleged that the farmer who originally claimed to have found Bottecchia by the roadside had actually killed him, albeit accidentally, in trying to stop him stealing grapes from his vines.

Today, Bottecchia’s legacy endures. A museum in his home town commemorates his life, and his name lives on through the Bottecchia bicycle brand, which Carnielli built up after his death. A monument can be found at the roadside where his body was discovered.

|

| The village of San Martino di Colle Umberto, with the church of San Martino Vescovo in the foreground |

San Martino di Colle Umberto, where Bottecchia was born, is a picturesque village in the province of Treviso, north of Venice. Built across two of the hills that form the Colle Umberto, it offers sweeping views of the Prealpi Bellunesi and surrounding countryside, including the town of Vittorio Veneto. The heart of the village is the Chiesa di San Martino Vescovo, a Renaissance-style church dating back to the 15th century which features a striking campanile and a seven-arched portico. During the dominance of the Republic of Venice, San Martino and Colle Umberto became popular retreats for Venetian nobility, drawn to the peaceful hills and scenic beauty. The village is part of the UNESCO-listed Prosecco Hills.

.jpg) |

| A palace in the pretty town of Serravalle |

Vittorio Veneto is a town of some 28,000 people in the province of Treviso, situated between the Piave and Livenza rivers at the foot of the mountain region known as the Prealpi Bellunesi It was formed from the joining of the communities of Serravalle and Ceneda in 1866 and named Vittorio in honour of Victor Emmanuel II. The Veneto suffix was added in 1923 to commemorate the decisive Battle of Vittorio Veneto in 1918, which was a turning point in World War One. The town’s name became a symbol of Italian victory. Ceneda, once a bishopric, and Serravalle, a medieval trading hub, both retain their own character - Serravalle enchants with winding alleys, Renaissance palaces, and the Cathedral of Santa Maria Nova, while Ceneda offers a more ecclesiastical atmosphere with its bishop’s palace and quiet piazzas.

Also on this day:

827: The Arab conquest of Sicily

1464: The death of banker and dynasty founder Cosimo de’ Medici

1776: The birth of soldier Francesca Scanagatta

1831: The birth of baritone Antonio Cotogni

1905: The birth of enameller and painter Paolo De Poli

1964: The birth of actor Kaspar Capparoni