Business launched with socialist newspaper became biggest in Italy

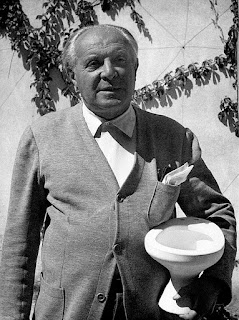

Arnoldo Mondadori (left) pictured with Georges

Simenon, one of the authors of the early gialli

Arnoldo Mondadori, who at the age of 17 founded what would become Italy’s biggest publishing company, was born on this day in 1889 in Poggio Rusco, a small Lombardian town about 40km (25 miles) southeast of Mantua.

As the business grew, Mondadori published Italian editions of works by Winston Churchill, Thomas Mann and Ernest Hemingway among others, as well as by some of Italy’s own literary giants, including Gabriele D’Annunzio and Eugenio Montale.

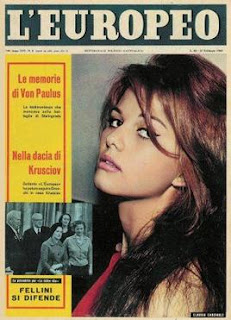

Mondadori was the publisher of news magazines such as Epoca, Tempo and Panorama, launched the women’s magazine, Grazia, struck a deal with Walt Disney to publish children’s magazines, and introduced Italy to detective fiction with a series of crime mysteries called Gialli Mondadori, whose yellow (giallo) covers eventually led to gialli becoming a generic term in the Italian language, used not only to identify a detective novel but to describe unsolved mysteries in real life.

His Oscar Mondadori paperback novels, sold on newsstands, made fiction accessible to much wider audiences than previously, while he set up the Club degli Editori as Italy’s first mail-order book club.

The third of six children born to Domenico Secondo, an itinerant shoemaker, and his wife, Ermenegilda, Arnoldo was forced to give up his formal education at a young age in order to contribute to the family’s income.

|

| The tradition of gialli crime novels was started by Mondadori |

After teaching himself how to operate the machine, he began to publish a socialist newspaper called Luce. He enjoyed his new working environment and with the aid of a benefactor was able to raise enough money to buy the shop and its press.

Mondadori proved to be an astute businessman, soon recognising that handsome profits could be made by producing textbooks for Italy’s growing education system. In 1912 he launched the La Scolastica imprint with Aia Madama, a collection of folk tales assembled by his friend, Tomaso Monicelli, an Ostigliese scholar whose collaboration encouraged other noteworthy authors to sign up with Mondadori.

The outbreak of World War One interrupted the growth of the company, although Mondadori struck on another profitable idea by publishing illustrated newspapers to entertain soldiers on the front line.

After the end of hostilities, the business expanded rapidly, with new partners coming on board, bringing investment and resources that enabled Mondadori to move his headquarters to Milan, open a production centre in Verona and an administrative office in Rome. One such partner, a well-connected Milan industrialist called Senatore Borletti, enabled Mondadori to make valuable contacts inside the increasingly powerful Fascist party, which turned out to be vital when the Fascist government introduced strict controls in the education system.

It was Borletti who helped persuade D’Annunzio, the aristocratic writer, soldier and nationalist politician, to join Mondadori when he retired to his home on Lake Garda to devote his later years to writing poetry and plays.

|

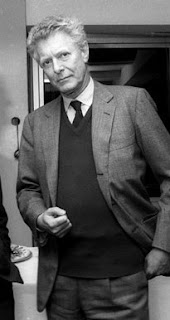

| Arnoldo Mondadori turned his business into Italy's biggest publishing company |

This cosying up to the regime proved to be worthwhile when the decision was made in 1928 to require schools to teach from just one, state-sanctioned textbook. Soon, almost a third of these textbooks were being printed and distributed by Mondadori and in time he had a virtual monopoly.

Nonetheless, this shrinking of the market in school books required Mondadori to establish other business models.

Encouraged by Luigi Rusca, a translator and director of the company, who had seen the success of the genre in the United States, Mondadori moved into publishing crime fiction. At first, it was foreign writers such as Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Georges Simenon, Agatha Christie and Erle Stanley Gardner whose stories began to appear in Italian translation. Yet they were so successful, with 5,000 copies sold in the first month following the launch, that Italian writers began to take an interest in the genre and in 1931 the first truly Italian giallo - Alessandro Varaldo’s Il Sette Bello - was added to the series.

In 1935, the publishing house further diversified through an agreement with Walt Disney to publish children's magazines based on Disney comics characters, a deal which ran until 1988. Grazia magazine launched in 1938.

_07.jpg) |

| The present headquarters of Arnaldo Mondadore Editore at Segrate, an eastern suburb of Milan |

After the war, the business shifted more and more towards magazine publishing, but books remained a large part of Mondadori’s success, particularly the Oscar Mondadori series, which was launched in 1965 with Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. In the same year, the number of people employed by the company, which stood at 335 in 1950, topped 3,000.

Arnoldo Mondadori died in 1971 at the age of 81, after which the control of the business passed to the younger of his two sons, Giorgio, who had been chairman at the time of his father’s death. Arnoldo was survived by his wife, Andreina.

Giorgio commissioned the Mondadori group’s impressive headquarters at Segrate on the outskirts of Milan but left the company in 1976 after his two sisters, Cristina and Mimma, merged their shares to acquire a controlling interest, putting Cristina’s husband, Mario Formenton, in charge.

Since 1991, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore has been controlled by Fininvest, the holding company established by the late Silvio Berlusconi. The former Italian prime minister’s daughter, Marina, has been chair since 2003.

Travel tip:The elegant parish church of Santissimo

Nome di Maria in Poggio Rusco

Poggio Rusco, where Arnoldo Mondadori was born, is a town of around 6,500 inhabitants, to which visitors can experience the authentic culture and cuisine of the Oltrepò Mantovano area. Surrounded by fertile fields and canals, Poggio Rusco has an impressive 16th-century castle, an elegant parish church, and an ancient tower that overlooks the town. Local specialties include tortelli di zucca, the pumpkin-filled pasta, and salame mantovano, a typical cured meat. Poggio Rusco is well placed as a base from which to explore the nearby cities of Mantua, Verona, Ferrara, Bologna and Modena, which are all within an hour's drive.

Travel tip:

The art nouveau Palazzina Mondadori in Ostiglia,

once the home of La Sociale print workshop

Ostiglia, where Mondadori launched his business career in 1907, is a small town located along the ancient Via Claudia Augusta Padana, overlooking the Po River, in a strategic position once exploited by the Romans. The area around Ostiglia, which lies just under 35km (22 miles) southeast of Mantua, is popular with visitors for its network of nature trails, many of them in the Paludi di Ostiglia nature reserve, which is home to 175 bird species. There are also many cycle routes, including one that links Ostiglia with the city of Treviso in Veneto, which follows the path of the disused 120km (75 miles) Treviso-Ostiglia military railway line. The centre of Ostiglia is notable for its mediaeval towers and art nouveau houses, while the archaeological museum tells the town’s history from its days as the Roman trading post, Hostilia. The Roman historian Cornelius Nepote, who was born there, as was Ermanno, Marquis of Verona, who built the town’s castle. Mondadori's first printing house, La Sociale, can be visited as part of the art nouveau Palazzina Mondadori, which today houses Arnoldo Mondadori's personal and private library, consisting of about 1,000 volumes. The building is equipped with classrooms, multimedia and exhibition halls used to promote reading in conjunction with the Fondazione Mondadori.

Also on this day:

293: The death of San Giusto of Trieste

1418: The birth of builder and diarist Gaspare Nadi

1475: The death of condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni

1893: The birth of car designer Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina

1906: The birth of film director Luchino Visconti