Sicilian honoured multiple times for World War One daring

|

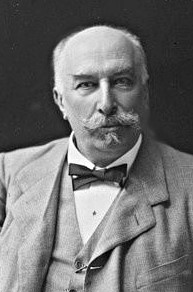

| Luigi Rizzo, bedecked with his array of medals, pictured in 1935 |

Rizzo, who was awarded the title Count of Grado and Premuda in recognition of two of his greatest successes, rose to the rank of Commander in the Royal Italian Navy, later upgraded to honorary Admiral, and won numerous decorations for bravery, including two Gold Medals and four Silver Medals for Military Valour.

Born into a family of merchant ship captains, Rizzo began his maritime career in the merchant navy. His transition to military service came in 1912 when he was appointed second lieutenant in the Naval Reserve.

With Italy’s entry into World War One in 1915, Rizzo was assigned to the maritime defence of Grado, a fashionable Austro-Hungarian seaside resort that had been seized by the Italian army because of its strategic importance in the northern Adriatic.

It had become a base for the Italian navy’s torpedo boats and seaplanes and the courage and tactical acumen displayed by Rizzo in protecting the new base, which made use of its natural harbour, of earned him a Silver Medal of Military Valour.

Rizzo’s reputation rose still further following his transfer to the elite MAS (Motoscafo Armato Silurante) flotilla - small, fast torpedo boats used for stealth attacks. In December 1917, he led a successful raid in the Gulf of Trieste, sinking the Austro-Hungarian battleship SMS Wien. This feat earned him the Gold Medal of Military Valour and marked him as a formidable naval tactician.

His most legendary feat of daring, which brought him a second Gold Medal, occurred on June 10, 1918 off the Dalmatian island of Premuda, more than 200km (124 miles) south of Trieste, now part of Croatia. Commanding one of the MAS torpedo boats, Rizzo launched a surprise attack that sank the Austro-Hungarian dreadnought SMS Szent István, a 21,700-ton battleship.

|

| The Austro-Hungarian battleship Szent István, shortly before it sank off the island of Premuda |

The wreck of the SMS Szent István remains on the seabed eight nautical miles off the coast of Premuda at a depth of 68m (223 ft). In an area of coast popular with diving enthusiasts, the wreck remains an attraction, although it is considered to be too deeply located for recreational divers because of the specialised equipment required.

Rizzo’s other wartime heroics included the capture of two pilots of an Austrian seaplane that had ditched due to a malfunction, and his missions in the defence of the mouth of the Piave, as a result of which he was promoted to Lieutenant. He was decorated with Silver Medals for Military Valour as a result of both.

During the course of the war, Rizzo also earned the Knight’s Cross of the Military Order of Savoy, along with international honours including France’s Croix de Guerre, Britain’s Distinguished Service Order, and the US Navy Distinguished Service Medal.

In 1919, Rizzo joined Gabriele D’Annunzio’s controversial occupation of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia), commanding the so-called Fleet of Carnaro and aiding in the city’s supply efforts.

|

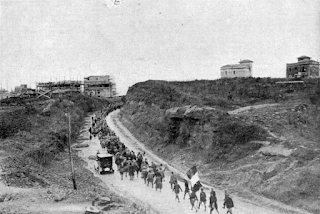

| Rizzo's torpedo boat, safely returned to the lagoon of Venice after sinking the Szent István |

Further recognition followed in 1935 when King Victor Emmanuel III conferred upon Rizzo the victory title Conte di Grado e di Premuda - Count of Grado and Premuda - by royal decree.

When Italy entered World War Two in 1940, Rizzo returned to service and for a while took part in anti-submarine warfare in the Strait of Sicily.

Following the armistice of 1943 and Italy’s surrender to the Allies, Rizzo switched sides and was actively involved in the sabotage of ocean liners and steamships to stop them falling into German hands. He was subsequently arrested by the Nazis and imprisoned in Austria.

He survived the ordeal but suffered personal tragedy in September of that year when his 22-year-old son Giorgio, who had followed him into naval service as a lieutenant in command of an MAS, was killed in a German bombing raid on Piombino.

Rizzo later recovered his son's body from a mass grave on the island of Elba and published a collection of letters and documents in his memory.

Luigi Rizzo died in Rome in 1951 after suffering from lung cancer, despite the efforts of his friend, the surgeon Raffaele Paolucci, whom he had known since they served together as naval commanders in World War One and had gone on to have a distinguished career in surgical medicine.

In addition to Giorgio, Rizzo had two other children, Giacomo and a daughter, Maria Guglielmina, who in 2015 attended the launch near Sestri Levante in Liguria of a Bergamini class frigate built for the Italian Navy and named Luigi Rizzo in his honour.

|

| Milazzo, in northeastern Sicily, is dominated by the huge Norman fortress that watches over it |

Milazzo, where Luigi Rizzo was born, is an historic, coastal town in northeastern Sicily, nestled on a narrow peninsula jutting into the Tyrrhenian Sea. With a population of 31,500, the town has a long tradition of fishing and shipbuilding and is the departure point for ferries to the Aeolian Islands. But it also boasts a mix of sandy and pebbled beaches, with crystal-clear waters ideal for swimming, snorkeling and diving, while the Capo Milazzo, a rugged promontory at the tip of the peninsula, offers dramatic cliffs, hidden cove, and the natural reserve of Piscina di Venere - a tidal pool named after the goddess Venus. A Greek settlement in the 8th century BC, it was later a Roman stronghold and over the centuries has passed through Byzantine, Arab, Norman, and Spanish hands. The town played a key role in several military conflicts, including the Battle of Milazzo in 1860, where Giuseppe Garibaldi’s forces clashed with the Bourbons during Italy’s unification. At the heart of the town stands its massive Norman castle, one of the largest fortified complexes in Sicily.

Stay in Milazzo with Hotels.com

|

| Sunset over the Baia del Silenzio, part of the beautiful Ligurian resort of Sestri Levante |

Sestri Levante, just along the Ligurian coast from the shipyard at Riva Trigoso where the frigate Luigi Rizzo was launched in 2015, is a seaside resort between Genoa and the Cinque Terre, known for its scenic beauty. Part of the town occupies a narrow promontory that divides two stunning bays - the Baia del Silenzio (Bay of Silence), a serene, crescent-shaped beach framed by pastel-colored buildings, and the Baia delle Favole (Bay of Fairy Tales), which was named in honour of the Danish storyteller Hans Christian Andersen, who briefly lived in Sestri Levante. This larger bay hosts the town’s marina as well as promenades, restaurants, and family-friendly beaches. The town celebrates its literary heritage with the annual Andersen Festival, a week-long celebration of storytelling, theatre and music. Sestri Levante’s trattorias and wine bars offer relaxed dining with sea views, featuring local specialities and wines from grapes grown on nearby hills. The resort is popular with Italian families and visitors seeking to enjoy the spectacular beauty of the Ligurian coast without the crowds of Portofino or Monterosso. What’s more, it is easily reached by train, with regular services from Genoa, La Spezia, and Milan.

Find accommodation in Sestri Levante with Expedia

More reading:

How Italy entered World War Two

The WW1 flying ace turned WW2 commander

The Great War hero who became physician to Italy’s Chamber of Deputies

Also on this day:

1551: The birth of composer Giulio Caccini

1881: The birth of Mona Lisa thief Vincenzo Perrugia

1957: The birth of footballer Antonio Cabrini

1965: The birth of chef and TV presenter Carlo Cracco

.jpg)

_-_Exterior.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

_(5904657870).jpg)