Award-winning art expert switched from Fascism to Communism

|

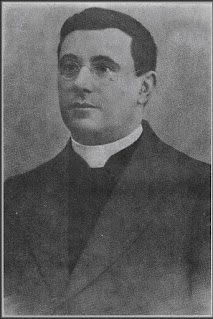

| Giulio Carlo Argan was a major figure in the arts as well as politics |

After stepping down as Mayor of Rome in 1979, Argan represented the Italian Communist Party as a Senator of the Italian Republic, between 1983 and 1992.

Argan’s family were originally from Geneva, but by the 19th century they had settled in the Piedmont region. His father was the bursar of the provincial mental asylum and his mother was a school teacher. After leaving high school, Argan went to study at the University of Turin.

He joined the National Fascist Party in 1928 and after graduating in 1931 worked for the National Arts and Antiquity Directorate. Among his duties were directing the magazine, Le Arti, and helping to establish what became one of the most prestigious institutes for art conservation and restoration.

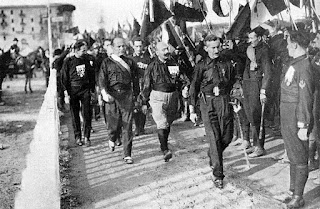

It has been said that his career was helped by his friendship with Cesare Maria De Vecchi, 1st Conte de Val Cismon, one of the four leaders of the Blackshirt mob that marched on Rome in 1922 and helped to put Mussolini in power.

Argan published a manual of art for high schools and contributed to the magazine, Primato, which was run by another high ranking Fascist official. After World War II he taught in the universities of Palermo and Rome.

He co-founded the publishing house, Il Saggiatore, and was a member of the Superior Council of Antiquities and Fine Arts, which was a predecessor to the Ministry of Culture.

|

| Argan became Mayor of Rome in 1976, the first Communist to hold the office |

He then founded an institute for industrial design in Rome In 1973. Argan was interested in art as a form of social engagement, which he thought was integral and necessary to life. He identified architecture and urban planning as areas where the community had a particularly strong interaction with culture.

A prolific writer of books on art, Argan’s major works, which tended to emphasise the social context of art, ranged from studies of Renaissance painters and architects, including Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Michelangelo and Palladio, through the Baroque period in art, to modern sculpture and abstract art. His last book, Michelangelo architetto, was published in 1990.

He stimulated much debate in 1963 with his discussion on ‘the death of art’, by which he meant the end of the creative autonomy of the individual. He saw it as an ‘irreversible’ crisis in the system of traditional art techniques used in an industrial and capitalist society.

He was a professor at the University of Rome from 1959 to 1976. He donated his entire library to the university in 1982, following which he was awarded the title of Professor Emeritus.

In 1976, he was elected as Rome’s first Communist mayor, an office he held for more than three years. While he was Mayor, he supported the defence of the environment and the relaunch of the Imperial Forums, using the slogan: ‘Either cars or monuments,’ and he prevented the construction of a four-star hotel on one of the most panoramic points of the capital city. He resigned as Mayor on health grounds in 1979.

Later, he served as a Communist Senator representing Rome and Tivoli for nearly 11 years.

Argan was awarded the Feltrinelli prize for the Arts in 1958 and the Gold Medal for Merit and Culture in Art by the Italian Republic in 1976.

He died in Rome in 1992, aged 83. After his death, collections of his writing and articles were published.

|

| The site of the Royal Palace was chosen for its open, sunny position |

Giulio Carlo Argan was born in the city of Turin in Piedmont, where much of the architecture illustrates its rich history as the home of the Savoy kings of Italy. In the centre of the city, Piazza Castello, with the Royal Palace, Royal Library, and Palazzo Madama, which used to be where the Italian senate met, showcases some of the finest buildings in ‘royal’ Turin. The Royal Palace – the Palazzo Reale – was built on the site of what had been the Bishop’s Palace, built by Emmanuel Philibert, who was Duke of Savoy from 1528 to 1580. He chose the site because it had an open and sunny position close to other court buildings. Some members of the House of Savoy are buried in Turin’s Duomo in Piazza San Giovanni, which is also famous for being the home of the Turin shroud. Many people believe that the cloth now preserved in the Chapel of the Holy Shroud was the actual burial shroud of Jesus Christ.

|

| The entrance to the Villa d'Este and the Tivoli Gardens, a UNESCO World Heritage site |

Also on this day:

1500: The birth of Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua

1510: The death of painter Sandro Botticelli

1963: The birth of motorcycle world champion Luca Cadalora

1970: The birth of fencing champion Giovanna Trillini

_(5904657870).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)