Scholar has been judged to be the founder of modern science

|

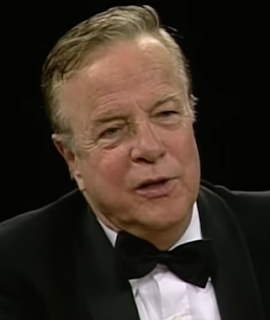

| A portrait of Galileo Galilei painted in 1636 by Justus Sustermans |

His astronomical observations, made with the help of telescopes he designed and engineered himself, confirmed the phases of Venus, discovered the four largest satellites of Jupiter and analysed sunspots. He cannot be credited with inventing the telescope, his own having come later than one patented in Holland, although he was certainly a pioneer of its development. Among Galileo's other inventions, however, the military compass is accepted as solely his.

Controversy marred Galileo's later life. His astronomical observations and other aspects of his scientific knowledge led him to support the view of the Polish scientist Nicolaus Copernicus in the previous century that the sun rather than the earth was the centre of the solar system.

Galileo was educated at a monastery near Florence and considered entering the priesthood but he enrolled instead at the University of Pisa to study medicine.

In 1581 he noticed a swinging chandelier being moved to swing in larger and smaller arcs by air currents. He experimented with two swinging pendulums and found they kept time together although he started one with a large sweep and the other with a smaller sweep. It was almost 100 years before a swinging pendulum was used to create an accurate timepiece.

He talked his father, Vincenzo, a noted lutenist and composer, into letting him study mathematics and natural philosophy instead of medicine and by 1589 had been appointed to the chair of Mathematics at Pisa.

He moved to the University of Padua where he taught geometry, mechanics and astronomy until 1610. His interest in inventing is thought by some historians to have been driven by family circumstances. After the death of their father, Galileo's younger brother, Michelangelo or Michelagnolo, who also became a lutenist and composer, was financially dependent on his older sibling, who saw the invention and patenting of new devices as a way to generate extra income.

Like Galileo Galilei almost two centuries later, Bonaiuti was buried in the Florence's Basilica of Santa Croce, the resting place of many significant historical figures, including the sculptor Michelangelo Buonarotti, the statesman and author Niccolò Machiavelli and the composer Gioachino Rossini.

Following his conviction for heresy and subsequent house arrest, from 1633 until his death at Arcetri in 1642, Galileo wrote one of his finest works, Two New Sciences, about the laws of motion and the principles of mechanics.

Travel tip:

Pisa, the town of Galileo’s birth, is famous the world over for its leaning tower, one of the most popular tourist attractions in Italy . Already tilting when it was completed in 1372, the bell tower of the cathedral is in Piazza del Duomo, also known as Piazza dei Miracoli or Campo dei Miracoli in the centre of Pisa. Pisa's other attractions include a wealth of well-preserved Romanesque buildings, Gothic churches and Renaissance piazzas. The city has a lively charm enhanced by its reputation as a centre of education. The University of Pisa, founded in 1343, now has elite status, rivalling Rome’s Sapienza University as the best in Italy, and a student population of around 50,000 makes for a vibrant cafe and bar scene. Not far from the city is the resort of Marina di Pisa, a seaside town located 12km (7 miles) from Pisa that began to develop in the early 17th century and grew rapidly after a railway line from Pisa opened in 1892. That growth saw the opening of restaurants and hotels and the construction of many beautiful Art Nouveau and neo-medieval villas.

Travel tip:

The Museo Galileo in Florence is in Piazza dei Giudici close to the Uffizi Gallery. It houses one of the biggest collections of scientific instruments in the world in Palazzo Castellani, an 11th century building. The first floor's nine rooms contain the Medici Collections, which include his two extant telescopes and the framed objective lens from the telescope with which he discovered the Galilean moons of Jupiter, plus his thermometers and a collection of terrestrial and celestial globes. The nine rooms on the second floor house instruments and experimental apparatus collected by the 18th-19th century Lorraine dynasty, which bear witness of the remarkable contribution of Tuscany and Italy to the progress of electricity, electromagnetism and chemistry. The museum is open Mondays to Sundays from 9.30 to 18.00, closing at 13.00 on Tuesdays.

This led to his trial and conviction by the Roman Catholic Inquisition as a heretic. He avoided being burned at the stake by reluctantly recanting the statements he had made in a publication on the subject but spent the last 10 years of his life under house arrest at his villa at Arcetri, south of Florence.

Galileo was educated at a monastery near Florence and considered entering the priesthood but he enrolled instead at the University of Pisa to study medicine.

In 1581 he noticed a swinging chandelier being moved to swing in larger and smaller arcs by air currents. He experimented with two swinging pendulums and found they kept time together although he started one with a large sweep and the other with a smaller sweep. It was almost 100 years before a swinging pendulum was used to create an accurate timepiece.

|

| Two of Galileo Galilei's early telescopes, which are kept at the Museo Galileo in Florence |

He moved to the University of Padua where he taught geometry, mechanics and astronomy until 1610. His interest in inventing is thought by some historians to have been driven by family circumstances. After the death of their father, Galileo's younger brother, Michelangelo or Michelagnolo, who also became a lutenist and composer, was financially dependent on his older sibling, who saw the invention and patenting of new devices as a way to generate extra income.

During his own lifetime and subsequently, Galileo tended to be referred to by his first name only, as was common during the 16th and 17th centuries in Italy. He is thought to be related to Galileo Bonaiuti, an important physician, professor, and politician in Florence in the 15th century.

|

| Galileo's appearance before the Inquistion led to him being threatened with being burned at the stake |

Galileo's financial situation might have been better had he not deviated from his father's wish for him to study medicine, which at the time offered a better prospect of a comfortable career. But after his early experiments with pendulums while ostensibly studying medicine, he attended a lecture on geometry and persuaded his father to let him switch to mathematics and natural philosophy. Soon, his inventive mid led to his creation of a thermoscope, a forerunner of the thermometer.

In time Galileo became Chair of Mathematics at Pisa University before moving to the University of Padua, where he taught geometry, mechanics and astronomy and made significant discoveries in both pure science and applied science, for example on the strength of materials and in his advancement of the telescope. He enjoyed the patronage of the Medici and Barberini families at times during his life.

Following his conviction for heresy and subsequent house arrest, from 1633 until his death at Arcetri in 1642, Galileo wrote one of his finest works, Two New Sciences, about the laws of motion and the principles of mechanics.

|

| Pisa's famous leaning tower is unmissable by visitors to the Campo dei Miracoli |

Pisa, the town of Galileo’s birth, is famous the world over for its leaning tower, one of the most popular tourist attractions in Italy . Already tilting when it was completed in 1372, the bell tower of the cathedral is in Piazza del Duomo, also known as Piazza dei Miracoli or Campo dei Miracoli in the centre of Pisa. Pisa's other attractions include a wealth of well-preserved Romanesque buildings, Gothic churches and Renaissance piazzas. The city has a lively charm enhanced by its reputation as a centre of education. The University of Pisa, founded in 1343, now has elite status, rivalling Rome’s Sapienza University as the best in Italy, and a student population of around 50,000 makes for a vibrant cafe and bar scene. Not far from the city is the resort of Marina di Pisa, a seaside town located 12km (7 miles) from Pisa that began to develop in the early 17th century and grew rapidly after a railway line from Pisa opened in 1892. That growth saw the opening of restaurants and hotels and the construction of many beautiful Art Nouveau and neo-medieval villas.

|

| The Museo Galileo in Florence is housed in the 11th century Palazzo Castellani on Piazza dei Giudici |

The Museo Galileo in Florence is in Piazza dei Giudici close to the Uffizi Gallery. It houses one of the biggest collections of scientific instruments in the world in Palazzo Castellani, an 11th century building. The first floor's nine rooms contain the Medici Collections, which include his two extant telescopes and the framed objective lens from the telescope with which he discovered the Galilean moons of Jupiter, plus his thermometers and a collection of terrestrial and celestial globes. The nine rooms on the second floor house instruments and experimental apparatus collected by the 18th-19th century Lorraine dynasty, which bear witness of the remarkable contribution of Tuscany and Italy to the progress of electricity, electromagnetism and chemistry. The museum is open Mondays to Sundays from 9.30 to 18.00, closing at 13.00 on Tuesdays.

More reading:

Galileo Galilei convicted of heresy

Galileo demonstrates the potential of the telescope to Venetian lawmakers

Galileo demonstrates the potential of the telescope to Venetian lawmakers

The disciple of Galileo who invented the barometer

Also on this day:

Also on this day:

(Painting locations: Galileo portrait (1636-40) by Justin Sustermans, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London; Galileo facing the Roman Inquisition (1857) by Cristiano Banti, private collection)