Self-taught artist amassed fortune from his work

|

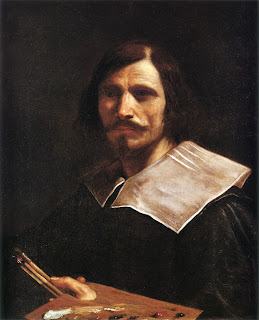

| Guercino - a self-portrait from about 1624-26, which is part of a private collection |

His professional name began as a nickname on account of his squint - guercino means little squinter in Italian. After the death of Guido Reni in 1642, he became established as the leading painter in Bologna.

Guercino painted in the Baroque and classical styles. His best known works include The Arcadian Shepherds (Et in Arcadia Ego - I too am in Arcadia), showing two shepherds who have discovered a skull, which is now on display at the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica in Rome, and The Flaying of Marsyas by Apollo, which can be found in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, both of which were painted in 1618.

The Vatican altarpiece The Burial of Saint Petronilla is considered his masterpiece.

|

| Guercino's Burial of St Petornilla, the Vatican altarpiece |

Mainly self-taught, Guercino became apprenticed at 16 to Benedetto Gennari, a painter of the Bolognese school at his workshop in Cento before moving to Bologna in 1615.

There he made the acquaintance of Ludovico Carracci, whose work was a great influence on him. Carracci encouraged him and Guercino's use of bold colours, and his ability to capture emotion in faces, was an echo of Carracci's style, although some of his early work also bears the stamp of Caravaggio.

As his style developed, Guercino's altarpieces in particular were noted for their depth, achieved by his use of light and darkness. His 1620 altarpiece of the Investiture of Saint William - currently housed at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna - is a great example.

In 1621, Guercino went to Rome, where he was influential in the evolution of Roman High Baroque art. His commissions included the decoration of the Casino Ludovisi, where his outstanding fresco, Aurora, adorns the ceiling of the Grand Hall. It creates the illusion that there is no ceiling, with Aurora’s chariot painted as if it were moving directly over the building.

|

| A detail from the ceiling at the Casino Ludovisi in Rome |

Some critics believe Guercino's move to Rome brought about a subtle change in his style - in the view of some critics, not necessarily for the better - due to the influence of Pope Gregory XV’s private secretary, Monsignor Agucchi, who was a proponent of the classicism of Annibale Carracci, whose work was somewhat more restrained than his cousin, Ludovico.

He is said to have felt under pressure to paint in the popular classical style on his return to Cento two years later, largely because most of his paying clients wanted traditional paintings.

Guercino ran his Cento studio until 1642, when Guido Reni died. Guercino moved to Bologna, taking over Reni's religious picture workshop, and was quickly recognised as the city's leading painter.

|

| Guercino's tomb at the church of Santissimo Salvatore |

As he never married, his estate passed to his nephews and pupils, Benedetto Gennari II and Cesare Gennari. His tomb is in the church of Santissimo Salvatore in Via Cesare Battisti in Bologna.

Travel tip:

The town of Cento, situated in the flatlands of the Po Valley equidistant from Bologna and Ferrara, grew from a fishing village in the marshes to an established farming town in the first few centuries in the second millennium. Previously controlled by the Bishop of Bologna, it was seized by Pope Alexander VI and made part of the dowry of his daughter Lucrezia Borgia. Main sights include the 18th century Palazzo del Monte di Pietà, which houses the Civic Gallery and some paintings by Guercino, whose works can be seen also in the Basilica Collegiata San Biagio, Santa Maria dei Servi, the church of the Rosary, and, in the frazione of Corporeno, the 14th-century church of San Giorgio.

Bologna's Pinacoteca Nazionale can be found in Via delle Belle Arti, a little over a kilometre from Piazza Maggiore to the north-east, inside a former meeting place for young Jesuits in the university district. The Pinacoteca's origins go back to 1762, when paintings from two other collections, one belonging to the Carracci family, were brought together. During the time of Napoleonic rule the most important works were hidden in Paris and Milan. The basis for the current collection was formed in 1827 with a catalogue of 274 paintings. The gallery nowadays consists of 30 exhibition rooms showing works by Bolognese artists from the 14th century onwards, including a number of important canvases by the Carracci brothers, Annibale and Agostino, and their cousin Ludovico. Notable works include Ludovico's Madonna Bargellini, the Comunione di San Girolamo (Communion of St Jerome) by Agostino and the Madonna di San Ludovico by Annibale. There are 15 works by Guercino and 29 by Guido Reni. Also represented in the gallery are Vitale di Bologna, Perugino, Giotto, Raphael, El Greco and Titian.

How mystery still surrounds the death of Caravaggio

Titian - the Venetian giant of Renaissance art

The skill that enabled Giotto to bring figures on canvas to life

1848: Students join uprising in Padua

(Picture credit: Guercino tomb by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons)

More reading:

How mystery still surrounds the death of Caravaggio

Titian - the Venetian giant of Renaissance art

The skill that enabled Giotto to bring figures on canvas to life

Also on this day:

1848: Students join uprising in Padua

(Picture credit: Guercino tomb by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons)