Writer drawn into 18th century Paris rivalry

|

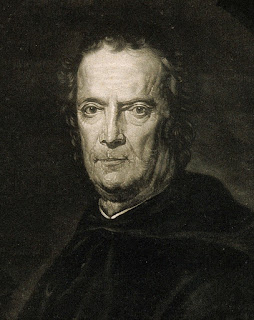

| Niccolò Piccinni was one of Italy's most popular composers in the 18th century |

The composer Niccolò Piccinni, one of the most popular writers

of opera in 18th century Europe, was born on this day in 1728 in

Bari.

Piccinni, who lived mainly in Naples while he was in Italy,

had the misfortune to be placed under house arrest for four years in his 60s, when

he was accused of being a republican revolutionary.

He is primarily remembered, though, for having been invited

to Paris at the height of his popularity to be drawn unwittingly into a battle

between supporters of traditional opera, with its emphasis on catchy melodies

and show-stopping arias, and those of the German composer Christoph Willibald

Gluck, who favoured solemnly serious storytelling more akin to Greek tragedy.

Piccinni’s father was a musician but tried to discourage his

son from following the same career. However, the Bishop of Bari, recognising Niccolò’s

talent, arranged for him to attend the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio in Capuana

in Naples.

He was a prolific writer. His first opera, a comedy entitled

Le donne dispettose (The mischievous women) was staged at the Teatro dei Fiorentini

in Naples in 1755 and after he had formed a working partnership with the acclaimed

librettist Pietro Metastasio his catalogue of works was already well into

double figures when the success of one particular composition won him

popularity across Europe.

La buona figliuola (The good daughter), also known as La

Cecchina, was essentially an opera buffa – a light-hearted comedy – for which

the libretto was written by the famous playwright Carlo Goldoni.

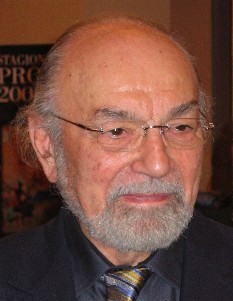

|

| Carlo Goldoni, the Venetian playwright, wrote the libretto for Piccinni's first major success |

It premiered at the Teatro delle Dame in Rome in 1760 and

was so popular it enjoyed a two-year run, acquiring such a reputation as a crowd

pleaser that it was soon attracting packed houses in every capital city in

Europe. What set it apart was that it

was a comedy with dramatic elements and a soft sentimentality designed to touch

the emotions of the audience.

The public enthusiasm for the story was such that a

commercial spin-off industry developed around it almost in the manner of

box-office successes of today, with fashion houses and shops trading on the La

Cecchina name.

The new sentimental style caught on with other composers,

eager to match Piccinni’s success, but at the same time there was a backlash

among conservatives, who felt music, and opera in particular, should be about

strength and manliness and saw this brand of modern Italian music as rather

effete, promoting effeminacy and cowardliness rather than courage and moral virtue.

Among those composers who had their support was Gluck, the

German who had found favour with the Hapsburg court in Vienna. Gluck moved to Paris in the 1770s and when Queen

Marie Antoinette invited Piccinni to live and work in the French capital, the directors

of the Academie Royale de Musique, as the Paris Opera was then known, saw the

commercial potential in pitting the two against one another.

They invited each to compose his own interpretation of the

same texts and deliberately encouraged the Parisian public to fall into one or

the other of two camps – the Gluckists and the Piccinnists. The antagonism between

some factions became quite ugly.

|

| The Piccinni statue in his home city of Bari |

The irony was that Piccinni admired Gluck and while in Paris,

excited by the chance to compose pieces of greater substance, he collaborated

with the celebrated French dramatist Jean-Francois Marmontel on several

projects that he hoped would advance the cause of operatic reform that Gluck

and his intellectual supporters were proposing.

The French Revolution in 1789 – two years after the death of

Gluck - brought to an end Piccinni’s time in Paris and he returned to Naples,

where he was given a warm welcome by King Ferdinand IV, whose wife Maria

Carolina was the ill-fated Marie Antoinette’s sister, only to fall out of

favour when his daughter’s marriage to a French democratic republican brought

him under suspicion of connections and sympathies with the revolutionaries

whose influence Ferdinand feared.

The king’s attitude towards any suspected republicans in

Naples had been uncompromising and many were rounded up and shot. Piccinni was

spared that fate but remained under house arrest for four years.

His fame long since faded, he spent the years after his

release eking out an uncertain living in Naples, Venice and Rome before

returning to Paris in 1798, where he was received with enthusiasm but struggled

to make much money, although with the support of friends he was able to settle

in the comfortable suburb of Passy, where he died in 1800 at the age of 72.

Piccinni’s life is commemorated with a statue in the Piazza della

Prefettura in his home city of Bari in Puglia.

|

| Porta Capuana in Naples used to be part of the city's ancient Aragonese walls |

Travel tip:

Capuana is the area of Naples close to Porta Capuana, a now

free-standing gateway that was once part of the Aragonese walls of the city. Situated roughly between the city’s main

railway station and the Duomo. The

Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio, which was in time absorbed into the Naples

Conservatory, used to be close to the Castel Capuano, originally a 12th-century

fortress which has been modified several times. Until recently, the castle was home to the

city’s Hall of Justice, also known as the Vicaria, comprising legal offices and

a prison.

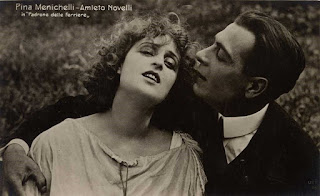

|

| The pretty Via Margutta in Rome, close to where the Teatro delle Dame stood in the 18th and early 19th centuries |

Travel tip:

In the 18th century, Rome’s Teatro delle Dame vied

with the Teatro Capranica for the right to be called the city’s leading opera

house, staging many premieres of works by the leading composers of the day.

Built in 1713 specifically to stage opera seria – as opposed to opera buffa –

and remained a major venue until the early 19th century, when it was

used more often for public dancing, acrobatic shows and plays in local Roman

dialect. Completely destroyed by fire in

1863, it stood where Via Aliberti joins Via Margutta in an area of pretty,

narrow streets close to Piazza di Spagna in the direction of Piazza del Popolo.