‘Man of Honour’ installed as Mayor by Allies

|

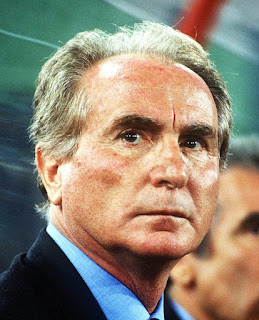

| Calogero Vizzini used his power to solve problems and settle disputes |

He was 76 and had been in declining health. He was in an ambulance that was taking him home from a clinic in Palermo and was just entering the town when he passed away.

His funeral was attended by thousands of peasants dressed in black and a number of politicians as well as priests played active roles in the service. One of his pallbearers was Don Francesco Paolo Bontade, a powerful mafioso from Palermo.

Although he had a criminal past, Don Calò acquired the reputation as an old-fashioned ‘man of honour’, whose position became that of community leader, a man to whom people looked to settle disputes and to maintain order and peace through his power.

In rural Sicily, such figures commanded much greater respect than politicians or policemen, many of whom were corrupt.

In his own words, in a newspaper interview in 1949, his view of the world was that “in every society there has to be a category of people who straighten things out when situations get complicated.

| Like many traditional Mafia figures, Vizzini dressed like a peasant |

His position in this regard was legitimised after the Second World War when the US military government of the occupied territories was looking to ensure the defeated Fascists did not retain any vestige of power on the island.

The Americans wanted positions in a restructured local government on the island to be given to known opponents of Fascism.

Vizzini had once supported Mussolini and had even attended a dinner with the future dictator in Milan in 1922 but turned against him when the Fascists sent Cesare Mori, the so-called Iron Prefect, to Sicily on a mission to destroy the Mafia.

He, and other mafiosi, who would have been almost wiped out but for the Allied invasion, had joined the movement for an independent Sicily and were therefore seen as fitting the bill by the Americans, who installed Vizzini as Mayor of his home town.

For many years, the story has been told that Mafia figures were handed key political positions in return for facilitating the Allied landings but many historians dismiss this as a myth.

|

| A scene from Vizzini's funeral in July 1954 |

Whatever the truth, Don Calò had moved from a life of crime - his ‘charge sheet’ included scores of murders, attempted murders, robberies, thefts and extortions - to one in which local people revered him as a bastion of law and order and a protector of his community.

He had run protection rackets, smuggled livestock, controlled flour mills and sulphur mining, ‘acquired’ considerable land from aristocratic absentee landlords, and operated a huge black market business during the Second World War selling goods stolen from warehouses and army bases.

Yet after his death a notice was pinned on the door of the church where his funeral mass would take place. It read: "Humble with the humble. Great with the great. He showed with words and deeds that his Mafia was not criminal. It stood for respect for the law, defence of all rights, greatness of character: it was love."

|

| The Chiesa Madre di San Giuseppe on the main square in Vizzini's home town of Villalba |

Villalba is a town with a population of a little less than 2,000 in the province of Caltanissetta, about 51km (32 miles) northwest of the town of the same name and 68km (42 miles) inland from Agrigento. The name of the village has has Spanish origins, meaning "the white city" because of town's white houses. Villalba is known for the production of cereals, grapes, vegetables, tomatoes, and lentils. The Sagra del Pomodoro (tomato festival) is held in August each year. Important churches include the Chiesa Madre, built in 1700, and the Chiesa della Concezione, erected in 1795, preserving a statue by artist Filippo Quattrocchi.

|

| The Greek Temple of Concordia is one of the attractions in the Valley of the Temples outside Agrigento |

Agrigento, a city of 55,000 inhabitants on the southern coast of Sicily, is built on the site of an ancient Greek city. It is regularly visited by tourists, largely for the ruins of the Greek city Akragas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site generally known as the Valley of the Temples and, at 1,300 hectares, the largest archaeological site in the world. The site features a series of temples, the most impressive of which is the Temple of Concordia, one of the largest and best preserved Doric temples in the world, with 13 rows of six columns, each 6m (20ft) high, still virtually intact.

More reading:

Cesare Mori - Mussolini's fabled Mafia buster

How Charles 'Lucky' Luciano played a part in the Allied invasion of Sicily

Politics, the Mafia and a Labour Day massacre

Also on this day:

138AD - The death of the Roman emperor Hadrian

1897: The birth of former NATO secretary-general Manlio Brosio

Home