Tailor from Perugia whose Ellesse brand found global success

|

| The Ellesse logo came to symbolise the style and quality associated with the brand's range |

Ellesse - the name is taken from Servadio’s initials as they are spelled in the Italian alphabet, elle and esse - was a groundbreaker in its field, the first manufacturer to display its brand name on the outside of a garment.

Under Leonardo’s management, it grew to become one of the best known names in sportswear, particularly in the worlds of tennis and skiing, and acquired a glamorous image that enabled it to expand successfully into the leisurewear market.

Now owned by the Pentland Group, a British company with a large portfolio of sportswear brands, at its peak Ellesse sponsored tennis stars such as Chris Evert and Boris Becker, the skier Alberto Tomba and the racing driver Alain Prost, as well as the New York Cosmos football team.

Leonardo, whose parents owned a textile business in Perugia, became interested in making clothes as a young man. He learned tailoring skills at the age of 14 so that he could work in the family shop.

|

| The brilliant Chris Evert was one of the tennis greats signed up by Ellesse |

The company grew, taking on more employees and Leonardo’s brother in law, Franco D’Attoma, who would later become president of the city’s football team, joined the company, taking charge of administrative matters to allow Leonardo to focus on design.

Setting his sights first on skiing, which had always been a passion, he produced high quality skiing trousers, to which he added a distinctive touch in the form of a penguin logo attached to the thighs, and the company name on the lower part of the leg, a marketing device that at the time was unique.

He ploughed his profits into acquiring a plot of land to the west of the city at Ellera di Corciano, where he built a modern factory and warehouse, which remains the company headquarters today. It was around this time that the Ellesse name was born and a decision was taken to sponsor the Italian national alpine skiing team, the brand’s profile receiving a massive boost when Gustav Thöni won the giant slalom world cup wearing the Ellesse name and logo.

A new type of ski garment, which was dubbed the jet pant and featured protective knee pads and a flared bottom worn outside the boot, brought the company further success before Leonardo turned his attention to his other major sporting love, tennis.

With individual and tournament sponsorship as its marketing drivers, Ellesse soon became one of the most visible names in tennis. The Italian number one male player, Corrado Barazzutti, was the first to sign a clothing contract, sporting a new logo, the now-familiar red-and-orange symbol, a semi-circle said to represent the top of a tennis ball bisected by two ski tips.

|

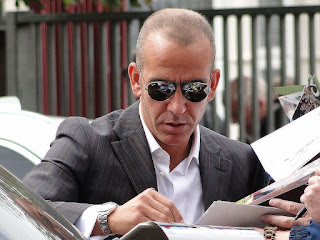

| Leonardo Servadio was often seen at tennis tournaments |

At the time Leonardo sold 90 per cent of the company’s shares to the Pentland Group in 1993, having already struck a deal with Reebok for the sale of Ellesse’s United States operations, the company had annual sales in excess of £80 billion and a workforce of more than 450 employees.

Although he retained an interest in Ellesse as company president, Leonardo devoted much of his time thereafter to projects closer to home.

He turned the large rooms with mediaeval vaults in the city centre that were once home to his father's business into the Caffè di Perugia, which became popular with local people and a great attraction for tourists, including a bar, restaurant and wine shop.

Leonardo Servadio died in Perugia in January 2012 at the age of 87.

Perugia, Leonardo Servadio’s home city and the capital of the Umbria region, is an ancient city that sits on a high hilltop midway between Rome and Florence. In Etruscan times it was one of the most powerful cities of the period. It is also a university town with a long history, the University of Perugia having been founded in 1308. The presence of the University for Foreigners and a number of smaller colleges gives Perugia a student population of more than 40,000. The centre of the city, Piazza IV Novembre, has a mediaeval fountain, the Fontana Maggiore, which was sculpted by Nicolo and Giovanni Pisano. The city’s imposing Basilica di San Domenico, built in the early 14th century also to designs by Giovanni Pisano, is the largest church in Umbria, with a distinctive 60m (197ft) bell tower and a 17th-century interior, designed by Carlo Maderno, lit by enormous stained-glass windows. The basilica contains the tomb of Pope Benedict XI, who died from poisoning in 1304.

Travel tip:.jpg)

A panorama over the skyline of Corciano, the

beautiful town just outside Perugia

Corciano, a beautiful town in Umbria of which Ellera di Corciano is a neighbouring village, can be found about 12km (7 miles) west of the city of Perugia. Surrounded by the mediaeval walls built in the 13th and 14th centuries, it is characterised by small streets and stairways and houses built in limestone and travertine, dominated by the . The village is dominated by a majestic castle, the Rocca Paolina, a monumental fortress built to a design by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger between 1540 and 1543. The town has an imposing gateway, the Porta Santa Maria, while the town's main church, dedicated to Santa Maria Assunta contains an altarpiece painting of the Assumption of the Virgin by Pietro Vannucci, known as il Perugino.

Also on this day:

1451: The birth of composer Franchino Gaffurio

1507: The birth of painter Luca Longhi

1552: The birth of lawyer Alberico Gentili

1883: The birth of fashion designer Nina Ricci

1919: The birth of politician Giulio Andreotti

.jpg)

_-_n._3901_-_Milano_-_Arena_(alternative_take).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.PNG)

.jpg)

.jpg)