Adventurous Roman wrote unique accounts of 17th century Persia and India

|

| Della Valle's journey expanded knowledge of Indian history |

Della Valle was born in Rome into a wealthy and noble family and grew up to study Latin, Greek, classical mythology and the Bible. Another member of his family was Cardinal Andrea della Valle, after whom the Basilica Sant’Andrea della Valle in Rome was named.

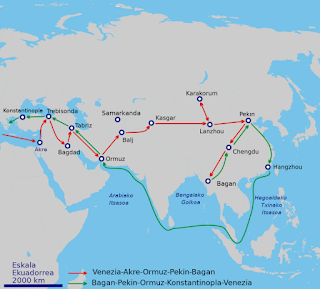

Having been disappointed in love, Pietro Della Valle vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He sailed from Venice to Istanbul, where he lived for more than a year learning Turkish and Arabic.

He then travelled to Jerusalem, by way of Alexandria, Cairo, and Mount Sinai, where he visited the holy sites. He wrote regular letters about his travels to Mario Schipano, a professor of medicine in Naples, who later published them in three volumes.

Della Valle moved on to Damascus, went to Baghdad, where he married a Christian woman, Sitti Maani Gioenida, and then to Persia, now known as Iran. While in the Middle East, Della Valle created one of the first modern records of the location of ancient Babylon.

|

| A 17th century representation of Della Valle's visit to India |

Reaching Surat in north western India in 1623, he was introduced to the king of Kaladi in south India. Della Valle’s memoirs about his experiences provide the best contemporary account of society in that area in the 17th century and are one of the most important sources of history about that period for the region.

The traveller continued southward along the coast to Calicut for the next year and returned to Italy by way of Basra in southern Mesopotamia - now Iraq - and through the desert to Aleppo in Syria, finally reaching Cyprus and then Rome in 1626.

He was appointed a gentleman of the bedchamber - an honorary ceremonial position in the papal court - by Pope Urban VIII to reward him for his exploits.

From his 36 letters to Schipano, which contained more than a million words, three volumes were eventually published: Turkey (1650), Persia (1658) and India (1663). Part of his accounts of his time in India have been translated into English.

Della Valle was also a keen book collector and purchased rare manuscripts while he was in Syria that he brought back to Italy with him.

Once living back in Rome, Della Valle concentrated on music, composing religious music and writing treatises about musical theory, which praised the music of the time countering the criticisms of other contemporary writers. He also wrote libretti for musical spectacles that were performed in Rome.

After his death in 1652, Pietro Della Valle was buried alongside his wife in the family vault in Santa Maria Ara Coeli in Rome.

_-_Facade.jpg) |

| The Basilica of Santa Maria Ara Coeli on the Campidoglio Hill, where Della Valle is buried |

Santa Maria Ara Coeli, the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Altar in Heaven, where Pietro Della Valle is buried in his family’s vault, is on the highest summit of the Campidoglio, one of the seven hills of Rome. It houses relics belonging to Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine. It is claimed the church was built on the site where the Tiburtine Sibyl prophesied the coming of Christ to the Emperor Augustus. In the Middle Ages, condemned criminals used to be publicly executed at the foot of the steps. It is now the designated church of Rome City Council.

_-_2021-08-29_-_2.jpg) |

| The beautiful Basilica of Sant'Andrea della Valle, in the Sant'Eustachio district of Rome |

Travel tip

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea della Valle, named after Cardinal Andrea della Valle, and dedicated to St Andrew the Apostle, is a minor basilica in the rione of Sant’Eustachio in Rome. The dome of the church is the third largest in Rome, behind St Peter’s and the Pantheon. Building work started on the church in 1590 following the designs of Giacomo della Porta and Pier Paolo Olivieri. The church was used as a setting by the composer Puccini for his opera, Tosca.

Also on this day:

1574: The death of Tuscan ruler Cosimo I de’ Medici

1922: The death of castrato singer Alessandro Moreschi

1930: The birth of actress Silvana Mangano

1948: The birth of surgeon and charity founder Gino Strada

.JPG)

_Moschino_LU01112%20(2).jpg)

.jpeg)