Singer who became known as ‘King of the High Cs’

|

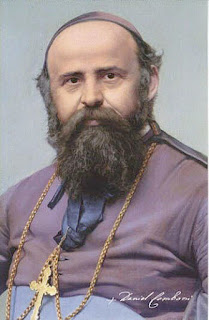

| Luciano Pavarotti |

Pavarotti made many stage appearances and recordings of arias from opera throughout his career. He also crossed over into popular music, gaining fame for the superb quality of his voice.

Towards the end of his career, as one of the legendary Three Tenors, he became known to an even wider audience because of his concerts and television appearances.

Pavarotti began his professional career on stage in Italy in 1961 and gave his final performance, singing the Puccini aria, Nessun Dorma, at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin. He died the following year as a result of pancreatic cancer, aged 71.

The young Pavarotti had dreamt of becoming a goalkeeper for a football team but he later turned his attention to training as a singer.

His earliest influences were his father’s recordings of the Italian tenors, Beniamino Gigli, Tito Schipa and Enrico Caruso. But Pavarotti has said that his own favourite tenor was the Sicilian, Giuseppe di Stefano.

|

| Pavarotti with the Australian soprano Joan Sutherland |

He was later to say that this was the most important experience of his life and had inspired him to become a professional singer.

Pavarotti made his debut as Rodolfo in La Bohème at the Teatro Municipale in Reggio Emilia in 1961.

He sang with Joan Sutherland on a tour of Australia and America and then returned to Italy to make his debut at La Scala in Milan in La Bohème with his childhood friend from Modena, Mirella Freni, singing Mimi opposite his Rodolfo.

His first performance as Tonio in Donizetti’s La fille du regiment took place at the Royal Opera House in London in 1966. This role was later to earn him the title, ‘King of the High Cs’, on account of the aria, Pour mon âme, which requires the singer to deliver the most challenging of notes nine times. Pavarotti, at his peak, was able to hit it every time with no loss of power.

|

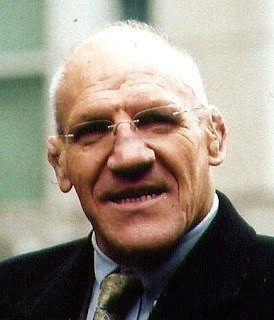

| Pavarotti with Placido Domingo (left) and Jose Carreras at the Three Tenors concert at the Baths of Caracalla in 1990 |

Watch Pavarotti sing Nessun Dorma in Central Park

Every summer he hosted an annual ‘Pavarotti and Friends’ concert in Modena, singing with other popular artists to raise money for humanitarian causes. Having helped to raise money for the elimination of landmines worldwide, he became a close friend of Diana, Princess of Wales, who was also dedicated to the cause. Pavarotti attended her funeral at Westminster Abbey in 1997.

His own funeral was to take place in Modena Cathedral ten years later and, like Princess Diana’s funeral, it was also televised and watched by a huge international audience.

The Vienna State Opera and the Salzburg Festival Hall flew black flags in mourning for the great tenor.

|

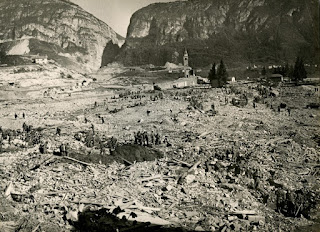

| The Duomo at Modena, where the funeral of Pavarotti took place in 2007 |

Modena is a city on the south side of the Po Valley in the Emilia-Romagna region. The ancient Cathedral of Modena in Piazza Grande, where Pavarotti’s funeral was held, is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its first stone was laid in 1099 but the building was not finished until 1184 and its Gothic Campanile was added in 1319.

Travel tip:

The Baths of Caracalla in Rome, where the first Three Tenors concert was held in 1990, were public baths that had been built in Rome between 211 and 217. They were used free of charge by local people until the sixth century, when the hydraulic installations were destroyed by invaders. During the 1960 Summer Olympics, gymnastic events were hosted there and the Rome Opera company now perform there in the summer. The Baths of Caracalla have become a popular concert venue, following the success of the Three Tenors concert.

More reading:

The genius of Gaetano Donizetti

How Puccini picked up the baton from Verdi

Enrico Caruso - was he the greatest tenor of them all?

How Puccini picked up the baton from Verdi

Enrico Caruso - was he the greatest tenor of them all?

(Top photo of Pavarotti by Pirlouiiiit CC BY-SA 2.0)

Home