Performer inspired by songs of hero Bob Dylan

|

| Francesco de Gregori on stage in 2008 |

The singer-songwriter Francesco De Gregori - popularly known

as "Il Principe dei cantautori" (the prince of the singer-songwriters)

– was born on this day in 1951.

Born in Rome, De Gregori has released around 40 albums in a

career spanning 45 years, selling more than five million records.

Famous for the elegant and often poetic nature of his

lyrics, De Gregori was once described by Bob Dylan as an “Italian folk hero”.

De Gregori acknowledges Dylan as one if his biggest

inspirations and influences, along with Leonard Cohen and the Italian singer

Fabrizio de André. Covers of Dylan songs

have regularly featured in his stage performances. He made an album in 2015 entitled

Love and Theft: De Gregori Sings Bob Dylan.

Born into a middle class family – his father was a librarian,

his mother a teacher - De Gregori spent his youth living in Rome or on the Adriatic coast at Pescara. He began to develop his musical career at the Folkstudio in Rome’s

Trastevere district, where Dylan had performed in 1962.

|

| De Gregori (left) and Lucio Dalla in Genoa in 2010 |

De Gregori's 1973 solo debut album, Alice Non Lo Sa, did not

impress the critics, who were not enthused either by his 1974 follow-up. But

with his 1975 album, Rimmel, he began to enjoy some success. Reviewers liked

his reflective and intelligent lyrics – less obscure than some of his earlier

songs – and the album benefitted from some input from Lucio Dalla, with whom he

struck a lasting friendship.

In 1976 he had another success with Bufalo Bill but an

incident in Milan during a tour the following year led to him abruptly quitting

the music business.

|

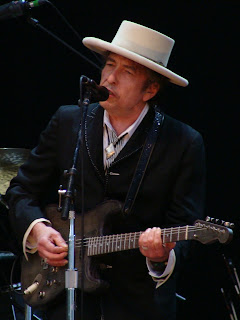

| Bob Dylan in 2010 |

For the next few months he worked as a clerk in a book and

music shop but was persuaded to resume his career the following year. A new

album, De Gregori, included a song, "Generale," that would become one

of his signature tracks. Soon afterwards, he joined Dalla on a successful tour

entitled Banana Republic. The two would

later host a music show on the Rai television network, entitled Due.

Ironically, the title track of his next album, Viva l’Italia,

was adopted as an anthem by the Italian Socialist Party. In 1982 he recorded Titanic, the album many

critics consider his tour de force, and since then, after a period working as a

journalist for the newspaper L’Unità, De Gregori has recorded albums at a rate

of one every year. His latest, Sotto il Vulcano, was released in February this

year.

Married to Alessandra, whom he met at high school, De

Gregori has two sons, Marco and Federico.

His nickname – Il Principe – was given to him by a journalist and apparently

related to his sometimes haughty manner when dealing with the press.

|

| Via Garibaldi in Trastevere |

Travel tip:

The Folkstudio club opened in 1961 in a cellar in Via

Garibaldi in the Trastevere area of Rome. Its founder was an American painter

and musician, Harold Bradley Jr, who invited a then little known Bob Dylan to

play there soon after it opened. The club, which at first promoted jazz and

blues musicians, eventually hosted performers of many different styles and helped

launch the careers of many Italian artists. Bradley moved back to the United States

in 1967 but music lover Giancarlo Cesaroni took over. The club’s premises moved

subsequently to the library L'Uscita, in Via dei Banchi Vecchi, then to Via

Sacchi and later Via Frangipane, near the Colosseum. A plaque on the wall in Via Garibaldi marks

its original home.

De Gregori was raised in the Prati district of Rome, close

to the Vatican and St Peter’s Basilica, which is now an affluent residential neighbourhood

which is popular with tourists for offering a relatively quiet place to stay

that still provides easy access to the city’s historical centre. It has many authentic

Roman trattorie as well as a host of bars and pubs.

The enduring talents of Antonello Venditti

How pop singer Lucio Dalla found inspiration in opera great Enrico Caruso

The story of Adelmo Fornaciari - otherwise known as Zucchero

Also on this day:

1752: The birth of composer Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli

(Picture credits: De Gregori and Dalla by Gianky; Bob Dylan by Alberto Cabello; Via Garibaldi by Mark Ahsmann; Prati street by Lalupa; all via Wikimedia Commons)

Home

More reading:

The enduring talents of Antonello Venditti

How pop singer Lucio Dalla found inspiration in opera great Enrico Caruso

The story of Adelmo Fornaciari - otherwise known as Zucchero

Also on this day:

1752: The birth of composer Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli

1960: The birth of businesswoman Daniela Riccardi

1963: The birth of politician turned TV presenter Irene Pivetti

1963: The birth of politician turned TV presenter Irene Pivetti

(Picture credits: De Gregori and Dalla by Gianky; Bob Dylan by Alberto Cabello; Via Garibaldi by Mark Ahsmann; Prati street by Lalupa; all via Wikimedia Commons)

Home