Italy’s first female prime minister

Politician Giorgia Meloni, who was elected as Italy’s first female prime minister in October 2022, was born on this day in 1977 in Rome._(cropped).jpg)

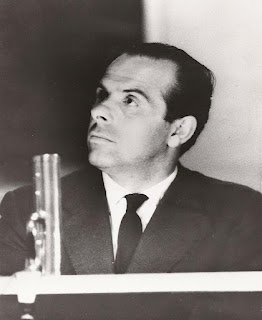

Giorgia Meloni, the first woman to be elected Italy's

PM, on the day she was asked to form a government

Meloni, head of the Fratelli d’Italia party of which she is a co-founder, is a controversial figure in that her political roots are in the Italian Social Movement (MSI), the party formed by supporters of Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini after World War Two. In the past, she has described Mussolini as a “good politician” but one who “made mistakes”.

Yet she rejects accusations that Fratelli d’Italia - Brothers of Italy - is a far-right party, despite adopting the fascist slogan ‘God, family, fatherland’ and incorporating the tricolore flame from the MSI logo within FdI’s own branding.

Meloni came from a fractured family background. Her Sardinian father, Francesco, left her Sicilian mother, Anna, when she was a year old and she and her older sister, Arianna, were brought up largely by her mother in the working class Garbatella area of Rome.

She studied languages at the Istituto Amerigo Vespucci, a high school about 50 minutes across Rome from where she lived, and today describes herself as able to speak Spanish, English and French as well as her native tongue.

|

| A teenaged Meloni unfurls a banner for the Youth Action movement |

As an AN candidate, she was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time in 2006, standing in the Lazio 1 constituency, the boundaries of which correspond to those of the Metropolitan City of Rome.

Re-elected in 2008 on the list of Silvio Berlusconi’s People of Freedom party, which brought together the AN and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, Meloni became the youngest cabinet minister in the history of the Italian Republic when Berlusconi made her Minister for Youth at the age of 31.

Her membership of People of Freedom ended in 2012, however, after a disagreement over the party’s support for technocrat prime minister Mario Monti. With Ignazio LaRussa, Guido Crosetto and others, she formed Fratelli d’Italia, of which she became president in 2014.

Under Meloni’s leadership, Fdl grew from winning just four per cent of the vote at the 2018 general elections to 26 per cent in the snap election of 2022, which made Fratelli d’Italia the biggest single party in the Italian parliament.

Although both Forza Italia and Matteo Salvini’s anti-immigration Lega saw their share of the vote fall, they joined with Fratelli d’Italia in a coalition worth around 44 per cent of votes in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, enough to outvote the centre-left Democratic Party and the populist Five Star Movement even if they were to join forces.

|

| The FdI's logo incorporates the tricolore flame of the MSI |

For example, she is opposed to abortion, euthanasia, same-sex marriage, and LGBT parenting, and supports a naval blockade to stop boats carrying immigrants across the Mediterranean. While committed to NATO, she was generally lukewarm about the European Union until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, after which she distanced herself from previous comments on forging better relations with Vladimir Putin and pledged to keep sending Italian arms to Ukraine.

Meloni’s opponents frequently cite her approval for Mussolini and coalition with Salvini as a warning that Italy may lurch to the right under her premiership, yet Fratelli d’Italia have gone on record as condemning both the suppression of democracy and the introduction of the Italian racial laws by Mussolini’s regime. Meloni herself insists that there is no place for fascist nostalgia in her party and that her own links with it are in the past.

Although not married, Meloni shares a home with Andrea Giambruno, a journalist for TGcom24, a news channel within Berlusconi’s Mediaset group. They have a daughter, Ginevra, who was born in 2016.

Travel tip:

The Art Nouveau design of the Teatro Palladio,

a well-known feature of the Garbatella district

Although traditionally working class, the Garbatella neighbourhood of Rome, where Giorgia Meloni grew up, is becoming increasingly trendy among young Romans, drawn to it having the feeling of a village within the metropolis. Situated in Municipio VIII district south of the city centre near the Ostiense railway station, Garbatella was built in the 1920s, inspired by the English garden city, largely made up of single-family houses grouped around communal garden courtyards. It has some interesting architectural styles, including the Teatro Palladio in Piazza Bartolomeo Romano, an example of Art Nouveau style designed by Innocenzo Sabbatini in 1927. Garbatella today has a population of more than 45,000.

Travel tip:

The Palazzo Monticitorio was chosen as the home

of the Italian Chamber of Deputies in 1871

The Italian Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Italian parliament, sits at the Palazzo Montecitorio, which can be found between the Pantheon and the Spanish Steps. The Palazzo Chigi, official residence of Italian prime ministers, is nearby. Palazzo Montecitorio was originally designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Ludovico Ludovisi, the nephew of Pope Gregory XV. Following Italian unification, the palace was chosen as the seat of the Chamber of Deputies in 1871 but the building proved inadequate for their needs, with poor acoustics and a tendency to become overheated in summer and inhospitably cold in winter. After extensive renovations had been carried out, with many Stile Liberty touches introduced by the architect Ernesto Basile, the chamber returned to the palace in 1918.

Also on this day:

1623: The death of writer and statesman Paolo Sarpi

1926: The death of songwriter and sculptor Giambattista De Curtis

1935: The birth of football coach Gigi Radice

1971: The birth of rugby player Paolo Vaccari

.jpg)

_-_2021-08-29_-_1%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)