Writer used humour and irony in social commentary

|

| Trilussa became known as "the people's poet" |

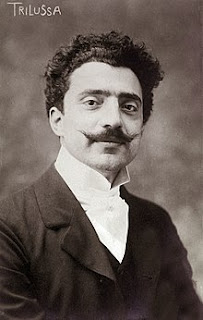

The writer, best known for his works in Romanesco dialect, was actually christened Carlo Alberto Camillo Mariano Salustri. His pseudonym was an anagram of his last name.

He was inspired to take up poetry by his admiration for Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, who satirised life in 19th century Rome in his sonnets, which were also written in Roman dialect.

Born in a house in Via del Babuino, near the Spanish Steps, Carlo was the son of a waiter originally from Albano Laziale in the Castelli Romani area around Lago Albano south of Rome. His mother, Carlotta, was a seamstress born in Bologna.

His early years were marred by tragedy. He lost both a sister and his father before he had reached four years old. After living for a short time in Via Ripetta, close to the Tiber river, his family were offered accommodation in a palazzo in Piazza di Pietra, a square midway between the Pantheon and the Trevi Fountain.

The palazzo was owned by Carlo’s Godfather, the Marquis Ermenegildo del Cinque, who had been introduced to the family by Professor Filippo Chiappini, a disciple of Belli who for a while was Trilussa’s tutor.

Carlo was never a committed student. Twice he was required to repeat a year at high school and left formal education entirely at the age of 15, against the advice of both his mother and Professor Chiappini.

|

| The monument to Trilussa in the square of the same name in Rome |

The following year, he brought together a collection of poems published in Rugantino as a book, called Stelle de Roma: Versi romaneschi (Stars of Rome: Romanesco verses), a series of about 30 madrigals written in appreciation of the most beautiful young women in the city. It sold well.

Soon, Trilussa became a well known name. His work appeared in popular newspapers such as il Mesaggero and il Resto del Carlino.

In 1891, he began a collaboration with Don Chisciotte della Mancia, a newspaper with national circulation, for whom in addition to his poetry he wrote articles commenting on national government as well as life in Rome, ultimately becoming a member of the editorial board.

His second volume of collected verses, Quaranta sonetti romaneschi (Forty Roman Sonnets), which marked the start of a long-running relationship with the publishers, Voghera, included poems he had written for Don Chisciotte della Mancia.

|

| Trilussa was a man of striking appearance who dressed elegantly |

He developed a talent for drawing as well as verse. Some of his published work was accompanied by his own illustrations.

Trilussa managed to avoid running into trouble with the Fascist regime, who generally looked suspiciously at writers and artists, by declaring himself to be not anti-Fascist but non-Fascist. Although he satirised politics even in the turbulent 1920s and ‘30s, his relationship with Mussolini’s government remained relatively uneventful.

A tall man, he always dressed elegantly and lived in an apartment furnished according to his supposedly eclectic tastes, where he entertained fellow artists and writers. He was said to have led a rather hedonistic lifestyle, interspersed with periods of financial difficulty. When he died in December 1950, he had little money.

He never married, yet had a long relationship with Giselda Lombardi - better known as the silent movie actress Leda Gys - who he described as the love of his life. It was Trilussa who launched her career by introducing her to friends in the film business, only for her to meet and marry a producer.

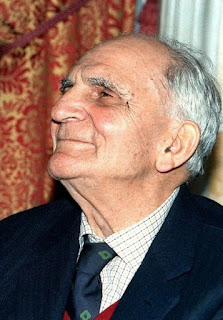

In declining health, he was made a senator for life by President Luigi Einuadi in 1950 but died less than three weeks later. His body is buried at the Verano Cemetery in Rome.

A square in Trastevere, formerly called Piazza Ponte Sisto, was renamed Piazza Trilussa after his death. The beautiful square, surrounded by bars and restaurants, was in an area in which the poet spent much of his time. Nowadays, it is a popular spot with young Romans.

The square features a quirky monument, featuring a bust in bronze leaning over a marble fragment of a Roman ruin, created by the sculptor Lorenzo Ferri in 1954.

|

| The Spanish steps is one of Rome's best known sights |

Trilussa was born in a house not far from the Spanish Steps - known to Romans as the Scalinata di Trinità dei Monti, leading to the piazza and church of the same name at the top of the steps. At the bottom is the Piazza di Spagna, which gets its name from the Spanish Embassy to the Holy See which has been there since the 17th century. The square was popular with English aristocrats on the Grand Tour who stayed there while in Rome. In 1820, the English poet John Keats spent the last few months of his life in a small room overlooking the Spanish Steps and died there of consumption in February 1821, aged just 25. The house is now a museum and library dedicated to the Romantic poets.

|

| The Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere is one of the oldest churches in Rome |

Although formerly a working class neighbourhood, the Trastevere district, which sits alongside the Tiber, is regarded as one of Rome's most charming areas for tourists to visit. Full of winding, cobbled streets and well preserved mediaeval houses, it is fashionable with Rome's young professional class as a place to live, with an abundance of restaurants and bars and a lively student music scene. It is also home to one of the oldest churches in Rome in the Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere, the floor plan and wall structure of which date back to 340AD.

Also on this day:

1685: The birth of composer Domenico Scarlatti

1797: The birth of soprano Giuditta Pasta

1906: The birth of boxer Primo Carnera

1954: Trieste became part of the Italian Republic

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)