Royal theatre reopens quickly after blaze

|

| The damage wreaked by the 1816 fire, captured in a painting by an unknown artist |

The flames spread quickly, destroying a large part of the building in

less than an hour.

The external walls were the only things left standing, but on the orders

of Ferdinand IV, King of Naples, the prestigious theatre was rebuilt at once.

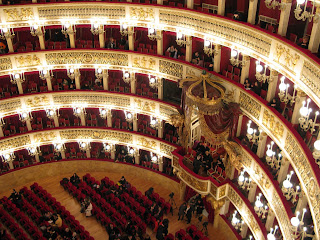

It was reconstructed following designs drawn up by architect Antonio

Niccolini for a horseshoe-shaped auditorium with 1,444 seats. A stunning fresco

was painted in the centre of the ceiling above the auditorium depicting a

classical subject, Apollo presenting to Minerva the greatest poets of the

world.

The rebuilding work took just ten months to complete and the theatre

reopened to the public in January 1817.

Teatro di San Carlo had opened for the first time in 1737, way

ahead of Teatro alla Scala in Milan and La Fenice in Venice.

|

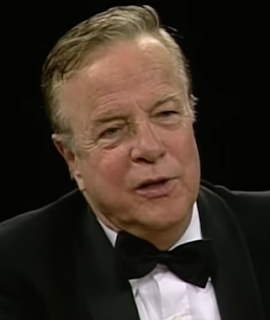

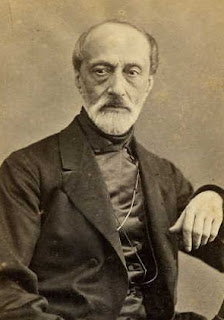

| Gioachino Rossini is among the former artistic directors at San Carlo |

The original theatre was designed by Giovanni Antonio Medrano for the

Bourbon King of Naples, Charles I, and took only eight months to build.

The official inauguration was on the King’s saint’s day, the festival of

San Carlo, on the evening of November 4. There was a performance of Achille in

Sciro by Pietro Metastasio with music by Domenico Sarro, who also conducted the

orchestra for the music for two ballets.

Both Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti served as artistic directors at San

Carlo and the world premieres of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and Rossini’s

Mosè were performed there.

During the Second World War the theatre was damaged by bombs but after

the liberation of Naples in 1943 it was repaired and was able to reopen.

Between 2008 and 2009 a major refurbishment was carried out but the

theatre reopened again to the public in 2010.

In the magnificent auditorium, the focal point is the royal box

surmounted by the crown of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Opera enthusiasts

can take a guided tour of the theatre and see the foyers, the auditorium, the

boxes and the royal box. Tours run at 10.30, 11.30, 12.30, 14.30, 15.30 and

16.30 between Monday and Saturday and at 10.30, 11.30 and 12.30 on Sundays.

Booking is recommended.

Travel Tip:

Close to Teatro di San Carlo in the centre of ‘royal’ Naples, there are

many other sights, such as Galleria Umberto I, Caffè Gambrinus, the church of San Francesco

di Paola and Palazzo Reale, that are all well worth visiting.

More reading:

The 1996 fire that destroyed La Fenice opera house in Venice

How Pietro Metastasio progressed from street entertainer to renowned librettist

Donizetti - the musical genius born in a darkened basement

Also on this day:

More reading:

The 1996 fire that destroyed La Fenice opera house in Venice

How Pietro Metastasio progressed from street entertainer to renowned librettist

Donizetti - the musical genius born in a darkened basement

Also on this day:

(Painting: Rossini portrait by Vincenzo Camuccini, Museo del Teatro alla Scala in Milan)