Won most prestigious awards at Cannes and Venice festivals

|

| Ermanno Olmi's films won some of cinema's most prestigious awards |

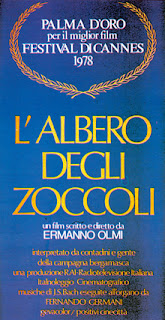

His 1978 film L'albero degli zoccoli - The Tree of Wooden Clogs - a story about Lombard peasant life in the 19th century that had echoes of postwar neorealism in the way it was shot, won the Palme d’Or - one of the most prestigious of film awards - at the Cannes Film Festival of the same year.

A decade later, Olmi won the Golden Lion, the top award at the Venice Film Festival, with La leggenda del santo bevitore - The Legend of the Holy Drinker - a story adapted from a novella by the Austrian author Joseph Roth about a homeless drunk in Paris, who is handed a 200-francs lifeline by a complete stranger and vows to find a way to pay it back as a donation to a local church.

He also won three David di Donatello awards - the Italian equivalent of the Oscars - as Best Director, for Il posto - The Job - his first full length feature film, in 1962, for The Legend of the Holy Drinker, and for Il mestiere delle armi - The Profession of Arms - in 2002.

Born in the Malpensata district of Bergamo, near the railway station, Olmi grew up in Treviglio, a town in Bergamo province about 40km (25 miles) east of Milan. His mother worked in a cotton mill. His father, a railway worker and a staunch anti-Fascist, was killed during World War Two.

As a young man, Olmi enrolled at the Academy of Dramatic Art in Milan to take acting lessons, at the same time taking a job as a messenger at the electric company, Edison-Volta, where his mother also found work.

|

| The original poster for the film seen as Olmi's masterpiece |

Edison-Volta were impressed with Olmi’s work, in particular his 1959 mini-feature film, Il tempo si è fermato - Time Stood Still, a story about a friendship between a student and the guardian of an isolated hydro-electric dam high in the mountains, which he filmed at the Sabbione Dam in Val Formazza, an Alpine valley in Piedmont, close to the Swiss border.

Subsequently, they agreed to support his first full-length feature, Il posto (1961), a semi-autobiographical and gently humorous story about the aspirations of two young men from rural areas whose first jobs are with big firms in Milan in the postwar years. In the tradition of Roberto Rossellini, the neorealist director whom he particularly admired, Olmi cast non-professional actors in many of the roles, one of whom, Loredana Detto, he would later marry.

The success of Il posto, in terms of both critical acclaim and the doors opened by winning a David di Donatello and the critics’ prize at the Venice Film Festival, enabled Olmi to devote himself to film-making. His next few films, including a biographical feature about Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, the Bergamo cardinal who became Pope John XXIII, enjoyed relatively modest success, but in 1978 came the movie regarded by many critics as his masterpiece.

Inspired by the stories he was told by his grandmother about the peasant community in rural Lombardy, L’albero degli zoccoli revolves around the lives of four peasant farming families earning a meagre living on land owned by the same landlord.

.jpg) |

| Olmi followed in the tradition of the neorealist era in using non-professional actors |

As well as winning the Palme d’Or, the movie won critical acclaim in Europe, Britain and the United States, where the actor Al Pacino many years later described it as his favourite film and where the New York Times in 2003 listed The Tree of Wooden Clogs in a feature entitled The Best 1,000 Movies Ever.

Il mestiere delle armi focuses on a battle between a Papal Army led by Giovanni de’ Medici and the army of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, in 1526, highlighting the harsh conditions and ultimate lack of glory in warfare. It was shot in Bulgaria and featured several Bulgarian actors.

In the late 1960s, Olmi and his wife moved to a home he had built at Asiago, in the mountains above Vicenza. It was a story he was told by the residents of Asiago that inspired him to make I recuperanti (The Scavengers), his 1970 film about how the deprivations of World War Two forced local people to dig for scrap metal buried in the ground to sell for cash.

Olmi spent the rest of his life in Asiago, where he died in 2018 after struggling for a number of years with the degenerative neurological condition Guillain-Barré syndrome. Fabio Olmi, one of Ermanno and Loredana's three children, also works in the world of cinema as a director of photography.

.jpg) |

| The Basilica of San Martino in the city of Treviglio |

The small city of Treviglio in Lombardy can be found about 20km (13 miles) south of Bergamo and 40km (25 miles) northeast of Milan, in an area known as Bassa Bergamasca. Treviglio, the second most populous city in Bergamo province with 30,000 inhabitants, developed from a fortified town in the early Middle Ages and, having been at times controlled by the French and the Spanish. It became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. Its most visited attraction is the Basilica of San Martino, originally built in 1008 and reconstructed in 1482, with a Baroque façade from 1740, which is in Piazza Manara. In 1915, the town was chosen by Italy’s future dictator Benito Mussoloni for his civil marriage to the long-suffering Rachele Guidi.

|

| The alpine landscape around the town of Asiago in the northern Veneto region |

Asiago, where Olmi lived from the late 1960s onwards, is in the province of Vicenza in the Veneto, halfway between Vicenza to the south and Trento, the capital of Trentino-Alto-Adige, to the west. It is now a major ski resort and famous for producing Asiago cheese. It is situated on a high plateau known as the Altopiano di Asiago - the Asiago upland - in an area that has been favoured by emigrants from Germany for more than 1,000 years. The widely spoken local dialect, known as Cimbro, is very similar to German. The landscape over the years has been dotted with fortresses. The Interrotto in Camporovere, in the centre of the town, is a barracks-fortress whose construction goes back to the middle of the 1800s. The area also has many reminders of the Battle of Asiago, a major confrontation of Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces in World War One that resulted in more than 25,000 deaths.

Also on this day:

1759: The birth of Victor Emanuel I of Sardinia

1843: The birth of painter Eugene de Blaas

1921: The birth of tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)