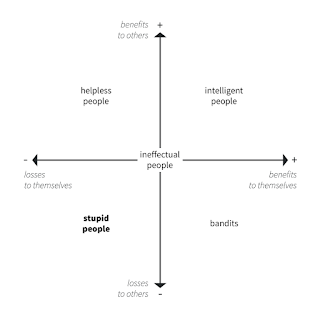

Oil tycoon who rescued AS Roma football club

|

| Franco Sensi was president of AS Roma for 15 years after rescuing the club from financial collapse |

He was 88 and had been in ill health for a number of years. He had been the longest-serving president of the Roma club, remaining at the helm for 15 years, and it is generally accepted that the success the team enjoyed during his tenure - a Serie A title, two Coppa Italia triumphs and two in the Supercoppa Italiana - would not have happened but for his astute management.

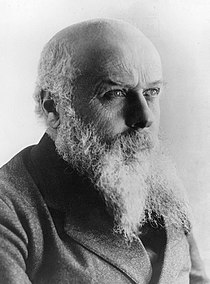

His death was mourned by tens of thousands of Roma fans who filed past his coffin in the days before the funeral at the Basilica of San Lorenzo al Verano, where a crowd put at around 30,000 turned out to witness the funeral procession.

The then-Roma coach Luciano Spalletti and captain Francesco Totti were among the pallbearers.

Sensi, whose father, Silvio, had helped bring about the formation of AS Roma in 1927 in a merger of three other city teams, grew up supporting the club and followed his father into a business career after graduating in mathematics at the University of Messina.

|

| Francesco Totti was among Sensi's pallbearers |

For the next few years he devoted himself to his business career, among other things founding the Italpetroli Company, which would become a major player in the oil and petrochemical sector. He also had interests in publishing and real estate.

At the same time he developed a career in politics, serving as the Christian Democrat mayor of Visso, the small town in the Marche region where his family originated, for 10 years.

Sensi’s return to AS Roma came in 1993 season, when club president Giuseppe Ciarrapico had to step down following his conviction for financial crimes following the bankruptcy of one of his companies.

The club itself was mired in debt and on the brink of collapse. Sensi and his fellow entrepreneur Pietro Mezzaroma stepped in to save the club, Sensi becoming outright owner in November 1994 but then discovering its debts were even greater than he imagined, paying 20 billion lire to own the club but finding that the total owed to creditors was 100 billion lire.

Sensi negotiated a way to stability off the field and then set about rebuilding the team’s fortunes on the field. He hired Carlo Mazzone as coach but though the team finished 7th in Serie A in the 1993-94 season, Sensi wanted better.

Mazzone gave way to Carlo Bianchi and in turn to Zdenek Zeman but success proved elusive until the arrival, in 1999, of Fabio Capello, a proven winner with an impressive coaching CV that included four Serie A titles with AC Milan in the 1990s, and the La Liga championship in Spain with Real Madrid.

| Rosella Sensi took over the running of the club after her father became ill |

Sensi also hired Massimo Neri as a fitness coach, which meant the injury problems that had regularly hampered the team’s progress became much less frequent. Capello set up the team to get the best out of their attacking talent and, with a solid defence marshalled by Samuel, he led Roma to the 2001 Scudetto.

It was not long, unfortunately, before Sensi’s health began to fail him and he handed control of the club to his daughter, Rosella, while continuing to oversee the operation as chairman as Capello’s success continued and returned under Spalletti, who won three trophies in his four years in charge.

Sensi's business achievements were honoured when the President of the Italian Republic made him a Cavaliere del lavoro in 1995 and many Italians believe he should have been appointed head of the Lega Calcio - the Italian Football League.

He is buried in the Verano Cemetery, close to the basilica and to the Sapienza University of Rome in the Tiburtino quarter of Rome.

|

| The village of Visso, in the Sibillini mountains, where Sensi was mayor for 10 years |

The beautiful village of Visso, situated in the national park of the Sibillini mountains, boasts medieval buildings and Renaissance palaces. It is located about 80km (50 miles) southwest of Ancona and about 50km (31 miles) southwest of Macerata. At the heart of the village of the Piazza Pietro Capuzzi, where can be found the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria, which houses a number of medieval works of art. A short distance outside the village is the Sanctuary of Macereto, a Renaissance-style chapel or Marian shrine, built between 1528 and 1538.

|

| The Basilica di San Lorenzo, where Sensi's funeral took place in August 2008 |

The Basilica of San Lorenzo al Verano, also known as the Basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, where Sensi’s funeral was held, is a shrine to the martyred Roman deacon San Lorenzo. An Allied bombing raid in July 1943 devastated the facade, which was subsequently rebuilt. The Basilica is the shrine of the tomb of Saint Lawrence, who was martyred in 258. The Basilica is now known as one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome. It can be found in the Tiburtino quarter, not far from Sapienza University of Rome.

More reading:

The glittering career of Fabio Capello

Marco Delvecchio - the AS Roma striker who became a dance show star

How Angelo Schiavio won Italy's first World Cup

Also on this day:

1498: Cesare Borgia shocks Rome by resigning as a Cardinal

1740: Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini becomes Pope Benedict XIV

Home