Brilliant forward voted Chelsea’s all-time greatest player

|

| Gianfranco Zola scored 58 goals for Chelsea in the Premier League |

Gianfranco Zola, a sublimely talented footballer whose peak

years were spent with Napoli, Parma and Chelsea, was born on this day in 1966

in the Sardinian town of Oliena.

Capped 35 times by the Italian national team, Zola scored

more than 200 goals in his club career, the majority of them playing at the

highest level, including 90 in Italy’s top flight – Serie A – and 58 in the

English Premier League.

He specialised in the spectacular, most of his goals

resulting from his brilliant execution of free kicks or his dazzling ball

control.

Zola went on to be a manager after his playing career ended,

although he has so far been unable to come anywhere near matching his achievements

as a player.

He was probably at his absolute peak during the seven years he spent

playing in England with Chelsea, whose fans named him as the club’s greatest

player of all time in a poll conducted in 2003, shortly before he left to

return to Sardinia.

However, it was probably the four years he spent with

Napoli, his first Serie A club, that were his making as a player, after being

spotted playing club football in Sardinia for Nuorese and Torres.

Zola was signed in 1989 and although his appearances at

first were limited, he developed a close bond with the club’s Argentinian icon,

Diego Maradona, often spending hours alongside him after normal training had

finished, trying to emulate his skills, especially in taking free kicks.

He would later comment that he “learned everything from

Diego.”

|

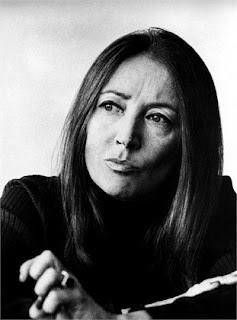

| Zola was hugely popular with Chelsea's fans |

Although he was essentially still a fringe player at that stage, Zola scored two

goals as Napoli won Serie A in 1989-90, giving him his only league winner’s

medal.

When Maradona left under a cloud, having been banned from

playing for drug offences, Zola took his mantle, largely on the maestro’s

recommendation, to which manager Claudio Ranieri responded by giving Zola the

No 10 shirt worn by Maradona.

Napoli were not the force they had been without Maradona,

yet Zola scored 12 goals in the 1991-92 season and another 12 in the 1992-93

campaign, in which he also made 12 assists, giving him the accolade alongside Fiorentina’s

Francesco Baiano of providing the most assists over the Serie A season.

He scored 32 goals in 105 appearances for Napoli, whom he

left in 1993 only because the club, in a difficult financial situation, began

to sell off their best players to pay debts.

Transferred to Parma for 13 billion lire, Zola established

himself as one of the best creative players in Italy alongside Roberto Baggio

and Alessandro del Piero. He scored 18

goals in his first season and 19 in his second campaign as the gialloblù just

missed out on the Serie A title in a hard-fought battle with Juventus.

Favoured by manager Nevio Scala, he was less popular with

Scala’s successor, Carlo Ancelotti, who could not accommodate Zola’s talents in

his 4-4-2 system, leaving the player too often a frustrated figure on the

bench, despite his record of 49 goals in 102 appearances.

News that Zola was unsettled began to circulate and in

November 1996, Chelsea’s then-manager, Ruud Gullit, pulled off what would come

to be regarded as one of the biggest transfer coups in Premier League history,

signing Zola for £4.5 million.

He lit up the Premier League, helping Chelsea win the FA Cup

twice, the League Cup, the Charity Shield, the UEFA Cup-Winners’ Cup and the

UEFA Super Cup. He helped them qualify

for the UEFA Champions League twice as they finished third in the Premier League in

1999 and fourth in 2003, with Zola their leading

goalscorer on each occasion.

|

| Zola, pictured on the touchline as West Ham manager, has not found success as a coach |

His goals were often either big-match winners, such as in

the 1996-97 FA Cup semi-final against Wimbledon or the 1997-98 Cup-Winners’ Cup

final winner, when he scored within seconds of coming off the subs’ bench, or else

works of art, none more celebrated than the mid-air backheel he executed to

score from a corner in an FA Cup tie against Norwich in 2001-02.

Zola scored 16 times in what would be his final season at

Stamford Bridge, having decided he would finish his career back in Sardinia

with the island’s top club, Cagliari. A

week after he gave his word to Cagliari that he would be their player in

2003-04, Roman Abramovich completed his takeover of Chelsea.

The Russian billionaire was desperate to keep Zola at

Stamford Bridge but the Italian told him he would not renege on his

promise. Rumour has it that Abramovich

even considered buying the entire Cagliari club in order to transfer Zola back to

Chelsea.

In the event, Zola kept his promise, helping Cagliari gain

promotion to Serie A in his first season, before retiring at the end of the

2004-05 season, scoring twice against Juventus in his final match.

Capped 35 times by Italy, scoring 10 goals and playing in

the 1994 World Cup finals in the United States, Zola then moved into coaching,

at first as assistant to his friend and former Chelsea teammate Pierluigi

Casiraghi in the Italy Under-21 set-up, then in club football.

However, his management career has so far been dismal

compared with his playing career. He has

managed West Ham, Watford and Birmingham City in England, Cagliari in Italy and

Al-Arabi in Qatar, but has been either sacked or obliged to resign from all

five posts because of poor results.

Married to Franca, Zola has three children. His son, Andrea,

has played for West Ham reserves and for Essex non-League club Grays Athletic.

|

| A church and market in Oliena |

Travel tip:

Oliena, a mountainous town notable for its multi-coloured

rooftops, sits in the shadow of Monte Corrasi, towards the north of the island

of Sardina, about 100km (62 miles) south of Olbia and 200km (124 miles) north

of Cagliari. Probably founded in Roman times, it is famous now for beautiful silk

embroidery and its red wine, Nepente di Oliena.

|

| The waterfront at Cagliari |

Travel tip:

Cagliari is Sardinia’s capital, an industrial centre and one

of the largest ports in the Mediterranean. Yet it is also a city of

considerable beauty and history, most poetically described by the novelist DH

Lawrence when he visited in the 1920s. He set his eyes on the confusion of

domes, palaces and ornamental facades which, he noted, seemed to be piled on

top of one another as he approached from the sea. He compared it to Jerusalem,

describing it as 'strange and rather wonderful, not a bit like Italy.’