Innovative ideas put Italy at the forefront of contemporary style

|

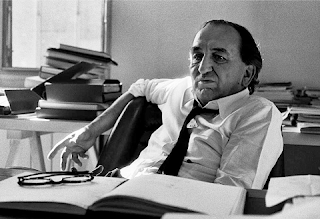

| Marco Zanuso |

Influenced by the Rationalist movement that emerged in the 1920s, he was one of the pioneers of the Modern movement, which brought contemporary styling to mass-produced consumer products. His use of sculptured shapes, bright colours, and modern synthetic materials helped make Italy a leader in furniture fashion.

Italy had for many years been something of a trendsetter in interior design but during the post-War years, with the fall of Fascism and the rise of Socialism, there was a sense of liberation among Italian creative talents.

With the recovery of the Italian economy there was a substantial growth in industrial production and mass-produced furniture. By the 1960s and 1970s, Italian interior design reached its pinnacle of stylishness.

Zanuso was at the forefront, producing designs that used tubular steel, acrylics, latex foam, fibreglass, foam rubber, and injection-moulded plastics.

His first major successes came for Pirelli, the tyre makers, who in 1948 opened a new division, Arflex, to design seating using foam rubber upholstery. They commissioned Zanuso to produce their first designs and his distinctively shaped "Lady" armchair won first prize at the 1951 Milan Triennale.

|

| A folding radio cube designed by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper for Brionvega |

They convinced consumers that plastic could be a viable material for furniture in the home with a brightly coloured, stackable child's chair. Their moulded metal "Lambda" kitchen chair became a worldwide bestseller.

In 1959, Zanuso and Sapper were hired as consultants to Brionvega, an Italian company trying to produce stylish electronics that would challenge those being made in Japan and Germany. They designed a series of radios and televisions that became stylistic icons. Their portable "Doney 14" was the first completely transistorised television.

They also designed a folding "Grillo" telephone for Siemens in 1966, one of the first telephones to put the dial and the earpiece on the same unit.

Zanuso turned his ideas and versatility to other household items, including a bright red fan, bright yellow kitchen scales, a knife sharpener and a streamlined sewing machine.

Several of his award-winning product designs eventually became part of a permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

As an architect, Zanuso also designed housing, factories and offices, not only in Italy but in South America and South Africa.

He designed the Olivetti factory buildings in Buenos Aires in 1954, which featured external air conditioning, another Olivetti building in São Paulo, the Necchi sewing machine company's office building in Pavia in Italy and IBM factory buildings in Milan.

As a member of the city planning commission in Milan, his projects included the renovation of the Teatro Fossati and the construction of the Teatro Strehler, a new venue for the Piccolo Teatro della Città di Milano.

The fifth of six sons of an orthopaedic doctor, he trained in architecture at the Milan Polytechnic university and after military service in the Italian Navy he opened his own design office in 1945 and edited the influential design magazines Domus and Casabella.

He taught architecture and design at the Milan Polytechnic from the 1960s, and served twice as president of the Italian Association of Industrial Design. He continued working into his late 70s, designing a cutlery set for Alessi in 1995.

He died in Milan in 2001, aged 85. His son, Marco Zanuso Jnr, one of four children, followed him into architecture and design.

|

| Zanuso's Piccolo Teatro Strehler in Milan |

The Piccolo Teatro della Città di Milano, founded in 1947, was Italy's first permanent repertory company. It has three venues, the Teatro Grassi, in Via Rovello, between Sforza Castle and the Piazza del Duomo, the Teatro Studio and the Teatro Strehler. The company puts on around 30 performances per year, while the venues host cultural events, including festivals, films, concerts, conferences and conventions.

Travel tip:

The Medieval city of Pavia, once the most important town in northern Italy, has many fine churches, including a cathedral boasting one of the largest domes in Italy and the beautiful Romanesque Basilica di San Michele. The Visconti Castle, surrounded by a large moat, houses the Civic Museum. Another notable attraction is the covered bridge across the Ticino River, a reproduction of a 13th-century bridge destroyed during the Second World War.

(Photo of Zanuso radio by Andrea Pavanello CC BY-SA 3.0)

(Photo of Piccolo Teatro Strehler by Dispe CC BY-SA 3.0)

Home