Poet pursues romantic dream in the Romagna

|

| Lord Byron pursued romance and adventure during his time in Ravenna |

He had risked his own life and liberty two days before by allowing a supply of weapons belonging to the revolutionaries to be housed in his apartment in Palazzo Guiccioli, having been recruited to the Carbonari by Ruggiero and Pietro Gamba, the father and brother of his lover, Teresa Guiccioli.

The Carbonari - literally, the charcoal burners - were a network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy between 1800 and 1831, dedicated to overthrowing oppressive regimes, promoting liberal ideas, and establishing constitutional government. In the run up to Italian unification, the Carbonari fought against foreign domination and absolute monarchy, and were particularly active in southern Italy. Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, two of the main drivers of the Risorgimento movement, were both members.

Byron had joined the Carbonari in 1820, driven by a combination of his own romantic idealism and political convictions and his friendship with the Gamba family in Ravenna.

Byron had been a successful poet and a celebrity back in Regency England, but it had all turned sour because of his unconventional lifestyle, the slurs on his reputation that had been made by a spurned mistress, and the gossip sparked by his close relationship with his half-sister Augusta, after his brief marriage to Annabella Milbanke had ended in separation.

Fleeing from his notoriety, threats to his life, and his financial problems, Byron travelled to Italy in 1816 and settled in Venice.

With his friend, John Cam Hobhouse, he put up at the Hotel Grande Bretagne on the Grand Canal and embarked on a few days of tourism. But it was not long before Byron decided to stay for longer and moved into an apartment just off the Frezzeria, settling in to enjoy life in the city that was to be his home for the next three years.

While living in Venice, he had plenty of romantic liaisons, but his life changed when he met Teresa Guiccioli, the young, beautiful wife of Count Alessandro Guiccioli, who he was introduced to at a social gathering in Venice.

|

| Contessa Teresa Guiccioli, who became Lord Byron's lover |

In due course, Teresa became officially separated from her husband and moved back to live with her father, Ruggiero Gamba, while Byron remained in his apartment in the Count’s palazzo.

On 16 February 1821, Byron wrote in the diary he had started to keep in Ravenna: ‘Last night il Conte (Teresa’s brother, Pietro Gamba) sent a man with a bag full of bayonets, some muskets and some hundred of cartridges to my house.’

These were weapons the Carbonari had asked him to purchase for them but, having had to postpone their plans for an uprising against their Austrian rulers, they had foisted them on to Byron because of the fear the Austrians would discover them and take reprisals against them and they thought he would be less at risk because he was English.

However, because of the climate at the time, If Byron had been found to be housing the weapons he would have been arrested and almost certainly imprisoned, or expelled from Austrian controlled territory.

|

| Both Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi were Carbonari members |

Despite the excitement of secret meetings in the pine forests outside Ravenna with other members of the Carbonari, Byron never got the chance to take part in a revolt against Austrian rule.

Later that year, Teresa’s father, and her brother, were expelled from all papal domains and they had to leave to go and live in Florence, where they would be safe, taking Teresa with them. Byron reluctantly gave up his quarters in Palazzo Guiccioli and followed them a couple of months later.

But within two years, Byron had left Italy to pursue the romantic dream of fighting in the Greek War of Independence. He was to die of a fever in Missolonghi in 1824.

.jpg) |

| Ravenna is the home of the tomb of Dante |

Ravenna in Emilia-Romagna, where Byron lived for two of his six years in Italy, was the capital city of the western Roman empire in the fifth century. It is known for its well-preserved late Roman and Byzantine architecture and has eight UNESCO world heritage sites. The Basilica of San Vitale is one of the most important examples of early Christian Byzantine art and architecture in Europe. Ravenna also houses the tomb of the poet Dante Alighieri, who lived and died there after he was exiled from Florence. Byron was said to have found the tomb of the poet inspirational and would regularly visit it and sit writing his poetry close by it. Florence has repeatedly asked for Dante’s remains to be sent back to them but Ravenna has always refused to relinquish them.

Stay in Ravenna with Hotels.com

|

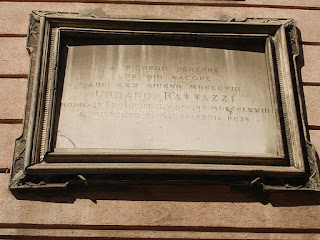

| Palazzo Guiccioli in Ravenna now houses a museum dedicated to Byron |

The first floor (mezzanine) of Palazzo Guiccioli in Via Cavour, where Byron had an apartment during his time in Ravenna, is now a museum dedicated to him. Precious pictures and memorabilia belonging to the poet that were kept by Teresa Guiccioli for the rest of her life are now displayed there and the exhibition is accompanied by text and images telling the story of Byron’s time in Ravenna. The second floor, piano nobile, is occupied by a museum devoted to the Risorgimento. There is a restaurant in the former wine cellar of the palazzo and a bar and souvenir shop can be accessed from the courtyard garden. Palazzo Guiccioli is open to visitors between 10 am and 6 pm from Tuesday to Sunday. For more information visit www.museibyronedelrisorgimento.it.

Search for accommodation in Ravenna with Expedia

More reading:

Shelley dies in dramatic storm

Why Dante remains exiled in Ravenna

Also on this day:

1455: The death of painter Fra Angelico

1564: The death of painter and sculptor Michelangelo

1626: The birth of biologist Francesco Redi

1953: The death of crime writer and playwright Alessandro Varaldo

1967: The birth of footballer Roberto Baggio

1983: The birth of tennis champion Roberta Vinci

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_Exterior.jpg)